I started reading the novels of South African writer J.M. Coetzee back in 1986, on the suggestion of my then-prof Paul Auster. I started, I’m pretty sure, with Waiting for the Barbarians (1980), but I quickly devoured all the austere, slim, brilliant novels available. In 1988, I wrote a long undergraduate essay on the five novels from Dusklands (1984) and Foe (1986), in which I argued that Coetzee sought to craft a “middle space” between collaboration with an oppressive regime and active revolution. At the core of this ambitious if somewhat overwrought essay was the title figure of LIfe and Times of Michael K, for which Coetzee won the first of his two Booker prizes in 1983.

Even now, ten more novels and three fiction-ish autobiographies later, I think of Michael K as the core figure of Coetzee’s literary imagination. Arguments could be made for Elizabeth Costello, the Jesus figure in his recent trilogy, and two creepy exemplars of moral failure and complicity, the Magistrate in Waiting for the Barbarians and David Lurie in Disgrace – but I’m on team Michael K.

The postcolonial poet and critic Edouard Glissant celebrates the “right to opacity” for all humans, and I know few more strangely moving monuments to opacity than Michael K. That’s why I was intrigued to see his story staged with the title figure as a half-sized human-shaped puppet, designed by South Africa’s Handspring Puppet Company (famous for War Horse) and manipulated on stage by three puppeteers. Michael K is not the only mechanical figure in the story, which includes a variety of humans as well as puppet-renditions of his mother Anna K and (amazingly) a unlucky goat that Michael K encounters in the karoo in rural South African. But it’s Michael K, with his hare lip and awkward stare, who transfixes.

The novel opens with the hero’s birth, his hare lip, and his mother’s instinctive revulsion at “the mouth that would not close” (3). Video projection close-ups help the audience see this feature on the Handspring puppet. His deformity excludes Michael K from most communities, including a noisy and evocatively-staged failure to breastfeed as a newborn. The awkwardness of the puppet’s motions, and the need for multiple human handlers to operate the figure, perform the hero’s alienation more powerfully, I think, than any human actor could. Michael K is human, but he’s not. He needs connection, but also rejects it. The elaborate stagings of his basic bodily actions – eating, sleeping, walking, climbing a fence to escape a work camp – become a series of trials in physical over-coming, straining into being-in-the-world, just barely finding a way into an environment.

In the program notes, Coetzee describes himself as an “environmentalist” who has also won some literary prizes (two Bookers and a Nobel). The video projections of the area around Prince Albert in the karoo, where Michael K attempts to take his mother, and then later brings her ashes, show an arid and beautiful hardscape. To live in this place, amid the partly-sketched civil war and confining legal structures that are the story’s background, represents Michael K’s challenge and his partial achievement. “Perhaps it is enough,” he says to himself in a passage that the play did not quote, “to be out of the camps, out of all the camps at the same time” (182). Coetzee’s character is notoriously opaque in his racial classification, though at one place in the text he is identified as a CM – presumably “Coloured Male,” in the racial structures of the apartheid state. (The catalogers also get his name wrong, though, so maybe they don’t know everything.) The puppet’s soft brown skin matches this catch-all category, not White nor Black nor Indian. But it’s the movements of this Michael K that represent his refusal to enter into categories, into human orders, into the social world. As a not-entirely-human, Michael K endures to the side of history.

The final passage of the novel contains one of two phrases from Coetzee that float around in my imagination, surfacing at odd times. Unlike the devastatingly bleak final lines of Disgrace, which also circulate in my mind, the end of Life and Times of Michael K voices a minimalist utopian strain, something like what the narrator of In the Heart of the Country (1977) disparagingly calls “sweet closing plangencies” (139). But like the actors on stage last night, I tend to think that Coetzee mostly means it this time. He describes Michael K returning to the damaged well on his mother’s abandoned farm –

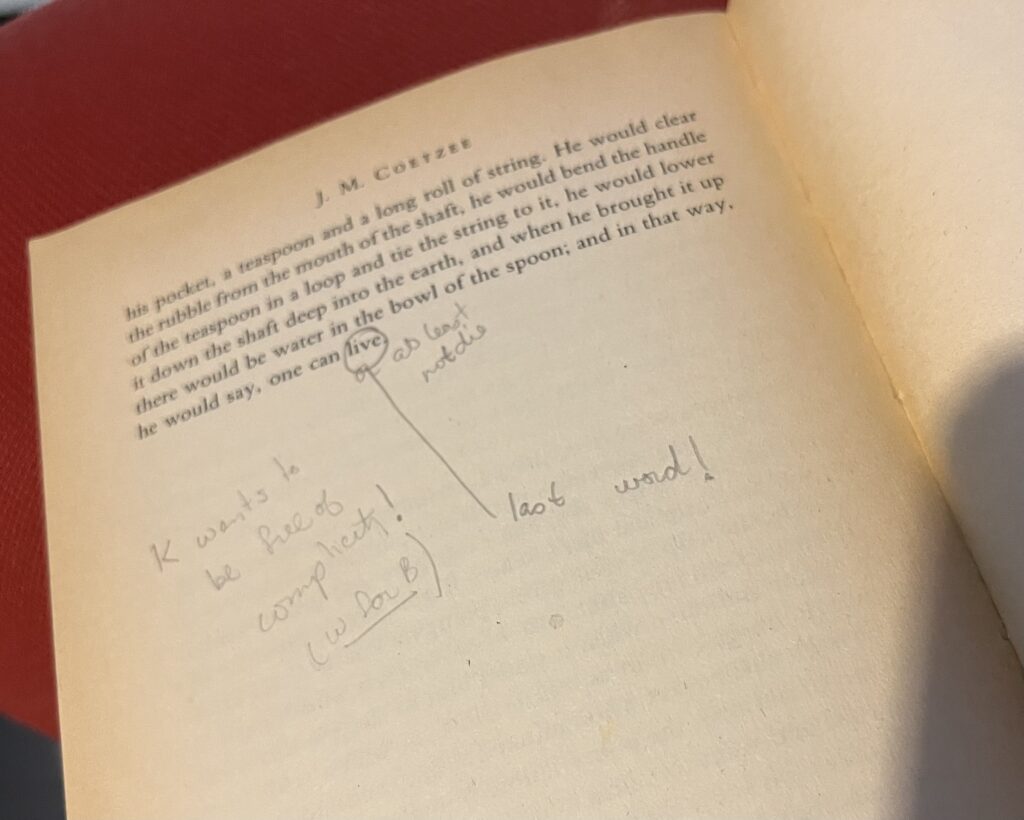

He would clear the rubble from the mouth of the shaft, he would bend the handle of the teaspoon in a loop and tie the string to it, he would lower it down the shaft deep into the earth, and when he brought it up there would be water in the bowl of the spoon; and in that way, he would say, one can live.

Life and Times of Michael K (184)

The caveats are all there – the absurdity of drinking-by-spoon, the abstraction of “one,” the repeated counterfactual “woulds” – but the novel ends with the word “live.” Looking at my three-decade-plus old pencil notes on this page, I see that undergrad-me I circled the word “live” – “last word!” my notes read. “At least not die.”

On stage at St. Ann’s, these rousing words were followed by lowering the puppet-body onto a red cloth folding it around him, and holding the motionless Michael K one last time. An amazing, moving, strange moment of theatrical magic.

Get to St Ann’s in Brooklyn before Dec 23 if you can!