What is Shakespeare for?

The question rattled around in my imagination last week as I was teaching for the first time Carlyle Brown’s 1989 play, “The African Company Presents Richard III.” Watching the play with students on Friday night at the Queens Theater intensified the conundrum. What is Shakespeare anyway?

In class in the morning, we’d talked about two competing but perhaps not contraditory ideas in Brown’s play:

- that Shakespeare’s plays can be performed and embraced from many perspectives besides the one in which they were first written

- that many other kinds of literature besides Shakespeare have claims on our attention, our stages, and our ideas of what literature has been or should be

Those two ideas swirled through Titan Theatre Company’s forceful and compelling production in a tiny theater near the World’s Fair site in Queens. I loved the show, and I kept trying to reconcile those two strains in it: the evident love of Shakespeare, and the equally strong — or perhaps stronger? — desire to write an independent history for African-American theater.

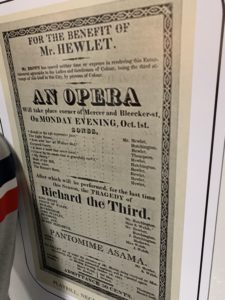

The play re-stages the history of the African Company, founded by Billy Brown in 1820s New York. The story explores a night when their “Black Richard” was attempted to be played opposite Stephen Price’s Park Theater production of Richard III, starring distinguished English actor Junius Brutus Booth. (That famous actor was also, although this detail goes unmentioned in the play, the father of John Wilkes Booth, another Shakespearean actor who was also Abraham Lincoln’s assassin. The three Booth brothers, John Wilkes, Edwin, and Junius Brutus, Jr., famously appeared in a production of Julius Caesar in Central Park in 1864, playing the roles of Mark Antony, Brutus, and Cassius respectively. A year later John Wilkes shot President Lincoln. Shakespeare and white supremacist violence are often much closer to each other than we who earn our paychecks teaching the plays might wish.)

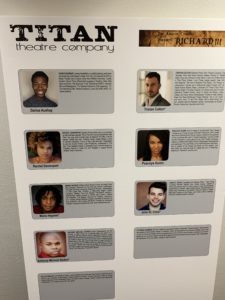

The modern play features a love story between Jimmy Hewlett, who plays Richard, and Ann, who plays Lady Anne. Darius Aushay presents a charismatic and compelling Jimmy-Richard, sliding in and out of the King’s character with a hunch of his shoulder. But Psacoya Guinn’s Ann was the scene stealer: composed, powerful, and with a keen stage presence, she performed her struggle with the part of Lady Ann — “I cannot be such a slack woman as this Lady Ann,” she tells Jimmy — in a way that undergirded the play’s larger struggle with the Shakespearean overplot. Why should she have to submit to the evil, manipulative King? Jimmy explains that everyone play-acts, that “This Ann, she ain’t no different from Lady Ann” — but partly through Guinn’s powerful performance, I could not help but feel that she had the better argument.

Another key character who jumped off the page to the stage was Papa Shakespeare, a formerly enslaved African who’d also live in the islands before he traveled to New York with Billy Brown in somewhat unclear circumstances. Papa Shakespeare, played with Falstaffian gusto by Anthony Michael Stokes, carries a drum and interweaves his own Afro-Caribbean musicality with his roles on stage (he plays Catesby in Richard III) and his sense of what Shakespeare means. He knows that his master in the islands “call me Shakespeare so to mock me,” but he also asserts that “If Shakespeare was a black man, he would be a Griot,” a traveling poet-performing in West African cultures.

Papa Shakespeare loves Shakespeare but also transforms him. Billy Brown’s intentions aren’t always clear. Jimmy insists that Billy wants to co-opt Shakespeare and Jimmy’s performance as Richard III for his “great Negro revolt.” Jimmy’s not sure what he wants. “I get to be loved and to be accepted,” he says to Billy Brown — but he’s also playing an evil king, even if it is one one of Shakespeare’s iconic roles. It’s not always clear what Jimmy’s Black Richard represents: rebellion against artistic limitations? an effort to connect with classical theater from the perspective of a formerly enslaved person? the more personal drama and exchange between Jimmy and Ann? All those things at once?

The African Company’s production of Richard III ends up with the five actors in the Eldridge Street jail, but the modern play finds a new role for Jimmy. “The Drama of King Shotaway” is a now-lost play written by Billy Brown about an Afro-Carib revolution on St. Vincent in the 1790s, possibly witnessed by the historical Billy Brown, staged by the African Company in the 1820s. The play closes with Jimmy finding in these lines an even more regal voice than he’d had when performing Shakespeare:

Restore yourselves, your wives and your children to the inheritance of your ancestors, who inspire your fury and who show you the way. These marvelous, struggling spirits who suffered to you the air you breath; who knit time for you to walk on; who give you stars to cover your body.

Next week in class we’ll go back to Shakespeare, finishing up Timon of Athens before turning to King Richard III. I can’t teach King Shotaway because there’s no extant copy. But I look forward to talking with my students about the ways that the plays we have can imagine themselves into conversation with plays we’ve lost, and those we do not know we’ve lost.

“The African Company Presents Richard III” has a short run and closes Sun Feb 9. Get there if you can!