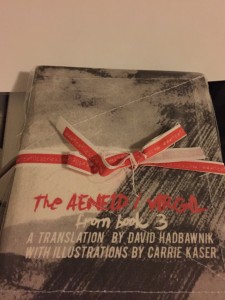

A year ago November I was walking around with the first bits of David Hadbawnik’s translation of Virgil in my pocket and thinking about what it means to be a lover of peotry and ambivalent creature of empire. Two more chapbooks arrived last month — the first wrapped gifts of my holiday season — and though I’m still swirling inside the postlapserian chaos of Inherent Vice — I’ve got about 4 hours to go on the audiobook and am plotting a return trip to the movie — the Aeneid remains the poem that won’t go away. I’m so happy that David’s continuing to work on these translations. Poetic stocking-stuffers for everyone!

This year’s installment is books 3 and 4, Aeneas telling the story of his post-Troy wanderings followed by his abandoning of Dido and her suicide. The two slim volumes with their small pages and short lines have a miniaturizing force, compressing the hero’s wanderings and queen’s erotic tragedy into sharply turned phrases and shocking revelations. Listen to Polydorus, Trojan refugee slain by the treacherous Thracian king after the great city’s fall. He’s been transformed into a bush, and when Aeneas tries to clear ground for his weary soldiers to settle, the bush bleeds and protests:

AENEAS

why must you tear at me?

I’m someone you know, a poor

bastard not worth dirtying

those pious hands over (from III.04)

The human cost of empire is the core subject of the epic, and the millennia after Virgil first dedicated his poem to the emperor Augustus have seen major shifts in attitudes toward imperial unity. Hadbawnik’s lines capture the boredom and sudden terror of empire building, the pain of being a human being forced to uphold more-than-human values. Wandering with his fleet of refugees, Aeneas follows his mother Venus through the mysteries of the Med:

Day by day the adventure

the grind of it

till it’s as exciting as

dragging the trash down to the curb —

my mother the ultimate

performance enhancing drug

language to describe

raging seas

the flash of metal

and gods’ eyes

but what

of the human heart

its dangers

its moments of being

becalmed (from III.22)

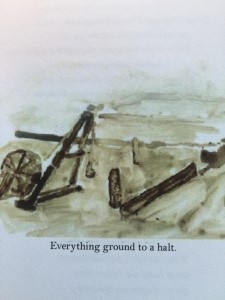

The dramatic climax of this section is Aeneas’s decision, prompted by divine call, to abandon Dido, Queen of Carthage, and sail for his destiny in Italy. Hadbawnik’s book 4 mostly inhabits the doomed Queen’s point of view, sympathizing with her desperate supernaturally-fueled love for the hero who will leave her. It’s hard not to see Aeneas as a monster, even if it’s Dido who, in her parting curse to the departing Trojan fleet, occupies the structural position of Homer’s Polyphemous cursing Odysseus and his escaping men.

The dramatic climax of this section is Aeneas’s decision, prompted by divine call, to abandon Dido, Queen of Carthage, and sail for his destiny in Italy. Hadbawnik’s book 4 mostly inhabits the doomed Queen’s point of view, sympathizing with her desperate supernaturally-fueled love for the hero who will leave her. It’s hard not to see Aeneas as a monster, even if it’s Dido who, in her parting curse to the departing Trojan fleet, occupies the structural position of Homer’s Polyphemous cursing Odysseus and his escaping men.

Traditional and imperial readings insist that the hero must found Rome, and that Dido’s fantasy of an imperial Carthage — “With Trojan arms, there’s no telling what Carthage could do,” fantasizes Dido’s sister Anna (from IV.04) — represent world-historical revisionism, a binding-in of north Africa into what could only be the Roman empire. What I enjoy most about Hadbawnik’s stripped-bare versification of Dido’s tragedy is how the fragments humanize, as if the great Queen, model for so many tragic heroines of European literature, can only speak in bits.

“Where do you run to,” she says to Aeneas, “as I / run to death?” (from IV.16).

Her fate is fire, and its flames peek out from the start of book 4. It starts with love’s “hidden fire / in her veins” (from IV.01), moves from imagined bridal torch to an inner burning that “ate tender marrow / Wound turned silently inside her” (from IV.05) to the gods’ flickering flame in the couple’s hidden rendezvous in a secret cave:

Earth and Juno gave the sign

flame flickered heaven conspired

nymphs

wailed from the highest summit. (from IV.09)

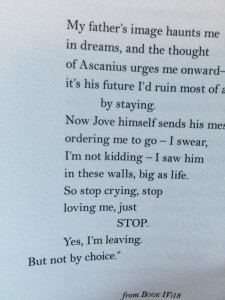

Aeneas makes his lame excuse when Dido catches him — “Yes, I’m leaving / But not by choice” (from IV.18) — but it’s her rage and flames that dominate book 4. Her curse will follow him to Italian shores:

Once cold death yanks my soul

from my limbs my ghost

will be everywhere. (from IV.22)

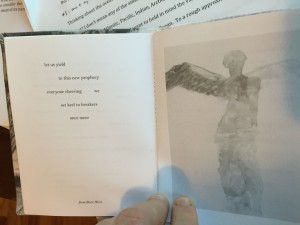

In a faux-theatrical dialogue between “V.” (Virgil?) and “D.” (Dido presumably, not Dante?), she describes her plot to upstage the imperial hero. At the end of this book, at least, our attention isn’t forced toward the future:

Blood, piss, shit

gush out of me staining

my dress. I life my eyes.

Three times I try to lift

my body, three times I fall […]

Iris clips a lock of my hair

with her right hand

and all at once the heat

eases and my life

flies away in the wind (from IV.30-31)

I’m looking forward to seeing what this translation does with the next two books, the funeral games for Anchises and visit to the Underworld.

Leave a Reply