It’s hard to get away from the news these days. During a week that started with “a hot mess, inside a dumpster fire, inside a train wreck” of a debate and ended up with the most powerful man in the world hospitalized, I found myself wanting a break. But it turns out that spending time with the Public Theater’s radio play of Richard II, which is what I’m teaching right now, was less a break than a lens. Shakespeare’s play about a hostile transfer of power makes a powerful, painful response to my regular doomscrolling of news updates. The scene in the middle of the play after Richard returns from Ireland (3.2) felt like a spotlight shined onto today’s news.. One moral of Richard’s reversal of fortune, that power doesn’t last, seems too simple to feel profound. But later in the scene, Richard reveals the human pain of suddenly-visible mortality. That’s the moment that might give us a glimpse into our infected President in this uncertain time.

To be clear, I don’t want to connect the President to Shakespeare’s bad king in order to criticize. We don’t need Shakespeare for that. It is true that many of the things of which Shakespeare’s King Richard appears guilty — manipulation of his peers, abuse of power, dishonesty, an eye for personal gain — will ring familiar to consumers of American political news in fall 2020. The moments I’m thinking of now, however, happen when Shakespeare’s portrait of a king reveals “God’s substitute” (1.2.37) to be a man who encounters his own human limits, perhaps for the first time. That’s the moment that makes me wonder what kind of thinking has been going on inside Walter Reed Hospital this weekend.

We obviously can’t know what to expect from any single case out of the over seven million Covid-19 infections we have seen since in the US since this past spring. We have good reasons to hope and expect that expert medical care and early detection will lead to the President’s recovery. But it’s hard not to think of the risks, and it’s impossible not to think that he, himself, might be feeling the cold breath of mortality. He may not want to tell us what he’s experiencing — but maybe Shakespeare already has?

National leaders don’t extemporize in iambic pentameter these days, but I wonder how many of Richard’s thoughts might be running through his mind.

When Richard arrives back on English soil and hears that a rival has taken the field against him, he first claims to trusts the mystical power of his own authority:

Not all the water in the rough rude sea

Can wash the balm off from an anointed king.

3.2.54-55

So far, so confident. Richard, like other leaders we might hink of, likes to interrupt when others try to speak, as we’ve seen in the first two acts. He’s in control, so far. Or at least he thinks he is.

But the king’s forces melt away. His Welsh allies head home (2.4). His powerful uncle York, whose ambivalence when caught between his king and his nephew Bolingbroke carries the whiff of political cowardice, shifts to the side of the rising Bolingbroke. “I do remain as neuter” (2.3.159), pleads York at first, before effectively casting his lot with Bolingbroke. These betrayals push Richard to self-dramatized misery:

Of comfort no man speak!

3.2.144

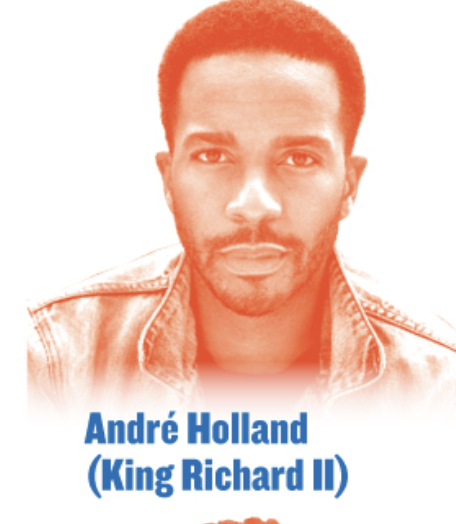

At this moment Richard voices an anxiety and self-doubt that no political leader wishes to reveal. I can’t help hearing these lines, as performed by the charismatic Andre Holland, as a kind of secret human history of our virus-stricken President, the words he won’t — can’t — utter, perhaps not even to himself:

Throw away respect,

Tradition, form and ceremonius duty,

For you have but mistook me all this while.

I live with bread like you, feel want,

Taste grief, need friends. Subjected thus.

How can you say to me I am a king?

3.2.172077

“Subjected thus” — what does it mean when a ruler who feels himself invincible suddenly becomes vulnerable? The depth of feeling seeps out from Andre Holland’s gorgeous American voice. These lines speak what we have not been allowed to hear this past weekend. We know it must be true: he must live with bread, feel want, taste grief, needs friends. But will he show it?

My students and I have been listening all week to this spring’s brilliant and searing production of Richard II, dedicated to Black Lives Matter and featuring a mostly non-white cast. Director Saheem Ali frames his production as an interrogation of Shakespeare and the place of theater in American culture during the hinge of 2020. The podcast episodes feature interviews with the actors and with Shakespeare experts including the amazing Ayanna Thompson, among others. Might the play make a better way to think about current events than refreshing Twitter?

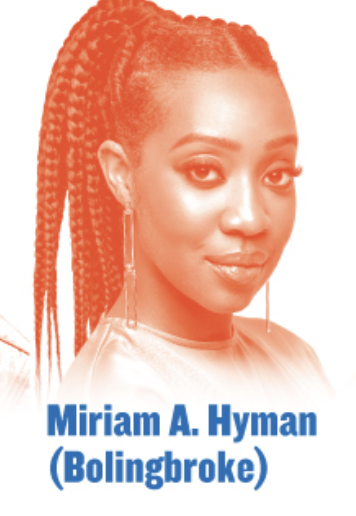

So far, my students haven’t missed much about how topical this play feels. We spent some time last week interpreting the thoughts of Miriam Hyman, the Philadelphia-based actor and rapper who plays Bolingbroke, about the moment in which the rebel-who-will-become-king dedicates himself to “Mine innocence and St George” (1.1.84). She describes hearing this line during rehearsal and then imagining Bolingbroke the “exile” as a spokesperson for George Floyd and the BLM protestors. In her searing, powerful performance, she makes this four century-old play speak to 2020 urgencies. Miriam Hyman’s Bolingbroke is here for the same storm that my class started the semester with, in Claudia Rankine’s poem “Weather,” written while the protests were happening this spring. “We are here for the storm / that’s storming,” Rankine writes. Richard’s personal corruption, his glee at the passing of John of Gaunt (a Duke, not a Supreme Court Justice, but it seems close enough…), his manipulation of his subjects: it all seems a bit too on the nose.

So, how to you resist the king? “Vote him out,” one student said, an anachronistic if understandable response. “Peaceful protests?” wondered another. Miriam Hyman performs Bolingbroke’s version of the #resistance as a powerfully direct, in the streets response that reminds me, somewhat, of a more conclusive version of the Women’s March of January 2018.

Just who exactly is writing the script for 2020?