I’m very sorry not to be able to get to this great-looking conference in a few weeks in London. I am looking forward to hearing all about it, and to participating in the “Renaissance Routes” research network that the final session aims to propose.

I’m very sorry not to be able to get to this great-looking conference in a few weeks in London. I am looking forward to hearing all about it, and to participating in the “Renaissance Routes” research network that the final session aims to propose.

Bloomsday 2012

What in water did Bloom, waterlover, drawer of water, watercarrier, returning to the range, admire?

Its universality: its democratic equality and constancy to its nature in seeking its own level: its vastness in the ocean of Mercator’s projection: its unplumbed profundity in the Sundam trench of the Pacific exceeding 8000 fathoms: the restlessness of its waves and surface particles visiting in turn all points of its seaboard: the independence of its units: the variability of states of sea: its hydrostatic quiescence in calm: its hydrokinetic turgidity in neap and spring tides: its sudsidence after devastation: its sterility in the circumpolar icecaps, arctic and antarctic: its climatic and commercial significance: its preponderance of 3 to 1 over the dry land of the globe: its indisputable hegemony extending in square leagues over all the region below the subequatorial of Capricorn: the multisector stability of its primeval basin: its luteofulvous bed: its capacity to dissolve and hold in solution all soluble substances including millions of tons of the most precious metals: its slow erosion of peninsulas and islands…

— Ithaca (17; p549)

Swimming the Chesapeake

For just a bit under 3 hours yesterday, between the spans of the Bay Bridge, I was Aquaman, Cap’n Metis, and Mr. Nemo. Just me, the water, and about 600 other swimmers.

Like all long swims, it was an attempt, partly successful, to maintain form inside formlessness. Not to impose my form on the moving water — no chance of that — but to insert my form-creating body into the Bay, finding my way through the repetitive churn of stroke after stroke, breathing mostly on the left but also on the right, kicking just enough to keep my body streamlined in the water. When the chop hits you in the mouth, or your stroke misses, it’s hard to return to form, but it’s only through form that you can make your way through the water.

I spent a lot of time thinking about currents. The swim started at 11:15 toward the end of the flood, which means I swam into the tide to get between the shadows of the bridge towers before turning across its current to start swimming east. At the end of the swim, when I ducked outside the bridge for the final 1/3 mile onto the Eastern Shore, the ebb pulled me hard southwards. To get out from under the shadow of the eastbound span, I just floated for 10 seconds and let the tide carry me.

I thought about literature, as I always do. Two lines in particular. First, Shakespeare:

whilst this machine is to him (Hamlet, 2.2)

That’s what I thought about myself as I noticed how automatic my stroke became, how little my mind seemed to control arms and legs. Breathing was a bit less mechanic; I had to chose to breath left or right, trying to balance in the sometimes choppy water and also judge my position by the bridge towers. “This machine” is the phrase the prince uses for his body in his love-letter to Ophelia; it’s what I felt like in the water.

Also —

mobilis in mobili (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea)

I thought about Nemo’s motto, moving inside mobility, and its paradoxes, esp late in the swim when I had to fight the current to keep myself inside the bridges.

Highlights of the course included two deep shipping channels, the larger of which I swam through at slack tide before I was too tired, at about mile two; two anchored paint barges the stuck their sterns into the course so that we had to detour around their anchor chains; and the sickly warmth of the last 500 yards in shallow, sheltered water leading up to the marina: it made me realize how much cleaner the moving water in the center channel had been. Plus by then I just wanted to get out.

Looking up at the bridge spans from the water made me think of Thoreau hearing the railroad whistle from Walden Pond (Ch 4). No separation from made-things even in the water. The Bay is still in many ways like it’s always been, but bridges and boats and hundreds of churning human bodies mark the water, even if the imprints don’t last.

My arms hurt and my back is sunburned — but what a great way to spend a Sunday in June!

The Great Chesapeake Bay Swim

Heading to Annapolis right now..

JCB Fellows 50th

I’m heading south on Amtrak now, after spending the last two days at the JCB Fellows Program 50th  Conference. I always love going back to Providence — as Ralph Bauer said during his talk yesterday afternoon, every time we one-time fellows walk back to Thayer St it feels like home. The conference itself was an odd and intriguing mix, mostly historians — my panel and Ralph’s were the only sessions chaired by literary scholars, and mine the only one with a substantial proportion of literary rather than historical folks on the panel. The keynotes, by Bernard Bailyn and Rolena Adorno, were really about the history of the JCB and the Brown family since the 18c, and also of the Fellows program since 1962. It’s great stuff to know about, esp. after collaborating with the JCB on the Hungry Ocean conference last year, but not the same as an academic conference that’s going to change the way you think and do your work.

Conference. I always love going back to Providence — as Ralph Bauer said during his talk yesterday afternoon, every time we one-time fellows walk back to Thayer St it feels like home. The conference itself was an odd and intriguing mix, mostly historians — my panel and Ralph’s were the only sessions chaired by literary scholars, and mine the only one with a substantial proportion of literary rather than historical folks on the panel. The keynotes, by Bernard Bailyn and Rolena Adorno, were really about the history of the JCB and the Brown family since the 18c, and also of the Fellows program since 1962. It’s great stuff to know about, esp. after collaborating with the JCB on the Hungry Ocean conference last year, but not the same as an academic conference that’s going to change the way you think and do your work.

My panel, Salt Water in the Archive, was great fun. We ran it as a real round table, with no one speaking for more than 4-5 minutes at a time, as we went three times round describing our favorite items from the collection, our most valued insights from current oceanic studies, and our hopes for its future. Some interesting paths opened up: Hester Blum sent me toward Gayatri Spivak’s argument for “planetarity” as an alternative to “globalization,” as outlined in her 2003 Death of a Discipline where she writes “I propose the planet to overwrite the globe” (72). While I’m not sure the planet/globe binary maps as precisely onto her political nexus as she might want, I do think that, as with Ursula Heise’s presumably related “sense of planet,” the oceanic, alien, and inhospitable element of our globe can best emphasize the scattered and disorienting nature of the global/planetary imagination.

Some other very good stuff by Mac Test in his Latourian reading of New World commodities in Old World economies, including his pointed reminder about the present of two Algonquin natives in Harriot’s house when he wrote his Brief and True Report of…Virginia. John Hattendorf reminded us that the AHA has recently added “maritime history” to its official list of categories; Mary Fuller mentioned several fascinating collaborative projects she’s working on with scientists at MIT; and Chris Pastore gave a fascinating glimpse of ecological and cultural boundaries of Naragannsat Bay in the late 17c. The Q&A was very lively and spilled us over the time; several people including Robert Foulke, who I was very happy to meet for the first time this weekend, wondered if we had any plans to expand maritime studies as a sub- or inter-discipline, and David Armitage had a wonderfully focused closing question about depth and the unfortunate tendency of maritime history to stay on, or near, the surface of the ocean.

There were quite a few strong talks in the part of the conference I could stay for, including some very interesting observations about comparative history in the Americas and several wonderful spculative talks & performances about early modern music and the European-Native encounter. I hadn’t known that some northern FL Indians apparently remembered for a generation or so a French hymn they had learned from a Huegenot colony that had been subsequently massacred by Spanish Catholics. Some very interesting methodological speculations about the early modern musical landscape also: many more performers, but much less music than our iPod-connected world.

It’s especially great always to see the JCB community, including many of my fellow Fellows from 2008-09, though not Vin Caretta alas, and the great curators and staff. Maureen O’Donnell sounds fired up for Hungry Ocean 2 in 2013 or 2014 — though I need to finish the book attached to the first conference first!

My Oceanic SAA

I’m rushing to get ready for a Maritime Humanities conference in Buzzards Bay and also copy-editing an essay for this summer’s PMLA, but oceanic thoughts from last weekend’s SAA in Boston are still churning. I’ve been beat to the blog by my medievalist guest, which isn’t really surprising, but there’s some treasure left down on that salty bottom. Let’s see if I can dive down to it.

I’m rushing to get ready for a Maritime Humanities conference in Buzzards Bay and also copy-editing an essay for this summer’s PMLA, but oceanic thoughts from last weekend’s SAA in Boston are still churning. I’ve been beat to the blog by my medievalist guest, which isn’t really surprising, but there’s some treasure left down on that salty bottom. Let’s see if I can dive down to it.

SAA seminars are among my favorite academic events. Pre-circulating the papers, which all seminars do, and exchanging responses beforehand, which most do, means that you come to the event already part of a dynamic exchange, and the trick is to move everything forward. The two hours’ traffic of the seminar needs to make contact with all the distinct projects but not get bogged down by re-hashing material we’ve already covered in our e-exchanges. I used personal introductions, a hand-out, and a parlor game.

When we introduced ourselves around the table I asked, at this risk of bringing sentiment into scholarly life (!), for personal connections to the sea. I’m fascinated by the stories that flowed forth, from paternal stories of the navy to assorted maritime engagements and adventures. I talked about open water swimming. It took a fair amount of time to get all these stories out, more than if we’d just given names & academic homes, but that quick dip into our imaginative oceans primed us to think personally about the academic material that followed.

The parlor game involved me giving each seminar member a maritime term or phrase that has entered common speech — “from stem to stern” “doldrums” “aloof” “the bitter end” — and asking each participant to smuggle that word into our discussions, at which point the word-smuggler would triumphantly cast the printed term into the center of the seminar table. We never got to part two of this exercise, reflecting on how these words might represent or capture the deep interplay of metaphor and technical reality in the way we talk about the sea, but it was great fun. It also helped us make transitions, which can be awkward at these things. I used my phrase, “back and fill,” to shift us out of autobiographical maritime reflections and into Carl Schmitt’s Anglo-centric vision of maritime empire.

The seminar outline offered to a few general questions — Schmitt and empire, Glissant and the beach, an assortment of oppositions including metis/intellect, beach/whirlpool, and surface/depth — to get ideas circulating without tying them too explicitly to specific papers. We concluded, perhaps too easily, that we don’t like neat oppositions, though I also wonder if the desire to connect or blur oppositions isn’t in its own way as oversimplifying as the binaries themselves. The trick may be finding a way to think meaningfullly about difference and connection at the same time.

My job when navigating the 13 great papers and fantastic contributions of two non-Shakespearean respondents was keeping us off rocky shores, so my notes on the seminar outline aren’t terribly coherent. Some great stuff about cultural differences across different ocean basins, esp the Med / Atlantic / Pacific, and also the fresh/salt/estuary relationship — what to call it? A binary plus one? One interesting thing about estuaries is that their salinity changes with the tide and also with wind and weather, so they are perfect places to interrogate the fresh/salt distinction. There’s a way, as I was thinking some time ago, that this distinction maps onto local/global concerns: all fresh water questions are basically local, while salt water circulates globally.

The question of Shakespeare as such, interestingly and perhaps reveallingly, never really came up. Plenty of papers took up non-Shax-y topics and authors, and several seminarians used Shakespeare as a stalking horse for big questions about theatricality or ecology or the historical changes that accompany early modernity. Jeffrey Cohen hid his Bard-o-skepticism until he wrote his blog posts, where he has generous things to say about the whole event.

After the seminar, the rest of SAA was a blur of bars & plenaries, not always in that order. I very much liked the primatology panel with Holly Dugan & Scott Maisano, and thought the Fri morning plenaries were a bit bland in their admiration of all things SAA. Or perhaps I’m just no longer used to closing the bar, which makes me a bit cranky at a 9 am lecture!

I’m especially grateful to my two guest-interlopers, Jeffrey Cohen and Joe Blackmore, whose contributions did what I’d hoped they would do, stretching our discussion chronologically and linguistically and imaginatively. All academic conferences, even international ones like SAA, tend toward in-group parochialism, esp when our shared subject so often gets claimed as “not of an age, but for all time.” The idea of the seminar was not really to substitute “ocean” for “Shakespeare” in an all-embracing way, but to seek out fluid metaphorics — flows instead of spaces — that might enable us to deal with vastness and distance in different ways.

So — a new big thing for Oceanic Shakespeares? I’m not sure yet. But certainly wide horizons and strong winds blowing.

Sea-Changes: A Maritime Humanities Conference

Next week in Buzzard’s Bay!

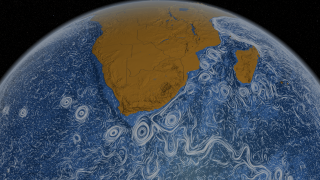

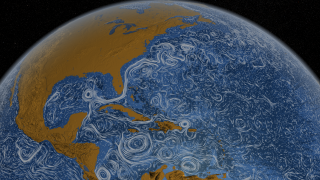

Perpetual Ocean

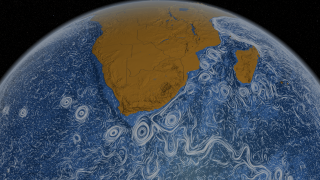

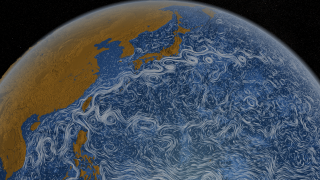

Some images from “Perpetual Ocean,” a fantastic video of ocean currents in circulation.

The Gulf Stream

Aguilas Current.

Kuroshio current.

Shipwreck is History

I’ve been thinking about shipwreck and other oceanic matters while reading the papers and responses for what looks like a great SAA seminar coming up in Boston in two weeks.

Since I have just a few free hours this week, I thought I might return to an article that’s not due until late April, but which sings the same salty chorus. This chapter will eventually be part of the intro to the shipwreck book, though I first wrote this material for a great conference at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich in fall 2010.

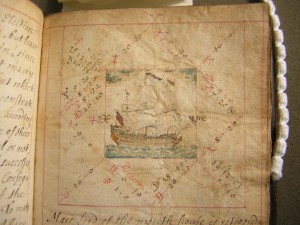

Here’s a little bit out of the beginning, which starts with this wonderful broadside, Richard Younge, The State of a Christian (1636) —

My Body is the Hull; the Keele my Back; my Neck the Stem; the Sides are my Ribbes; the Beames my Bones; my flesh the plankes; Gristles and ligaments are the Pintells and knee-timbers; Arteries, veines and sinews the serverall seames of the Ship; my blood is the ballast; my heart the principall hold; my stomack the Cooke-roome; my Liver the Cesterne; my Bowels the sinke; my Lungs the Bellows; my teeth the Chopping-knives; except you divide them, and then they are the 32 points of the Sea-card both agreeing in number…[i]

That manic voice insisting that human bodies and wooden ships occupy the same space is Richard Younge, from his broadsheet The State of a Christian (1636), a single-page work that also appears as a preface to Henry Mainwaring’s Sea-man’s Dictionary (1644). Its mania suggests how intensely and how physically oceanic experience stimulated the early modern imagination. Younge hurls human body parts, Christian souls, and nautical terms together. The resulting conceptual soup provides a frame through which to consider how shipwreck narratives reveal the dynamic meanings of the ocean in early modern English culture. Early modern shipwreck narratives were symbolic performances through which writers tested their own, and their culture’s, experiential knowledge of the ocean. Narratives of maritime disaster lay bare the tremendous practical and symbolic stress that the transoceanic turn created in English habits of orientation. Representations of shipwreck provide a resonant but unfamiliar model of cultural change in early modern English culture. To recast a celebrated modern poetic phrase about the sea, shipwreck is history.[ii]

[i] Richard Younge, “The State of a Christian, lively set forth by an Allegorie of a Shippe under Sayle,” appears as an introduction to Henry Mainwaring, The Sea-Man’s Dictionary, (London: John Bellamy, 1644), sigs. A3 – A3v. The passage is included in some copies of Younge’s The Victory of Patience (London: M. Allot, 1636). It was also published in a single sheet broadside as The State of a Christian (London, 1636).

[ii] I adapt Derek Walcott’s “Sea is History,” Selected Poems, Edward Baugh, ed., (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2007) 137.

Metis

I’m thinking about maritime know-how, metis, craft.

I’m thinking about maritime know-how, metis, craft.

My favorite of these words is Homer’s, metis, the particular kind of hand-knowledge and skill associated with Odysseus. It includes everything from sailing to boat- (and bed) building, not to mention fast talking. But it’s particularly associated with technical maritime skills and labor. It’s what Conrad calls “craft,” and what he thinks creates a bond among sailors. Some of the best writing I’ve seen on this topic comes in Margaret Cohen’s great recent book, The Novel and the Sea, which I e-reviewed on the Bookfish a little while ago, here. “Experience is better than knowledge” was the line I pulled out from the book, which Cohen took from Samuel Champlain’s manual on seamanship she does such great work with in her first chapter.

I’m wrestling with seamanlike metis, a set of tactics that improvisationally transform disorder into order, in a chapter of the book I’m writing on shipwreck from The Tempest through Robinson Crusoe. The metis chapter focuses on Jeremy Roch, a 17c mariner, amateur poet, and astrologer whose ms. journals are in the Caird Library at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich — a particularly wonderful place to do maritime research, by the way.

The picture above show’s an exploit Roch is espeically proud of: sailing in a open boat from Plymouth to London with only a boy and a dog, “one as good company as the other to me for any help I had need of,” as he notes.

Here’s a little snippet out of the current draft of the chapter —

Faced with disaster, sailors respond with work. Skilled, technical, hard to understand maritime labor becomes paramount in moments of crisis, which is why these episodes tend to fill with jargon. The Boatswain in The Tempest, whose lines provide the epigraphs for this chapter, provides a familiar example. His language interposes a host of sea-terms – yare, topsail, “room,” topmast, “bring her to try,” “main-course,” among others – alongside his resonant political and philosophic claims. While Shakespeare’s command of sea-terms was imperfect, he recognized the dramatic power of opaque, technical language in moments of crisis. The “cunning intelligence” and skill with technology that The Odyssey calls metis characterizes the core physical response of mariners to shipboard crisis. Metis is both a physical and an intellectual practice; it represents seamanlike labor and also an imaginatively-charged exploration of physical reality. As ships founder and rigging snaps, sailors struggle to maintain orderly forms of action and thought. The order-salvaging task of the sailor resembles the task of the shipwreck writer. Representing the jeitzteit crisis moment in poetic or descriptive language requires matching the physical labors of the mariner with the formal shaping of the writer. Performing metis requires hands, tools, and language.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- …

- 17

- Next Page »