The last time Paul Thomas Anderson had a Pynchon movie come out, I hustled myself across town for a matinee on opening day. This time, with a new one “inspired” by Vineland (1990), I watched it in the CT ‘burbs with my son, in one of those Cinemark theaters where the seat vibrates and lurches in time with the film. I’m not sure about those seats, but it wasn’t a bad way to watch the gorgeously filmed car chase in the wilds of northern CA that was the movie’s high-paced ending. That ending was for me the fork away from Pynchonland, at least a little bit – but the whole show was a great ride!

Once again, after the latest film, I’m left thinking about sentiment. Is PTA too sentimental, even for “late” (ie, post-Gravity’s Rainbow) Pynchon? Thinking about the hidden author’s second act after Mason & Dixon (1997 – but according to pynchonistas, at least partly written in the immediately post-GR mid-1970s), he appears to be making peace with the sentimentality that the early novels mostly lampoon. Doc’s sometimes dislocated pining for Shasta Fay in Inherent Vice became, in PTA’s film, a resonant core that partly inverted Pynchon’s characteristic scattering. In Bleeding Edge (2013) and in PTA’s latest film, that heart is parenthood – the film’s lingering focus Chase Infiniti as the teenage Willa Ferguson (Prarie in Vineland) recalls Maxine’s final glimpse of her young boys in Bleeding Edge. Pynchon’s been an Upper West Side family man since the 1990s – at one point I read that he volunteered as a crossing guard for his son’s grade school, and the image of old man Tommy P. calming uptown traffic is too good not to be true – and the choice to film the later, softer, more human novels feels right. (Could anyone ever film Gravity’s Rainbow? Probably not – but I’d love to see someone try a 50-episode “mini”-series or maybe just an animated short about Bryon the bulb?)

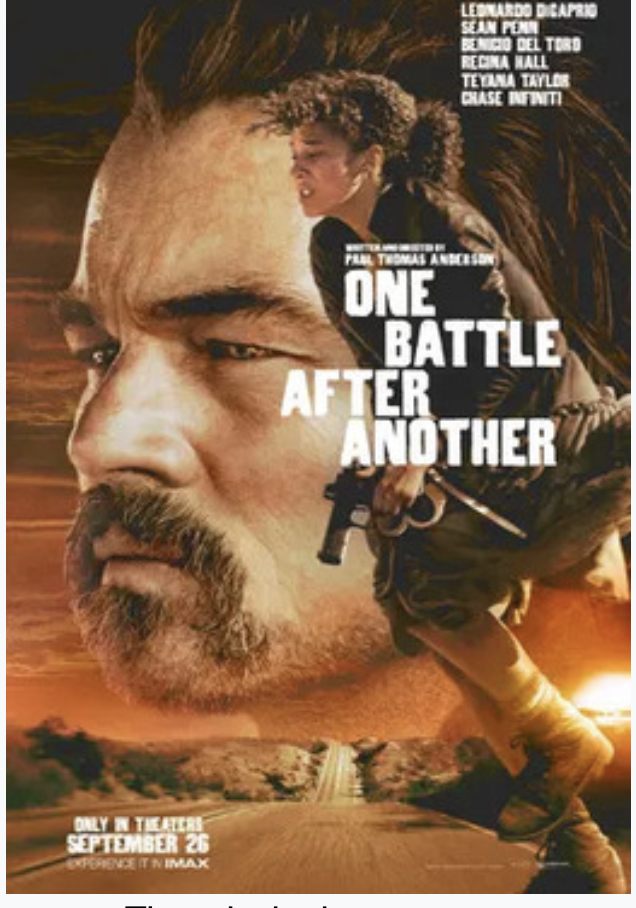

Watching “One Battle After Another” was so much fun that I feel bad nit-picking the parts that felt, to this Pynchonista, a bit off. The pacing, the score, the costumes, the scenery, the camera-work were all endlessly entertaining. I have a special affection for the rural northern CA utopi-ish landscape in which much of Vineland is set, because my late father-in-law used to live in Philo, between Boonville and Eureka, which one-time hippie towns are at least plausibly real analogues of Pynchon’s always at an angle to reality locations. (The film is partly shot in Eureka and among the gorgeous redwoods where we scattered family ashes a few years ago.)

As with PTA’s film of “Inherent Vice,” the acting was brilliant, with big stars – in this case Leonardo DiCaprio, in the earlier one Joaquin Phoenix – taking on Pynchonesque tics. Leo plays Bob Ferguson (nee Zoyd Wheeler), Teyana Taylor gives a rousing turn as Perfidia Beverly Hills (Frenesi Gates), Sean Penn is the corrupt yet complex Steven J. Lockjaw, and Benecio del Toro the serene sansei Sergio St. Carlos. Theirs were the biggest and most engaging faces on screen, but Regina Hall’s Deandra (a semi-analogue of DJ, maybe?) wasn’t far behind, and the full cast was excellent. I kept being struck by PTA’s creative and frequent use of the close up – the camera loves all these faces, and many images linger: Deandra weeping when being interrogated, a pregnant Perfidia firing an assault rifle, nervous Bob playing with explosives, and Lockjaw trying to assume a perfectly blank expression while being (possibly) initiated into an elite white supremacist cadre were among the most memorable. Maybe best of all was Sergio St. Carlos beatifically preparing himself to be hassled by the cops after admitting to having had “a few small beers” before being pulled over – though of course we know that he’s at that moment distracting the forces of the law so that Bob can escape to rescue his daughter. (I might also put in a quick word for the stoned Bob’s interview with his daughter’s history teacher, letting her know that Ben Franklin was a slaveowner before becoming an abolitionist. Watching this funny scene, I couldn’t help thinking it was a call-back to the 22-year old Sean Penn’s early role as surf-stoner Jeff Spicoli in 1982’s “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.”)

Chase Infiniti’s Willa, the lost child who Bob brings up as a single Dad after Perfidia skips, becomes increasingly the film’s emotional heart, in ways that were perhaps a bit too sentimental even for late Pynchon. She’s an impressive young actor, and she gave the big star playing her Dad a nice teenager’s glare and backchat. In some ways, as with Shasta in “Inherent Vice,” Willa is required in the film to carry maybe too much redemptive energy, to be the magic child who can save the world or at least the family. My personal reading of Pynchon remains firmly postlapsarian and convinced that the world can’t be saved, which of course doesn’t mean that we should not keep trying. The film, like the novel, both sympathizes with the revolution and also critiques it.

Was Willa, or maybe even the whole film, too sweet-sad to be fully Pynchon-ish? So many of the ingredients of the stew bubble nicely together – the paranoia, the doper jokes, zany names, characters who are mostly allegories but also sometimes, as if by accident, real people. PTA follows Pynchon’s lead in presenting dizzying turns of the betrayal wheel, so that the radical revolutionaries and their white supremacist adversaries fight each other, resemble each other, and become oddly, not to say erotically, entangled. Every We-system is also a They-system, as the man says.

There’s a sweetness in the film’s politics and its devotional expression of familial love that comes to the fore in the second half, after Perfidia leaves, first for witness protection and later for parts unknown. Bob’s commitment to radical politics matches up with the spirit of Pynchon’s novel, even if the joys of the People’s Republic of Rock n Roll don’t appear on screen.

I’m tempted to say that the biggest gap between novel and film is that Pynchon works through systems and PTA through individuals. In this sense, the camera’s close ups might be symptomatic – the film director loves faces, while the mad genius novelist constantly invents new and interlocking groups.

Some of the non-Pynchon elements in the film, especially the supremacist Christmas Adventurers who pledge themselves and their controlling violence to St. Nick, and also the name Perfidia Beverly Hills, felt at least as Pynchon-y as old Tom’s versions.

The almost-last close ups in the movie were on the rolling asphalt roads of Humbolt County, and in my vibrating seat I felt as if I was driving over the mountains back in time to see my father in law again. Bob arrives just a bit late, but it turns out – unsurprisingly – that Willa has already saved herself. Will there be a full family reunion? Maybe, or maybe not – but the bad guys have been avoided, at least for a while.

The central baddie in the film is Sean Penn’s Lockjaw, an ambitious military man whose erotic obsession with Perfidia becomes visually too-obvious to an early moment in the action. Penn’s combination of coiled intensity and physical awkwardness made him become a compelling villain, in a way reminiscent of Bigfoot in Inherent Vice. He’s cruel and exploitative, especially in his dealings with Perfidia and later her daughter. But he, too, gets caught and chewed by the machine to which he dedicates his career. As in Pynchon’s novel, it’s ultimately his own system that prevents him from wreaking his revenge on the lost child. And as in the novel, there’s something unsatisfying about that ending, even though Willa has already, in a Hollywood touch, gunned down one of the other Christmas Adventurers.

How must we act in the fact of injustice? What happens when righteous revolution curdles into betrayal, or gets displaced by other human needs and systemic forces? PTA’s latest film, even though it’s less directly an adaptation than “Inherent Vice,” and of course misses many great Pynchon-bits, from the thanatoids to the toobfreex, not to mention great characters such as Weed Atman and DJ the ninjette, maybe gets the balance pretty close to right, the sweet along with the bitter, the playful insinuating itself into the tragic, so that, in the end, like Byron the immortal bulb and impotent revolutionary, we find ourselves enjoying it.

I’m hoping to see it again soon!