When I was a teenager, just about my son’s age now, I churned through a bunch of the big Russian doorstopper novels: Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Gogol. (I didn’t get to Bulgakov until much later.) What I remember most about The Brothers Karamazov was the humor: a goofy, earnest melodrama that finally turned into a near-spoof of a trial scene, in which the unsuccessful defense lawyer’s arguments on behalf of the (technically innocent but morally guilty) Dmitri rotated around some quite silly chapter titles: “There was no money, There was no robbery” (4.12.11) and “And there was no murder either” (4.12.12).

When I was a teenager, just about my son’s age now, I churned through a bunch of the big Russian doorstopper novels: Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Gogol. (I didn’t get to Bulgakov until much later.) What I remember most about The Brothers Karamazov was the humor: a goofy, earnest melodrama that finally turned into a near-spoof of a trial scene, in which the unsuccessful defense lawyer’s arguments on behalf of the (technically innocent but morally guilty) Dmitri rotated around some quite silly chapter titles: “There was no money, There was no robbery” (4.12.11) and “And there was no murder either” (4.12.12).

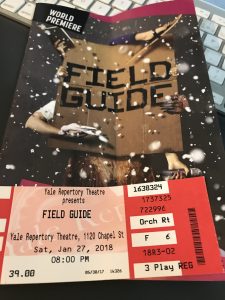

So I should have been pretty well suited to see Rude Mech‘s world premiere of “Field Guide,” a theatrical transposition of the novel that features bear costumes, stand-up comedy, and the Grand Inquistor exchange taking place in a hot tub. Why didn’t I dig it?

I saw the show on the second night of previews, and maybe it’ll tighten up as they go forward. But the pacing felt off to me: Dostoyevsky overflows with melodrama and intensity and excess, but the comic aesthetic here was understated, and sometimes oddly silent. The various stand-up routines, including the one performed in a bear costume, fell flat, at least to me, not only because the only really funny line was the topical one about “how many Russian bears does it take to fix a U.S. Presidential election?” The real problem, for me at least, was flagging energy: the novel’s about existential uncertainty, but more than anything it loves to speak, to argue, to polemicize!

There were some decent performances, including Thomas Graves as a commanding Ivan who introduced himself by quoting Kant, Hegel, and Nietzsche. Lana Lesley’s Dmitri showed real emotion when pleading with the patriarch for money, but Lowell Bartholomee as big daddy Fyodor K. was oddly too charismatic, or perhaps too well-loved by the cast and performers, to show himself as the monster who all of his sons want to disavow if not murder. Mari Akita’s Aloysha can perhaps be forgiven for not accomplishing the impossible task of finding a way to stage spiritual longing, but the insertion of a solo dance routine in response to Father Zozima’s death, while accomplished, felt unconnected to the bulk of the action.

It’s can’t be easy to compress an 800-page novel into 90 minutes of theater, and the Rude Mechs’s announced theory — that The Brothers K can serve as a “field guide for living” — might not make it any easier. I love ambitious experimental theater, and I’ve seen at least one brilliant staging of a Russian masterwork (Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita, also at Yale Rep in 2014). Maybe this show will struggle into coherence in performance?

Toward the show’s end, when Dmitri has been convicted and sent to Siberia, the remaining living family members plus the dead Fyodor sat together and passed around a fat copy of the novel. Ivan, Katya, and Alyosha read short extracts. It made me wonder if it would have been possible fully to translate Dostoyevsky’s mad genius into physical theater. What might that look like? Another time, perhaps.