There’s no easy way to do justice to 20-odd papers and responses, five linked sessions, and over eight Zoom-hours rolling through my ice storm Friday in the northeastern USA. I had hoped, when I responded to Kim Peters and Phil Steinberg’s intriguing CFP some months ago, to end the evening with a round of craft cocktails at a suitable downtown locavore eatery. But Zoomtopia won again, which means we juggled time zones from Australia to India, Japan, Taiwan, Hawai’i, the UK, Germany, and elsewhere.

I’ve never been to a geography conference before, though I’ve been greatly influenced by reading oceanic geographical work by Peters & Steinberg, among many others, for years. The range and allusive complexity of today’s papers was, frankly, a bit overwhelming. It’s great to swim in new waters, but (to mix my watery cliches) I came away feeling as if I’d been drinking from a fire hose.

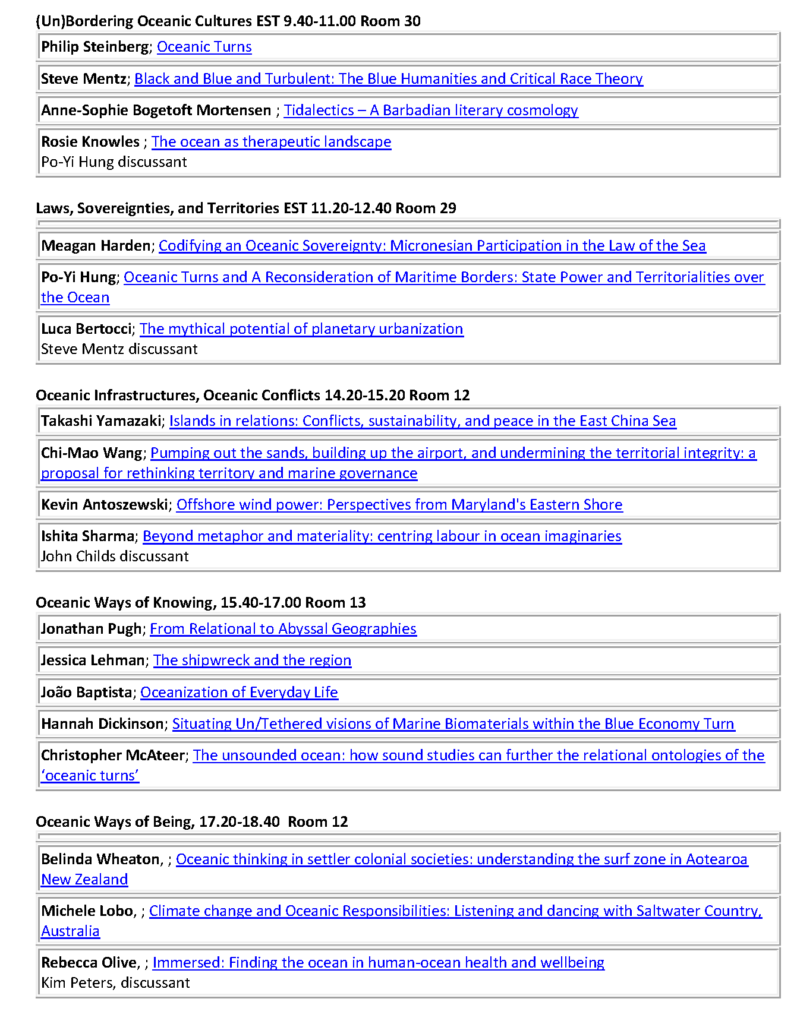

There were five separate sessions, each tracing Oceanic Turns in different modes – cultures, sovereignties, infrastructures, ways of knowing, and ways of being. Phil Steinberg’s collective intro to the first session also catalogued six distinct modes of oceanic turning – spatial, material, decolonizing, posthuman, globalized, and (blue) economic. Looking at the list, I count 18 individual talks + four discussant responses. Blog-readers will forgive me if I don’t enumerate every one!

Instead, I’d like to meditate on this lively event by jotting down a series of active tensions and analytic terms that the papers as a group have me buzzing about. To some extent it may be that the tensions reveal problems to be addressed, while the terms offer themselves as possible solutions. But I suspect it’s not so simple; the binary tension-or-term frame might be my quick-twitch way to oversimplify complex ideas and the many “turns” we experienced across these sessions. I did keep thinking, as we rolled on through the day, especially when I snuck outside between sessions to scrape 2 inches of ice off my driveway and car, about two larger oceanic structures. So I’ll wrap up my bloggy post-game by naming these inhuman structures, which continue to stretch and shape my thinking about tensions, resolutions, oceans, other watery bodies, and how we might think and represent them.

But first, without commentary, here are my notes on tensions and terms —

Tensions

- two modes of thinking: poetic/theoretical v. political/legal

- “detachment” v. engagement

- infrastructure v. myth

- abyssal v. island

- marine science and religious faith (this one is less an opposition than…something else – historical transformation? analogy?)

- local v. native v. Indigenous

- turns v currents

Terms

- “porosity” (or transcorporeality)

- relationality (used in many presentations, and picked up powerfully by the concluding session, with speakers mostly coming from the South Pacific or Southern Ocean)

- “experience” (or “the skin”) (or “encounters”)

- “trans-border”

- “interconnectedness” (or also “interlacing”)

- “Anthropony” (a lovely term!)

- “turbulence”

Plus – some quick thoughts about a pair of post-game structures —

Inhuman Structures

- tides

This rhythmic structure came up early with Anne-Sophie Bogetoft-Mortensen’s great paper in the first session on Brathwaite’s “tidalectics.” It’s always true that oceanic thinking flows in the patterns of flood and ebb. At times in my literary corner of things I worry about an excessive metaphorization of tidal systems, but one of the great things about a wide-ranging set of papers is a varied menu across the metaphor-material divide. We engaged with real tides eroding real sands, with poetic formulations, and a variety of things in between. Tide and time and tempest, all of my favorite things in one neat etymological package.

- ocean currents

The other oceanic structure that I kept thinking of across these papers, especially the many about geopolitical conflict and territorial claims over oceanic spaces, is the complex global pattern of ocean currents and prevailing winds. In the historical period of my own scholarly training, the 16th-17th century in Western Europe, these patterns were both largely unknown and significantly controlling: the main reason so many European sailors arrived in the Caribbean in the 16c was that they learned to follow the North Equatorial Drift. It’s not that the currents and gyres are static systems (are there any static systems?), but that their rates of change are mostly beyond human scale, though it’s possible the climate change will alter that rate in coming decades. I sometimes think about the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Gyre as the most consequential actors in transatlantic modernity – but I have not really developed a language or interpretive scheme to make sense of the currents as actors. Maybe that’s next year’s project?

With thanks to Kimberly Peters and Phil Steinberg, who organized this raging flood of a day-long set of sessions, and to all the presenters and members of the audience!