Isabella and her brother Claudio

The last dance hit the hardest. After a dizzying, painful, intense intermissionless two hours, she followed his lead. At first, when Isabella received the now-undisguised Duke’s marital offer, she seemed, as in some other recent productions I’ve seen, nonplussed and not interested. Anna Vardevanian, who gave a strong and sometimes enraged performance as the wanna-be nun, seemed a bit stunned. But I knew it was a bad sign when she let her long black hair down out of the nun’s habit she’d worn throughout the play. In the final tableau, she awkwardly folded herself into dance position. The Duke embraced her with the same creepy paternalism that Angelo had cooed when he assaulted her in the second interview scene (2.4). The music carried their bodies together. They skipped around the stage in the same arcs that Juliet and Claudio and Marianna and Angelo had just traced. Everything was in order. No freedom in Vienna, or in the contemporary Russia that it represents in this brilliant production.

One from inside the program

The only one to get away might have been Barnadine, the drunk convict played brilliantly by Igor Teplov. Despite his small role, Teplov got lots of stage time, since the full thirteen cast members spent most of the evening all on stage together, with anyone not speaking in a given scene watching on one side, or zooming about in a group to mark scene changes. When the group was together, Teplov, tall and striking, often stood at the head, in a kind of implicit leadership position. When he refused execution (4.3) and again when he was pardoned by the Duke (5.1), Barnadine staged the direct resistance no one else could quite manage. He struck the Duke-as-friar in the prison scene, and then he was the only one who could escape off-stage in the middle of the Duke’s re-assertion of political control (5.1). It was good to see him get loose, but I wished he’d taken Isabella with him.

The production I saw this past Tuesday night, at BAM for only a week, restaged the legendary collaboration between Cheek by Jowl, one of my favorite London-based companies, with Moscow’s Pushkin Theatre. The Russian-language production debuted in Moscow in 2013, played London in 2015, and is in the US for the first time this year [Correction: it played Chicago in 2016, and in Brooklyn only this week] in our second year of #metoo. Watching it, I wondered if, in these raw post-Kavanaugh & pre-mid-term days in the US, it’s possible to stomach this tale of hypocrisy, power, and women who suffer. It’s not the kind of show that leaves you happy.

Isabella inside the program

Go to your bosom / Knock there, and ask your heart what it doth know / That’s like my brother’s fault (2.2)

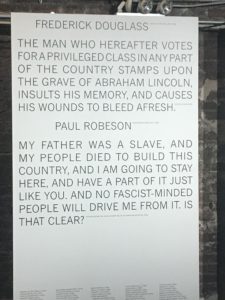

Inside the lobby at the Harvey Theater