After watching a great buckets-of-blood play with the news of violent injustice from Ferguson and Staten Island ringing in my ears, I spent a good part of last Friday’s slow and rainy drive home thinking about Simone Weil. I’ve been mulling her quasi-mystical writings on attention for a little while, but the subtext for Theatre for a New Audience’s Tamburlaine was her great essay on the Iliad, in which she describes Homer’s epic as a poem of force:

After watching a great buckets-of-blood play with the news of violent injustice from Ferguson and Staten Island ringing in my ears, I spent a good part of last Friday’s slow and rainy drive home thinking about Simone Weil. I’ve been mulling her quasi-mystical writings on attention for a little while, but the subtext for Theatre for a New Audience’s Tamburlaine was her great essay on the Iliad, in which she describes Homer’s epic as a poem of force:

The true hero, the true subject, the centre of the Iliad is force. Force employed by man, force that enslaves man, force before which man’s flesh shrinks away.

Many of the literature professors flocking to Fort Greene to see this rare production of both parts of Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great will be listening for the hero’s “high astounding terms” and “winning words.” John Douglas Thompson’s exhausting and exhilarating performance hurled Marlowe’s verse high up toward heaven, and Michael Boyd’s fast and violent direction emphasized the harsh charisma of force. On stage, the Scythian shepherd was a hard monster not to love.

He had a good supporting cast, most of whom played multiple roles. Chukwuki Iwuji played Bajazeth in Part 1 and the King of Trebizon in part 2 with wonderful style and flair. My friend Ivan Lupic, who I bumped into during the intermission’s inevitable professors-in-line-for-wine-in-pastic-cups chat session, said of Iwulji’s Bajazeth, “he was good in the cage,” referring to the mighty emperor’s captivity as Tamburlaine’s footstool. The loyal Scythians Usumcasane and Techelles were played with brio by Carlo Alban and Keith Randolph Smith, and their soon-allay — the first of Tamburlaine’s many civilized converts — Theridamas with heartfelt passion by Andrew Holvenson. Patrice Johnson Chevannes’s brilliant turn as Zabina, empress of Turkey, nearly stole the show as she bewailed her own and her husband’s captivity. Morphing into the King of Syria in part 2, Chevannes carried the frustrated regal bearing of her imperial role with her.

The trickiest part in the ensemble to judge was Merritt Janson as Zenocrate, the princess of Egypt Tamburlaine captures, woos as his wife, and keeps by his side even while sacking her father’s city of Damascus. Like Theridamas, Zenocrate demonstrates to the audience that Tamburlaine cannot be resisted; both characters begin by opposing him but are swept forward by his power. Marriage to the hero, and mothering three male heirs in part 2, proves less straightforward for Zenocrate than military allegiance does for Theridamas. In part 2, after Tamburlaine hurls curses at heaven over the death of Zenocrate, Janson shifted to the role of Callapine, Bajazeth’s son who escapes from Tamburlaine’s prison to unite the eastern powers against the usurper. As the mighty warrior struggled toward his final trap, dragging Zenocrate’s monument to Babylon for the last of many battles, Callapine stared down at his adversary with Zenocrate’s face, and her sadness. It was a powerful theatrical effect, overlaying the adversary’s stubborn defiance with the dead wife’s sorrow. The moment recalled Zenocrate’s unsuccessful attempts to get Tamburlaine to spare the virgins of Damascus and the city of her people. As Callapine, she faced him down but still could not persuade him.

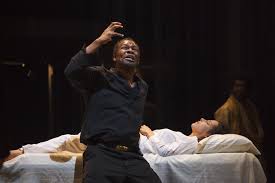

In the end, though, it was a one-hero show. Riding onto the stage atop a cage filled with the crowns of kingdoms he has conquered, drawn by defeated kings, the “pampared jades of Asia” who can “draw but twenty miles a day” (Part 2 4.3), Thompson’s Tamburlaine filled up the stage with ambition, dancing physicality, and rich, incessant pleasure. He wasn’t a frightening tyrant so much as a happy warrior, joyously casting defiance to the stars and to mighty kingdoms. I’ve seen John Douglas Thompson in several roles — as Enobarbus, Mark Antony, and most recently as Satchmo at the Waldorf (I saw it in New Haven before it went to Broadway) — and he’s one of my favorite performers. He grabbed this over-wrought part into one of the enthusiastic bear hugs he deployed liberally among his allies, and also sidled up to it with the passion he displayed most nakedly on Zenocrate’s deathbed. Some of the wine-drinking professors thought he handled the verse about beauty (1.2, 3.3) less powerfully than the verse about conquest, which I think is pretty much true — but I also think that during the face-off of Bajazeth and Zabina v. Tamburlaine and Zenocrate (3.3), no one could out-speak Patrice Chevaness’s Zabina.

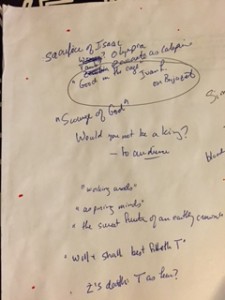

“Will and shall best fitteth Tamburlaine” (3.1), insisted the conqueror, and Thompson’s striding, leaping, laughing, crowing, blood-covered performance drove the play for more than three hours stage time. Would you not like to be a king?, he teased the audience. It cost him everything by the end, but his drive for the visible triumph, the “sweet fruition of an earthly crown” (2.7), rolled over all of us like a breaking wave.

The warriors played on a bloody stage, filled with puddles of stage-blood mopped up with sawdust. Ceremonial buckets splashing on heads marked numerous deaths. The slain virgins of Damascus stood mute and blood-stained behind dripping clear plastic curtains, which we clever professors called Psycho-shower curtains. A repeated motif of the tragic second part of the play involved parents killing their own children: Olympia killed her son to keep him from the torments of Tamburlaine’s army (Part 2 3.3); the hybrid figure of Callapine, played by the same actor as Zenocrate, assailed Tamburlaine and the sons of Zenocrate; and finally, horrifically, after yet another high rhetorical flourish, Tamburlaine stabbed the one of his three sons who eschewed combat. I thought of Derrida’s excruciating reading of the sacrifice of Isaac as yet another body fell on stage: this slaughter of the weak, Derrida insists, has not ended and continues each day. To embody the “scourge and wrath of God” (3.3), as Tamburlaine claims he does: isn’t that to insist on always wielding Abraham’s knife? On seeing all the world’s bodies as sons to be sacrificed?

Tamburlaine’s hubristic climax included burning the Koran in Babylon, which finally turned the stars against him — though perhaps it was just sheer exhaustion at the end of a long night. He passed his crown to his bloody-minded son Amyras and died after a last long blank-verse rage in which he imagines “all the earth, like Etna, breathing fire” (5.3). After three-plus hour of relentless theatrical force, the ending felt oddly abrupt: after so much action, stillness?

Of course the night didn’t end in silence; we applauded the full cast in their blood-stained costumes, stood for John Douglas Thompson, and marveled at his endurance. Driving home in the rain, I thought about force, how it lasts, how much it mars, and how we humans love it.

I heard this weekend that the play’s run has been extended through January 4. Maybe I’ll go back.

Leave a Reply