The way in to the old story requires that you inhabit it uncomfortably, all elbows and knees, pushing up on its sides and spilling over the edges. Few stories are more familiar, more urgent in our era of rising seas, or – in the end – more confining. Wearing it from the inside includes shaping this ancient garment to fit, or to not-fit, but differently. Ark-making and boundary-policing – who’s on, who’s off, who gets what resources on the voyage – can be a brutal business. The genius of this book’s re-population of our archive of ark-stories comes through its range and deftness, its ear for aphorism and eye for detail. Once you’ve read Noah’s Arkive you’ll never look at that Playmobil Ark the same way again.

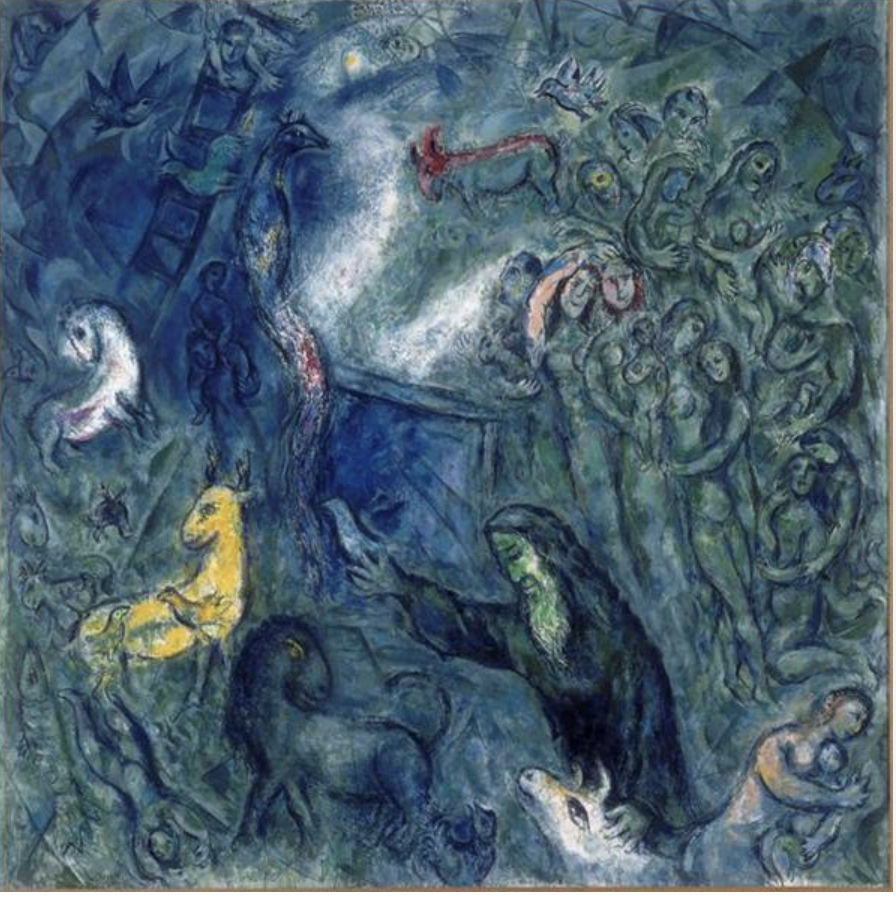

“Perhaps the worst thing you can do,” Cohen and Yates remind us repeatedly, for the last time near the text’s end, “is to think you are not on an ark.” The exclusionary choices, patriarchal structures, and resonant figures such as Noah’s wife, the dove, and the raven, contain us, even if we’d like to think that in the Post-Flood we have escaped them. Ark-stories, including the core narrative in Genesis, novelistic retellings from Tim Findlay to Jeanette Winterson and many others, a gorgeous tumult of images from medieval manuscripts and paintings to modern stories and sci fi novels, encircle our ideas about crafting a refuge in a hostile environment. Maybe we’d like to get off the boat – but where can we set our feet in a flooded world?

Many of us in the world of premodern ecotheory have been listening to stories of the ark from these two writers for years, so that visits to the Ark Encounter in Kentucky and the Ark of Safety in Maryland, presented early in the book, have a nostalgic, pre-pandemic feel. Cohen and Yates are among our most engaging spinners of eco-theoretical narratives, and I suspect I won’t be the only reader who will wonder which of these two distinctive voices is peaking through at which section. I think they’ve successfully achieved a real blend of voices in this collaboration, though I hear more of Yates’s voice in the discussion of Garret Serviss’s The Second Deluge (1911) and its King Lear subtext, and a final distinctly Cohen-flavored excursus into Chaucer punctuates the final pages – though perhaps they will tell me these are the wrong identifications.

The book’s chapter titles comprise an out-of-order poetics that asks us to jumble up and make messy our ark-thinking. We are first instructed in “How to think like an Ark,” then cautioned not to lose ourselves in fantasy because there are “No more rainbows.” We splash around “Outside the Ark,” measure cramped spaces “Inside the Ark,” and consider “Stow Aways” from the Devil to unicorns and woodworms. Perhaps my favorite chapter considers “Ravens and Doves” as, among many other things, models of reading and modes of ending – it’s hard not to value the freedom of the raven who never returns to Noah’s hand, though the allegorical imperatives of the dove seem so deeply ingrained that I wonder how possible it is to choose just one bird. Should we “Abandon Ark?” Or is “Landfalling” the only possible goal, as the last chapter suggests?

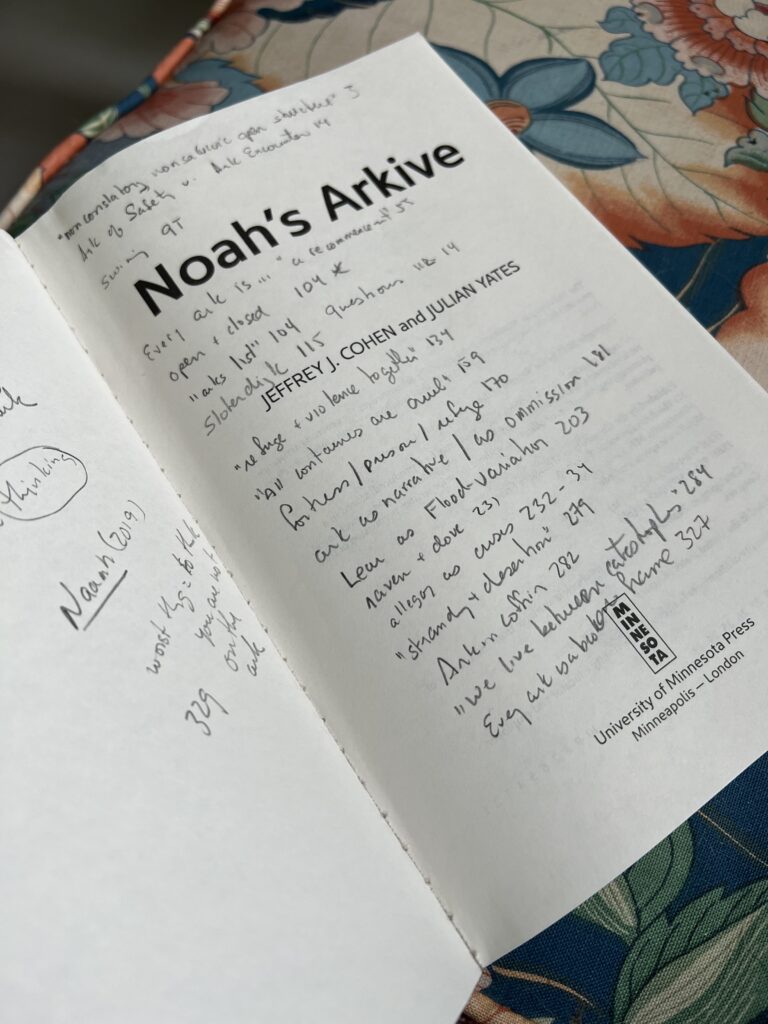

My messy notes contain an incomplete list of aphorisms that suggest a line of t-shirts and coffee mugs in these busy critics’ futures. “Every ark is a recommencement.” “The arks yokes refuge and violence together.” “All containers are cruel” (with a lovely excursus here into Peter Sloterdijk’s speherology). “We live between catastrophes.” “Every ark is a broken frame.” “Every ark sails the crosscurrents of its days.” An ark is a “technology for stranding and desertion.” “Stories of landfall are all clockwork tales.” These fragments are incomplete, out of order, and unpaginated – my apologies – but narrative order, and citation practices, too, are arks of confinement against which some partial freedoms can be asserted. Plus this is an informal bloggy sort of thing, written just after I finished the book!

I closed the end of of Noah’s Arkive last night, knowing that this is a book that many of us will return to, in and beyond the classroom, with two somewhat conflicting thoughts. The first is about how this book calls together a dispersed community of scholars, writers, artists, and fellow travelers whose ideas, stories, and insights populate these pages. The main text returns to a few dozen primary reworkings of the Noah story, especially Timothy Findlay’s Not Wanted on the Voyage (1984), Kim Stanley Robinson’s Aurora (2015), Jeanette Winterson’s Boating for Beginners (1985), Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones (2011), Sarah Blake’s Naamh (2019), and many others – but for academic readers like me the volume’s generous end notes represent, like the kitchen in a house party, a place where all sorts of fun people gather. Though I know that it’s hard to print long books these days, and Noah’s Arkive weighs in at a chunky 406 pp, I would have welcomed a bibliography of primary sources, full lists of images, and maybe even a “Suggestions for further Ark-Reading” section.

The second lingering thought, which is less fully-formed than is the sheer pleasure of having being in the company of so many excellent, smart, and perceptive people as I rationed myself to one chapter per day over the past week, is to wonder what kinds of new futures that old patriarch Noah might have. The seas, we know, are rising, again. Another book I’ve enjoyed recently, Birnam Wood by the New Zealand novelist Eleanor Catton, contains an extended post-apocalyptic bunker subplot that has a very Ark-like flavor. Her fictional American billionaire has ulterior motives for his New Zealand hideaway – but plenty of similarly gated communities are mushrooming up all around the globe. Will we learn a better way than Noah’s to preserve human communities and nonhuman diversity? What would a better way look like?

If Cohen and Yates’s wonderfully erudite, digressive, and imaginative journey does not quite answer that question, it may be because it’s not quite answerable, at least not yet. The kaleidoscope of ark-stories this brilliant book leaves us with is less sleek ship of a survival than an expansive, encrusted, not quite seaworthy tub, filled with stowaways, riven by strife, bound by love, about to founder but perhaps able to keep some creatures afloat. Until the next time the waters rise…