Thinking about this play today, I hear the first word in the gravel-mouthed syllables of Martin Prochazka, a great Czech Shakespearean who I first met at a bar in Prague about four years ago:

Thinking about this play today, I hear the first word in the gravel-mouthed syllables of Martin Prochazka, a great Czech Shakespearean who I first met at a bar in Prague about four years ago:

“De-terratorial-i-zation!”

That’s what it’s all about. Or at least that’s what I thought about after seeing this show at St. Ann’s on March 27 with an eager dozen or so of my students.

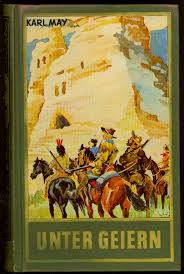

Without digging too deeply in Deluezian & Guattarian weeds, the deterratorializing impulse in The Wooster’s Group’s latest (and third) iteration of Troilus and Cressida, now entitled “Cry, Trojans,” organizes this still-bizarre but unexpectedly streamlined version of their Red Indian take on the Trojan half of Shakespeare’s Trojan war play. Casting Trojans as Native Americans, whose costumes and stage dancing inhabited visual cliches made manifest in the “spirit guide” video monitors arranged on the four corners of the stage, relocated classical heroism into a landscape at once prehistoric and celluloid. Ben Brantley didn’t like it, but he didn’t try very hard to figure it out.

I’ve been thinking and writing about this production for several years. I saw it first in Stratford in 2012, at the International Shakespeare Conference, and then a second time in the bitter cold in January 2013, downtown at the Performing Garage. That was a workshop production, in preparation for the current run at St Ann’s in Brooklyn.

You’d think after three evenings with these Woosters I’d have a pretty good sense of what’s happening. But the strangeness lingers.

Deterratorialization works to unsettle, even unmoor familiar associations. What are we left with when we watch a story of the Trojan War with no Greeks and Trojans who spend their time starting a video screens we the audience can’t see very well?

My experience of this Wooster production makes me hyper-aware of how theater requires us to parse out attention, looking now as Scott Shepard’s stoic Troilus, now at Kate Valk’s erotic and playful Cressida, sometimes at the video monitors showing Splendor in the Grass or The Fast Runner. Where’s the right place to put your attention? Watching this play means deterratorializing your eyes.

The second word is mediation. This term has become my Wooster-watchword, first pronounced in 2012 to a pint-quaffing gathering of mostly hostile Shakespeare professors at The Dirty Duck, the Stratford pub where we gathered after seeing the 2012 production of this play, in which the Woosters’ Trojans stage-fought against the heroic stalwarts of the Royal Shakespeare Company. “It’s extreme mediation,” I said to the skeptics. “That’s what the screens do. It’s how we live today. What do we all look at when we stare at our tiny beloved screens?”

After the workshop in the Garage last winter, I managed to get Liz Lecompte, the play’s director and co-founder of the Wooster Group, on the phone. I spun her my theory that their production sliced most of the epic warfare off this love-and/as-war play, so that the alienating moves almost but not quite prevented our access to the core melodrama. I said I thought Pandarus’s song was the key thing: “Love, love, Nothing but love…”

(It turns out the the love-and-violence subplot of the play extended to the original cast back in 2012, according to the Times.)

They cut most of that song in the new version, and in a few ways that streamlining unsettled the emotional reading I gave the play in 2013. The 2015 version was a clearer, more foreceful Cry, Trojans than what we saw in the Garage — the playbill is, especially for the Woosters, a model of clarity — but perhaps also a darker one.

My students were shocked that the love scene pantomimed rape, with Troilus scooping Cressida over his shoulder and running in circles while she flailed with her fists and wailed — not with full emotional force, perhaps, but in a kind of symbolic dance. After he put her back on her feet, she pronounced the invitation that scandalized the play’s Victorian editors:

Will you walk in, my lord?

In Valk’s pouty delivery, this line does to Troilus what he’s just done to her by carrying her across his shoulder: embarrasses with raw eroticism. Her sexuality unnerves him, assails him, and the two, like the gorgeous doomed lovers played by Warren Beaty and Natalie wood on the monitors, have their once-separate selves over-written by the roaring waterfall of eros. There seems no more choice in their passion than in Cressida’s later ambivalent yielding to Diomedes in the Greek camp. Love is not choice but submission to a story that writes the self, not a story we can write ourselves.

(Speaking a story we can’t write ourselves, the Woosters invited me to do a short dialogue about the play earlier this spring — but when my train ran late, they went on without me. Oh well. I have answers for those questions, if the occasion ever re-arises…)

This darker and more entangled extrapolation of the love plot makes the central figure of the play not so much either of the lovers but the go-between, Pandarus. As played by Greg Mehrten, who also plays King Priam and, briefly, the satiric Greek Thersites, the “sleazy uncle” (as my students called him) occupied the uncomfortable heart of the drama. In an atypical move for Shakespeare, this figure of moderate rank gets the last word at play’s end, and bequeaths that audience his “diseases.”

When I teach that moment I like to talk about Troilus as satire, exposing the elite martial codes and the plays that celebrate them, including among others Shakespeare’s Henry V. But this time through I also felt Pandarus spoke for the lost lovers and the meet cute during wartime plot he’d almost smuggled past the epic censors. What if his sleazy love-plot is the disease, and we’ve all caught it? They may have mostly cut his song but I still heard it when I was driving home on midnight highways —

“Love, love, nothing but love…”

Running through April 19th in DUMBO!