On my last day in rural northern New South Wales, while I was bush-walking down a dusty path scattered with anthills in the slightly smoke-flavored air, I walked by a red-bellied blacksnake curled along the side of the path. I was the second walker in our group, which put me in the at-risk position: the first walker wakes the snake, the second gets him agitated. But I passed in silent oblivion, thinking about bush fires and the Myall Creek Massacre and the brilliant papers and panels at the University of New England conference on “Compassion: a Timely Feeling,” which had take place over the previous two days. Was the invisible-to-me red-belly an allegory? A symbol of something? Just, as we say, another snake in the grass?

It’s hard to parse what the snake means, but I had a great whirlwind visit to Armidale.

I came straight from the plane to the first keynote, a rich exploration of the intellectual genealogy of compassion in Britain from the late Middle Ages through the eighteenth-century. Katie Barclay, who teaches at the University of Adelaide in South Australia but whose vowels reveal her Scottish heritage, spoke about “neighborly love” before and during the Enlightenment, with special attention to what she calls “emotion management” as a key task for individuals and social bodies. She’s a longtime employee of the “History of Emotions” Centre of Excellence in Australia, and the depth of her knowledge and thinking on this important subject was on display.

I can’t gather together all of the nine panels and 3 keynotes, especially not while wanting also to talk also about our bus tour of the Australian bush on Saturday. So my blog-recap will skate between talks and tours, moving now from Katie’s deep archival research to first stop on our drive, the living archive of a Chinese emporium in Tingha, NSW, which has been converted into a museum after the family closed the business. The shop thrived during the tin boom in the nineteenth century. When the family finally abandoned the shop in the 1990s, the town had not quite ghosted but was just a whisp of its boom. The emporium turned museum was filled with old and new items, including whatever goods had not sold in the last years of operation still on their shelves. It was a slightly eerie look at social change and the human history of extraction in Australia.

In between Th afternoon and Friday at the conference, we heard a dazzling array of transdisciplinary responses to compassion, from David Holmes’s description of his Centre’s work in Climate Change Communication to Renee Mickelburgh’s “everyday environmentalism” of garden narratives, Deb Anderson on the “wet tropics” of rural Queensland, and other papers on the speculative reach of cli fi utopias, surfing and “care of the soul,” and a series of talks about climate activism, much of which described Australian contexts that were largely new to me.

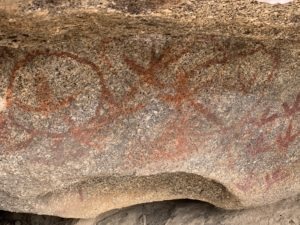

A highlight of our long drive into the bush on Saturday was visiting the Myall Creek Massacre memorial. We walked a short self-guided loop with plaques explaining the Aboriginal heritage of the site as well as the massacre of 1838. The Myall Creek event was just one point in the wave of anti-indigenous criminal violence that accompanied the colonial settlement of Australia (as well as, of course, the settlement of the Americas). It’s a powerful feeling to be a descendent of colonizers standing in front of a memorial that protests the crimes of white Europeans. I could not help but think that the bush flies, dive-bombing incessantly inside my sunglasses as I walked along the path, were somehow spirits of the land, reminding me of my own alien-ness and complicity. I’m glad to have seen this place, and to have honored, in the resonant phrase that I heard at almost every talk in Australia, “Elders past, present, and emerging.”

My own talk on Friday morning at UNE was about (what else?) the oceanic feeling. I offered basically two ideas. First, I suggested that compassion, much as we love it, can also be an oppressive social demand; my example was one of English lit’s most horrid mother-monsters, Mrs Bennett from Pride and Prejudice. “Have you no compassion on my nerves?” she bullies her husband in the first chapter. Second, I hazarded the idea that re-routing compassion in nonhuman and oceanic directions might open up new ways to live amongst rising Anthropocene seas. I had a variety of examples for this second move, from Allan Sekula to Chris Connery to Luce Irigary, but the jumping-off image was Don Quixote looking at the ocean for the first time, upon arriving in Barcelona late in Part II. Compassion, it seems, makes me think of novels.

The pregame breakfast before the bush tour on Saturday was Jennifer Mae Hamilton’s “Community Weathering Station,” a pop-up water activism and theorizing site that she’s been curating in dialogue with the painful drought around Armindale. She’s asking everyone, including herself, to reflect on how this dry community feels about water, and about the town’s dependence on the weather. It’s a great, engaging, humanizing project that I hope to hear more about. I’ve known Jen’s brilliant work for several years, and it was a treat to meet her in person at last.

Delia Falconer’s closing plenary at the conference took up the question she also addressed in a lovely essay, “Signs and Wonders,” in the Sydney Review of Books. She explored how creative writers might be able to respond to our newly dynamic climate. In the talk she responded to James Wood’s hand-wringing about fiction writers’ supposedly failed responses to 9/11. I very much agree with where she ended up — that the fictional imagination needs to confront environmental strangeness both directly and obliquely, and that stories can teach us things we don’t know that we need to know.

The shock of Armidale’s dry heat struck me all the more palpably when I arrived on Sunday to Sydney’s humidity and abundant swimming locations. Rural New South Wales isn’t obviously amenable to my water-research in the same way that Sydney is. But I’m very pleased to have had the opportunity to see it for myself and not be confined only to urban Australia.

Thanks to Diana Barnes for the invitation, and everyone in Armidale for their hospitality!