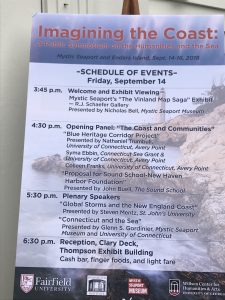

Day 1 at the Greenmanville Church

I’m back home after a glorious two days at the Imagining the Coast symposium organized by Nels Pearson and the Fairfield Humanities Institute. I come away buzzing with ideas about coastal retreat and the need to face our shared history of human and environmental injustice. Turning it over, I’m mulling two semi-inverted questions about coastal ecologies and societies:

- How will it be possible for us to retreat from the over-development that puts coastal areas at risk while still facing and learning from the sea ?

- Can we face our shared history of prejudice and injustice while also remaking the cultural and physical systems we have inherited?

In other words — can we learn from our engagement with our coasts and oceans? Can we transform ourselves into that combination of unlike things Melville calls “terraqueous”? How might we swim in these coastal waters?

The Vinland Map (a forgery)

At the end of the event some eloquent answers came from Barbara Hurd, who at sunset on Saturday afternoon on Enders Island, as we watched a three-masted sloop disappear behind the silhouette of Fisher’s Island, read from her dazzling memoir Walking the Wrack Line while also getting to the heart of the matter.

“We live in more than one world at a time,” she insisted. We need the project of attention — which is the project of art — to help us to “glide easily between the scales.”

In listening to her in golden afternoon light pronounce the dual imperatives to embrace all the scales (physical, temporal, human) and to cultivate attention as the engine that drives language and narrative, I found myself more hopeful than I often am at environmental events. More hopeful, also, than I allowed myself to be after my own talk on Atlantic hurricanes past and present.

So many riches in this dense and friend-filled weekend! I’ll skate through some highlights, with apologies in advance for mis-statements and omissions —

Nicholas Bell of Mystic Seaport opened the weekend by leading us through Mystic’s current exhibition on the Vinland Map, a forgery that Yale University was attacked for exhibiting as truth in 1965, though one of the ironies of the story is that while the map has been conclusively exposed as a fake, the underlying claim that Viking traveled to the Americas around 1000 CE — the fact that outraged Italian-Americans just before Columbus Day in 1965 when Yale unveiled the map — seems unquestionably true. There’s a lesson in the Vinland Map story about secrecy and the hubris of elite institutions, and also one about why certain kinds of evidence — maps you can photograph — count for more than, say, Viking artifacts found in archeological digs.

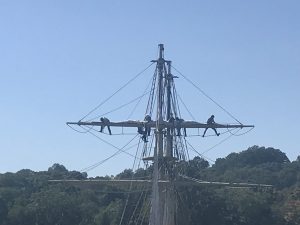

Working aloft on the Joseph Conrad

The first panel that afternoon include information about the fantastic Blue Heritage Corridor Project, a work-in-progress presented by Nat Trumbell, Syma Ebbin, and the Maritime Studies faculty at UConn Avery Point, and a presentation by John Buell about the Sound School in New Haven, where my kids used to go to summer camp. It turns out, not surprisingly I suppose, that I share some common ground (and water) with the folks from the Sound School.

Next I shared a plenary stage with my long-ago teacher Glenn Gordinier of Mystic seaport. I talked about American hurricanes and the violent weather of the Western Hemisphere, and I used the disorienting experiences of early modern Europeans encountering this weather system for the first time as a way to imagine our own era of increasingly unfamiliar storms. Glenn talked about the long history of Connecticut and the sea, starting with the last Ice Age.

After a festive dinner including oysters and local craft beer, the next morning started early with a panel on Long Island Sound featuring talks by Jason Mancini of Connecticut Humanities on Native American mariners, Glenn Gordinier (again!) on Yankee whalers, and Andrew Kahrl of UVA with a close-to-home discussion of coastal development in Shoreline CT towns after hurricanes Sandy and Irene.

(One personal undersong of this short trip was me getting lost driving around Mystic with a car full of visiting scholars from Ireland, England, and Spain. I spent six weeks in Mystic as an NEH fellow in 2006, came back regularly over the next couple years to work on the demo squad, guest-taught for the Williams-Mystic program, and brought my then-young kids to the Seaport and Aquarium — so I think of myself as someone who knows my way around the area. But I’ve not been back much in the past half-dozen years, and to be honest I was sometimes distracted by coastal academic chatter. So my car took some roundabout routes. But the good news was that we discovered the new home of my long-ago favorite breakfast spot, Kitchen Little, which is now out by the harbor on Mason’s Island. The Portuguese Fisherman scramble with chorizo, just as I remember it from 2006, tempted me into sliding off the vegetarian wagon just for one meal.)

During a very busy Saturday I heard some concurrent panels featuring Kurt Schlichting of Fairfield U on the Manhattan Waterfront; Richard Greenwald, also from Fairfield, on the containerization revolution and the New York’s longshoreman’s union’s connections to the shift of the port to Newark, NJ; Mary Murphy of Fairfield on Newport; Shawn Driscoll of Becker College on Nantucket separatism during the War of 1812; Ken Reeds from Salem State U on Kipling’s poetics of (American) empire); and Elizabeth Rose from the Fairfield Museum on their great exhibition on Rising Tides on the CT coast.

The Featured Panel in the afternoon brought together three stunning papers about Atlantic connections. Hester Blum of Penn State, a leader in oceanic literary studies, presented her research on Inuits who were buried in Groton, CT, in the 19c in a way that demonstrated both the powerful local New England connections of some well-traveled Inuits and also their continued longing for the land of ice. Nicholas Allen, who runs the Wilson Center for the Humanities at the U of Georgia, spoke compellingly about an Irish revolutionary whose portraits of his home superimposed themselves onto American landscapes from Taos to Stonington, CT. John Brannigan, who’s recently been directing an interdisciplinary Coastal project at University College Dublin, juxtaposed nuclear power plants in Connecticut and Cambria and showed how these environments reflect and are reflected in site-specific poetry. All three papers wrestled with how oceanic connections allows us to think plurality and human individuality at the same time. All coasts are particular and the tidal circulation of winds and currents makes coastal experiences at least partly mobile and shared.

Our final shared event Saturday was Barbara Hurd’s keynote about scales of time and poetic attention, wrack lines and artistic visions. After so many dense academic papers, it was a pleasure to hear from a writer whose directness squarely faced the challenge of loving and attending to our beautiful broken world as it breaks and dazzles us and our communities.

I’ll be thinking about what I learned this weekend at Mystic and Enders Island for a long time. I’ll also be thinking about what Barbara Hurd said to me when I thanked her for her words, and for bringing together the challenge of thinking across many scales with the imperative to focus our attention.”I think swimming has something to do with it,” she said.

I said that I think so, too.

View from Enders Island

Thanks to the Fairfield University Humanities Institute, Mystic Seaport and Enders Island, CT Humanities, the SeaGrant Program, and all the interlocutors of the weekend! I look forward to seeing these thoughts and words continue their circulations.

Another view from Enders