Here are the brief remarks I made to the Zoom-sea at an event celebrating the works and legacy of John Gillis.

[And here’s the full 90 min Zoom, featuring many fabulous people!]

I presented four quick snapshots about what John’s work means to me –

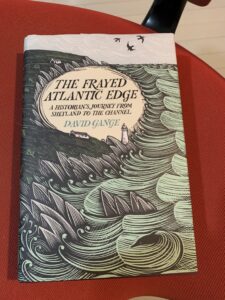

- I first met John through Islands of the Mind, which I must have read around 2006 or so, as I was making an oceanic turn in my own literary scholarship. John’s introduction of islands as a “third place” between settled land and chaotic sea, and his presentation of “islomania” as recurring cultural dream have stayed with me. But my favorite thing in this great book is the historian’s gesture toward the poetic imagination. The book’s subtitle, “How the Human Imagination Created the Atlantic World,” set up descriptions of the entanglements among real islands, from Iceland to Bermuda to Tahiti, and fictional ones, from St. Brendan’s isle to the island of California to Utopia. Beyond its erudition and range, what I cherish most about this book is its generosity. Like the sailors it chronicles, the book invents as it explores – half create[s] and perceives, to adapt Wordsworth’s formulation. I love its open-ness.

- My second snapshot takes me and my then 10 year old son Ian to visit John and Tina at Great Gott Island, Maine, in 2011. I’d met John through the Fluid Frontiers conference, and he kindly invited us out to their private paradise. “Islands are not utopias,” he cautioned us as we tromped through mossy paths around the island. (Here’s a picture of Ian and John, heading into the woods.) It was a charmed day, with a special fisherman’s magic: I caught a juvenile mackerel on my first cast from the “apron” of granite that surrounds the island, and Ian caught another on his last cast of the day, as we were about the leave the dock that Tina calls the heart of the island, the place through which people come and go. I can still feel the thrill of accessing secret knowledge and oceanic experience in that summer’s day off the coast.

- Back to scholarship – I’ve probably never been so touched at having been cited by another scholar than when I read John’s web-essay “The Blue Humanities,” which appeared in the NEH journal Humanities in 2013. At that point I wasn’t myself sure what the blue humanities was, though I’d been using the phrase for a few years. John showed me. His essay reflected back to me what happens when you let the waters in, to stain and suffuse scholarship. As it happens, during this hell-year of 2020 I’ve just last month signed a contract with Routledge to write a book called, “An Introduction to the Blue Humanities.” It’s a labor of love for me that has crystallized through John’s hearing and reimagining that phrase back in 2013.

- My last snapshot features me in a sleeping bag, surrounded by my family, on the living room floor of our house on the CT shoreline. We’re huddled together in the dark waiting for Hurricane Sandy to descend upon the coast. I’ve got a headlamp on, and I’m eagerly reading The Human Shore. I like to read Gillis books during hurricanes. I had read Tina’s great book Writing on Stone during the blackout after Hurricane Irene one year earlier. What do the Gillises have to do with global storm systems that rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere? It’s not that their work and legacy resembles a hurricane’s violent disruption. Although…if we think Superstorm Gillis as an organizing principle, a system whose structures have global reach, oceanic origins, and planet-sized scale…well, I don’t know. It might not be the worst symbol of this great scholar’s work and influence!

Plus some bonus bibliography:

John Gillis, Islands of the Mind: How the Human Imagination Created the Atlantic World (Routledge 2004)

Christina Gillis, Writing on Stone: Scenes from a Maine Island Life (2008)

- I read this one during a blackout after Hurricane Irene (August 2011)

John Gillis, The Human Shore: Seacoasts in History (2012)

- I read this one during the blackout after Hurricane Sandy (Oct 2012)

“The Blue Humanities” Humanities 34:3 2013

John Gillis and Franziska Torma, eds., Fluid Frontiers: New Currents in Marine Environmental History (2015)