What does she read, behind closed stones eyes gazing forever at a blank page?

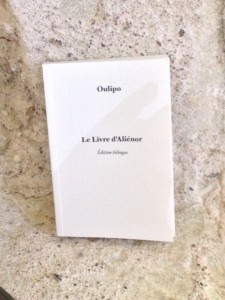

That’s the question that the tomb effigy of Eleanor (Fr Alienor) of Acquitaine poses in Fontevraud l’Abbaye, and during the summer of 2014, the Oulipo is on the case. Their installation combines multiple media forms: a bilingual printed book of poetry, which they give away in the Abbey church, two large-format copies of the same book, for browing near the four tomb effigies, projected images of the poems superimposed over a view of the four effigies from above, and a website.

It’s an amazing assemblage of works historical and poetic. The scholars and poets who put it together examine four main contenders as representing Alienor’s stone book: the troubadour poetry that was more or less invented by her grandfather, William IX; a religious text such as a Psalter or Bible, which seems the most likely thing for a tomb reading; her own historical experience as wife of two kings and mother of two more; and the context of the three effigies around her, including her husband Henry II Plantagenet, her son Richard Coeur de Lion, and her daughter in law Isabella of Angouleme, who was married to her son John Lackland.

The Oulipo explain their project as an attempt to bring contemporary poetry into medieval history and also as a response to today’s “transitional period” of media technologies, in which the printed book “coexists with new digital media” (126).

In typical Oulipo fashion, the poets create constraints for their works, first imitating William IX’s famous poem about “just nothing” (134), and later creating a series of variations on the sestina, a poetic form invented by the Provencal troubadour poet Arnault Daniel in the 12th century.

There are some gorgeous responses to Alienor’s book, which the exhibition highlights with flood lighting, as “both void and full” (211; “”Le rein, le plein” 96 — I’ll quote mostly from the English versions here, but sometimes the translation from the French abandons sense for form). There is one poem in English is both versions; it celebrates “A page that will not turn” (100, 214). Other poems playfully retell the history of this famous queen and cultural icon:

Bending over the ear of Eleanor of Acquitaine, William IX, the troubadour, said, “Grow. We’ll sing for you, little one (188).

A key thought experiment for the Oulipo explores the idea of Alienor “in the Avant-Garde” (171-87) of both the 11th and the 21c. Marcel Benabou suggests that her book represents a crucial, usually invisible production in the cultural history of ideas of nothingness, the “poem of zero words” (186). This “precious conceptual tool” (186) illuminates medieval debates on the value and meaning of void, in which William IX’s lyric is so important but theological disputes have their places also. For the Oulipo, the blank book also speaks to contemporary poetics of emptiness via Blanchot, Francois Le Lionnais, and other 20c theorists. Alienor’s book thus becomes “an anthology of poems of zero words” (186), a visible, even tangible representation of what Wallace Stevens calls “nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.”

It’s an ingenious reading, and just the sort of combination of historical context and contemporary poetics that I love. But it’s not the heart of the matter, at least not for me.

It’s an ingenious reading, and just the sort of combination of historical context and contemporary poetics that I love. But it’s not the heart of the matter, at least not for me.

I came to Fontevraud with my family, including my wife Alinor and her mother Molly Sterling. Molly has been there a few times before, and has been thinking about Alienor and the Abbey for a long time, to the point of adapting the spelling of her daughter’s name from the French Alienor. So, lucky me, I got to visit the place where my love’s name was born. I found it full of poetry.

William’s poems about nothing, after all, are also love poems, after a fashion:

Nothing will be well accomplished

In love, without paying homage,

And being, to those far and near,

Compassionate,

While giving to those at your court

Your fealty (145).

Walking the grounds of the Abbey, listening to a recorded performance of a hymn to earthly perfection in Racine’s Esther, reading about Jean Genet’s description of the lives of prisoners in the 1950s (though it’s not certain he was in Fontevraud itself) — it all assembles a small human place of perfection, as Balderic describes the foundation of the Abbey by Saint Robert of Arbrissel in the 11th century (154-59).

A brilliant and intricate more-than-sestina by Michele Audin (written in a form called a “Josephina,” in which the length of each stanza increases from one to twelve lines), laments to opacity of historical distance, in which all elements of everyday life were different and beyond recapture. One thing remains:

…all of the gestures were different

except those of love, of course, and those that lead up to it (198).

Leave a Reply