Man thinks, ’cause he rules the earth, he can do with it as he please,

And if things don’t change soon, he will

Bob Dylan, “License to Kill” (1983)

Who gets a license to kill? To which individuals do we extend permission to commit violence, in the name of the state or of justice, or sometimes just to please an eager audience? What does our apparently endless capacity to consume images and representations of violence say about ourselves?

These were the questions on my mind as I squeezed into a balcony seat at the Longacre Theater on Broadway last Saturday afternoon to see one of the final preview performances of Sam Gold’s new production of Macbeth. This production, full of Gold’s usual creativity, was dominated by its stars, Daniel Craig as Macbeth and Ruth Negga as Lady Macbeth. Craig’s presence on stage presented three different ways to think about the license to kill – through the figure of Macbeth the ambitious regicide, through Agent 007 the state-sponsored assassin, and through Bob Dylan’s 1983 song. The truth of the show, as I had expected, was that Ruth Negga’s performance generated the theatrical high point. But Craig’s brooding presence, his familiar physicality, provided a visual, tactile symbol of how our culture thinks about masculinity, violence, and sex appeal. Much as I might want to refuse to grant the license, it’s hard to deny it in performance.

Dylan’s song “License to Kill” appeared in 1983 on the Infidels album that represented one of many come-back moments in the long career of America’s only living Nobel laureate in literature. Better known now as Dylan’s return to secular music after three evangelical albums, I remember Infidels as the sound track to my junior year in high school. The song “License to Kill” doesn’t overtly refer to the British secret service agent invented by Ian Fleming and popularized on the big screen since the early 1960s, but I find it hard to imagine Dylan, magpie repurposer of pop culture, wasn’t thinking about James Bond. The song attacks the killer-hero who “worships at an altar of a stagnant pool, / and when he sees his reflection, is fulfilled.” Narcissism seems a vice common to both 007 and Macbeth. Dylan’s penultimate stanza extends the accusation: “Oh, man is opposed to fair play / He wants it all and he wants it his way.” The license to kill includes ambition, a will to power, and a capacity for violence. These are the things that rule and ruin the world.

At least in the preview I saw, it took Craig a few scenes to warm up to that level of force and menace. He seemed a tad confused by the Weird Sisters, who were presented casually, three folks in hoodies dicing up vegetables for a stew, unlike many other versions of them that I’ve seen on stage or screen. But when Craig stood downstage for the soliloquy in which Macbeth debates the murder he and his wife had planned, he came into his own. His compact posture, coiled-spring poise, and visible capacity for violence devoured our attention:

If ’twere done, when ’tis done, ’twere well

It were done quickly…

1.7.1-2

I don’t always love seeing movie stars gobble up all the big Shakespeare roles on stage, but it was impossible to read that moment outside of Craig’s five films and fifteen years as Agent 007. Our eyes have been trained to read him through his capacity for sudden murder. The urgency of Macbeth’s language, his desperate need to “jump the life to come” (1.7.7), surrender to “vaulting ambition, which o’erleaps itself / And falls on th’other” (1.7.27-28), operated in that moment through the long cultural shadow of James Bond.

Shakespeare’s play, among other things, clearly intends to explore how the world appears to a man of violence. Even before we see him onstage, we’re told that Macbeth has “unseamed [his foe] from the knave to the chops” (1.2.22). He has a particular intimacy with killing, as the name “Bellona’s bridegroom” (1.2.55) suggests. For millions of movie theater-goers who don’t shell out Broadway prices for Shakespeare, the name “James Bond” conjures comparable feelings of power, sexuality, and ruthlessness.

Both killers are also lovers, though the new-partner-in-every-film progress that Bond has made over the decades contrasts sharply with Macbeth’s marriage. I always feel, watching this play, that the gradual separation of the married couple after the banquet scene (3.4) represents the emotional cost that both lovers will later pay in blood. Their early intimacy is horrific and gruesome, but I always miss it. (Probably my favorite of many good productions I’ve seen over the years was by the English troupe Cheek by Jowl; they hit the love plot hard.)

Ruth Negga, who played one of the most vibrant Hamlet’s I’ve seen just before Covid closed the theaters, was brilliant as Lady Macbeth. While I wasn’t certain that she and Craig matched themselves perfectly with each other in the early scenes between them, she equalled, or maybe exceeded, his intensity of focus. Her show-stopper, and the most emotionally powerful moment in the show for me, was the “Out, damned spot” speech in 5.1. Early on in Covid I read someplace that this speech takes about 20 seconds to recite, which meant that for many long months after March 2020, I washed my hands slowly to its awkward rhythms —

Out, damned spot: out, I say. One, two. When then tis time to do’t. Hell is murky. Fie, my lord, fie, a soldier, and afeared? What need we fear? Who knows it when none can call our power to account? Yet who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?

5.1.35-40

Negga’s sleepwalking performance of these well-known lines brought out their disjunction and physicality. While the doctor and nurse watched, gasping at the crime she revealed, Lady Macbeth’s isolation controlled the stage. She wasn’t as fast-moving as she had been while in antic mode as Hamlet, but if anything the sleepy compression made the emotional force stronger. I hope she gets a lot more big roles, both male and female parts!

Thinking about Ruth Negga’s brilliance brings me back to Dylan’s song, which alternates between attacks on the man with the license to kill and appeals to the “woman, on my block” who laments his violence. As with some other songs on Infidels, the conservative gender roles – man the killer, woman the healer – feel crude. But the juxtaposition of play and song also recalled for me a scene from Daniel Craig’s first Bond film, Casino Royale (2006), which explicitly framed Bond as one-upping Macbeth. After a bloody shootout with some bad guys, Bond’s love interest, Vesper, sits disconsolate in the shower, trying in vain to scrub blood off her fingers. The secret agent joins her, as Macbeth never joins his mad wife. Bond kisses the blood from each finger, as Macbeth never even tries to do. Vesper will die at the end of the film, after ambiguously betraying Bond, and the closing line that the film cribs from Fleming’s original 1953 novel – “The job is done, and the bitch is dead” — rings hollow in the face of the hero’s emotional devastation, a despair still visible in the opening scenes of Craig’s final Bond performance, No Time to Die (2021). In this movie, and perhaps throughout the five Daniel Craig Bond films, 007 became a Macbeth with at least some kind of moral center, as well as some kind of allegiance to queen and country. Or at least that was part of the story.

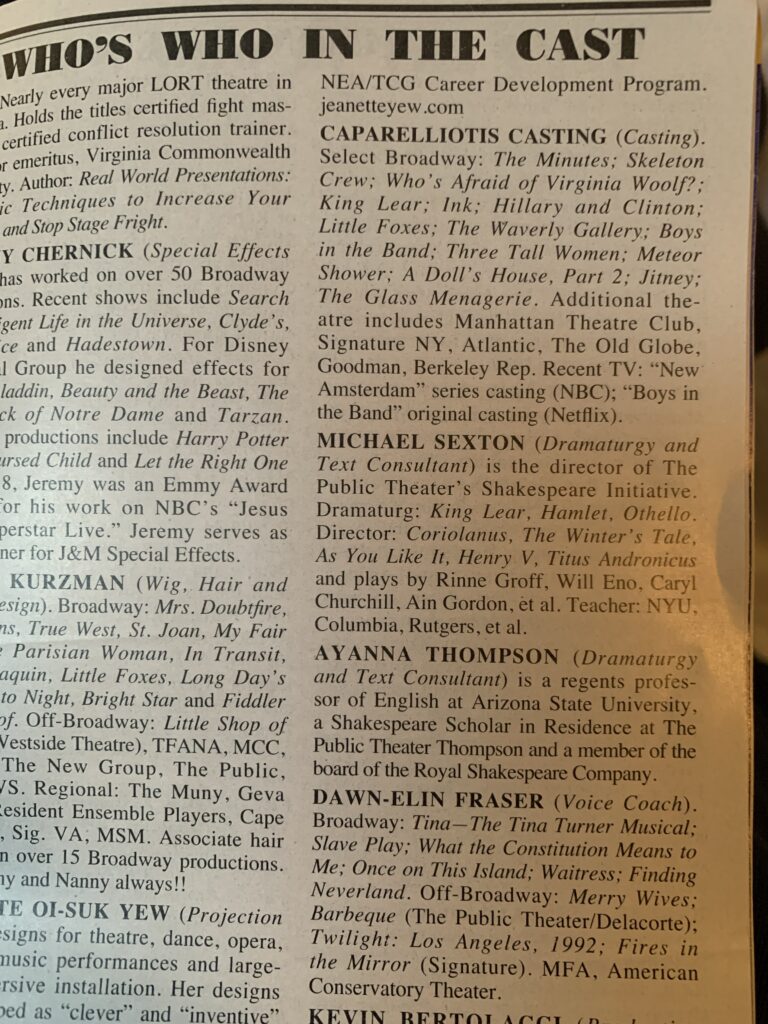

The last few things I’ll mention in this short & impressionistic review, which I’m sketching out on the day after the performance but won’t post until the play officially opens on 4/28, is the powerfully performed sense of community among the cast. That solidarity pushed back in interesting ways against the solitude of the two stars. From my vantage on the balcony I could glimpse backstage to watch the actors hugging in preparation for the opening curtain. In the liminal time just before the show started, the witches wandered back and forth with kitchen knives and vegetables; more exotic ingredients would come later. The production, directed by Gold in consultation with two brilliant dramaturgs, Ayanna Thompson and Michael Sexton, present the cast as a fluid unity, distinctly diverse, and not just in race and gender – Asia Kate Dillon, who played Malcolm, is non-binary, and Michael Patrick Thornton, who played Lennox, is disabled and uses a wheelchair. The original music, including a haunting final song, was composed by the disabled violinist and folk singer Gaelynn Lea. In an informal prelude that was also part birthday celebration – I saw the play on Big Will’s 458th birthday – Thornton wheeled himself to center stage to tell stories about King James’s love for witches, and also about our love for Shakespeare. Playing the part of Lennox, and also gobbling up some of Ross’s part, Thornton maintained a special intimacy with the audience.

[Some staging spoilers follow!]

There were not quite as many of the aggressive stage coups I’ve come to associate with Gold’s directing — I’ve seen his great Hamlet and his a bit less great Lear in the past half-dozen years — but probably the most striking moment saw Paul Lazar’s King Duncan, just after being murdered, slough off his bloody belly-pillow and slouch forward to perform the part of the Porter. It was a great surprise and bit of meta-theater, and it made me think about the way in which Lazar’s King had all along been playing for more laughs that I would expect from the part. Is there something comic about the good King who the Tyrant murders? I suspect so – I’ve got a blue humanities reading of the play in which Duncan, and to some extent his son Malcolm, represent a green ecology of agriculture and growth, against which the Macbeths represent blue oceanic violence, velocity, and tyranny. By making Duncan not just the planter of seeds but a cracker of jokes, Gold opened up that reading – perhaps wider than I want it open?

The final moment of the play calls for the tyrant’s bloody head to be displayed to the audience. Perhaps knowing that the fans don’t want to see that happen to the movie star we’ve paid to see, Gold closed out his production with a nod toward Craig’s head and a gorgeous communal folk song shared by the entire cast, sitting together onstage. It was a strange, compelling, counter-intuitive moment. There’s a way in which performances of Macbeth can feel like iterations of a ritual. Several film versions, including Roman Polanski’s in 1971 and Joel Coen’s in 2021, end with hints that the cycle could start again soon. Gaelynn Lea’s folk song, the chorus of which I think went, “It’s not perfect” (or maybe “I’m not perfect”?) brought the shattered kingdom together. The meta-theatrical emphasis on continuity and community fit together the reconstituted kingdom. The long-term prophecy that Banquo’s heirs will rule Scotland points to Shakespeare’s own monarch, King James, ruler of both Scotland and England. But in the present of the play, Malcolm – not an ancestor of James Stuart – reigns, the “butcher and his fiend-like queen” (5.9.35) are dead, and “the time is free” (5.9.21). Is that complex mixture of fictional and historical pasts, presents, and futures what “it’s not perfect” is meant to recall?

It was great to be back in the theater! Still some (expensive) tickets available through July 10.