A few stats for 2016 —

~ 12,400 page views. That’s about what it’s been for the past several years. Roughly 7000

32 posts. Up slightly from 30 in 2015, but still down from 2014’s 55 (!).

Most in one month was June (6, all theater reviews from #artsideas in New Haven). Least was zero in May.

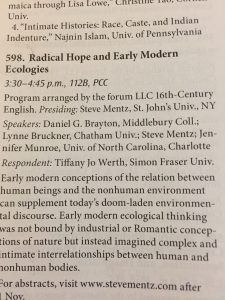

Sixteen — exactly half — of the blog posts were theater reviews. I’ll collect them in a separate post. Of those sixteen, nine were plays from the Renaissance (or close to it.) Four were responses to academic events.

Maybe I’ll start doing something different with the Bookfish in 2016?