I spent my second-breakfast visit to see Macbeth on Broadway in the company of a childhood friend who I don’t see nearly enough these days. After the show I was thinking about community, comedy, and a little about Terry Eagleton. In Eagleton’s famous (to Shax profs) reading of the play back in the 1980s, the witches are the heroines of the story, marginalized women who subvert established power structures with their riddling speech and multiple ambiguities. I often bring up this interpretation in class, in part to emphasize that the witches’ prophecies connect to British history, particularly in act 4, when they show Macbeth a line of kings stretching out to the crack of doom, perhaps reaching all the way to Shakespeare’s witch-obsessed king James I. I like to suggest to my students that the witches, in narrative past of the play’s sources, imagined the future of Stuart rule in England during which the play was first staged. The witches’ world, for Shakespeare and his audience, both reached deep into a mythic past, and also very much was happening right now.

Many of my students resist my efforts to rehabilitate the “secret, black, and midnight hags.” (The Broadway version, with its race-conscious casting influenced by the brilliant Ayanna Thompson’s dramaturgy, cut the word “black” in Macbeth’s line, at least last night. Most, but not all, the witches’ parts were played by Black actors.) It’s not easy to rehabilitate the eldritch forces of prophecy, either in Eagleton’s Marxist version or in the more communitarian vein that I sometimes try to suggest. But watching Macbeth last night at the Longacre Theatre on Broadway, I kept glimpsing hints in which the witches represent community, or perhaps even something close to comedy in the generic sense – not so much jokes, though there were more laugh lines in this production than in most versions of the Scottish play that I’ve seen, but instead as social cohesion in the face of disorder. Comic unity, I came to think as I weaved through crowded crosstown sidewalks after the show, was at the heart of Sam Gold’s typically inventive show.

It helped that I’d seen the production before, in previews on Big Will’s birthday in April. That meant I was prepared for the final tableau, in which after the good Mac[duff] kills the bad Mac[beth], the whole cast slumped against the back stage wall where they shared bowls of soup and listened to Bobbi Mackenzie’s lovely acapella singing of Gaelynn Lea’s folk song “Perfect,” the chorus of which provides a healing balm for the preceding bloodshed. “It’s not perfect,” she sings, presumably referring to all the tragic events but possibly also to the performance itself. It’s not perfect, the assembled cast seemed to say through their collective presence, but we’ve built it together.

The soup in the bowls, which even from the second row of the orchestra last night I couldn’t get a good look at, came from the witches kitchen. In that strange post-play moment, the shared food staged community, as the witches had in many of their scenes. The playbill lists five actors playing the “Coven” of witches, which expands the Three Sisters of Shakespeare’s text in what I took to be a very deliberate choice: the witch family comprised one of the biggest clans in the kingdom. When all the actors sat and supped together at the play’s end, the cast itself became integrated into the witches’ group. The play’s final unity was inside the world of the Weird Sisters. Notably, the final political pronouncement of the new King Malcolm, in which the Scottish thanes get promoted, or re-named, as (English? British?) earls, was omitted in this production. The happy performative family was the family of the imperfect speakers, the cooks, the future-knowers, the bubbles of earth and air.

Thinking about that moment of theatrical union as a fundamentally comic, in some bizarre way a Scottish version of the quadruple marriage and divine visitation that ends As You Like It, helped me make sense of the presence of comedy in the central action. Paul Lazar’s Duncan, as I noted in my April review, was more comic than I’ve ever seen the about to be murdered king. His shift from playing the role of dead Duncan to living Porter was artfully staged, and it reminded me of how cleverly Gold had maneuvered the body of Polonius in the Hamlet he directed with Oscar Isaac at the Public Theater in 2017. A more sinister aspect of Lazar’s comic King that I hadn’t noticed last time was his leering attitude toward the in-this-cast female Banquo, played by Amber Grey. It made me think that this staging entertained the idea of a different, and more immediate, way to make the children of Banquo kings. That sexual narrative remained implicit only, mainly through Lazar’s king being handsy and crude, but it suggested another way in which the Macbeth narrative, driven by the urge toward sudden violence, contrasted with the larger worlds of erotic and political possibilities suggested by Duncan and Malcolm, perhaps also by Banquo and the Macduffs, and above all, in this production, the witches.

The other major comic figure in the production was the brilliant Michael Patrick Thornton, who played Lennox, one of the Murderers, and also performed an oddly compelling stand-up routine at the start of the play, in order to make sure the Broadway audience knew about the superstitions about naming the Scottish play and also about King James’s witch obsession. Thinking about it now, beyond Thornton’s easy charisma and generous stage presence – I want to see him play all the parts! — I’m struck that, like the post-action song and soup ensemble, his opening monologue provided the other half of the pair of comic jaws inside which Gold placed Shakespeare’s tragedy.

Is that emphasis on meta-comedy enclosing the tragic core the “right” way to play Macbeth? Beats me. It’s not the usual way. My basic position is that all Shakespeare’s tragedies contain comic threads, as all the comedies have tragic movements, and the romances and histories walk across sides of the street. I love the idea of building and celebrating a comic superstructure that surround the uber-violent ambition of the central couple in Macbeth. I wonder a bit about whether someone who doesn’t know the play well, or who is seeing it for the first time, would react to Gold’s semi-arcane machinations. But I enjoyed trying to puzzle it out!

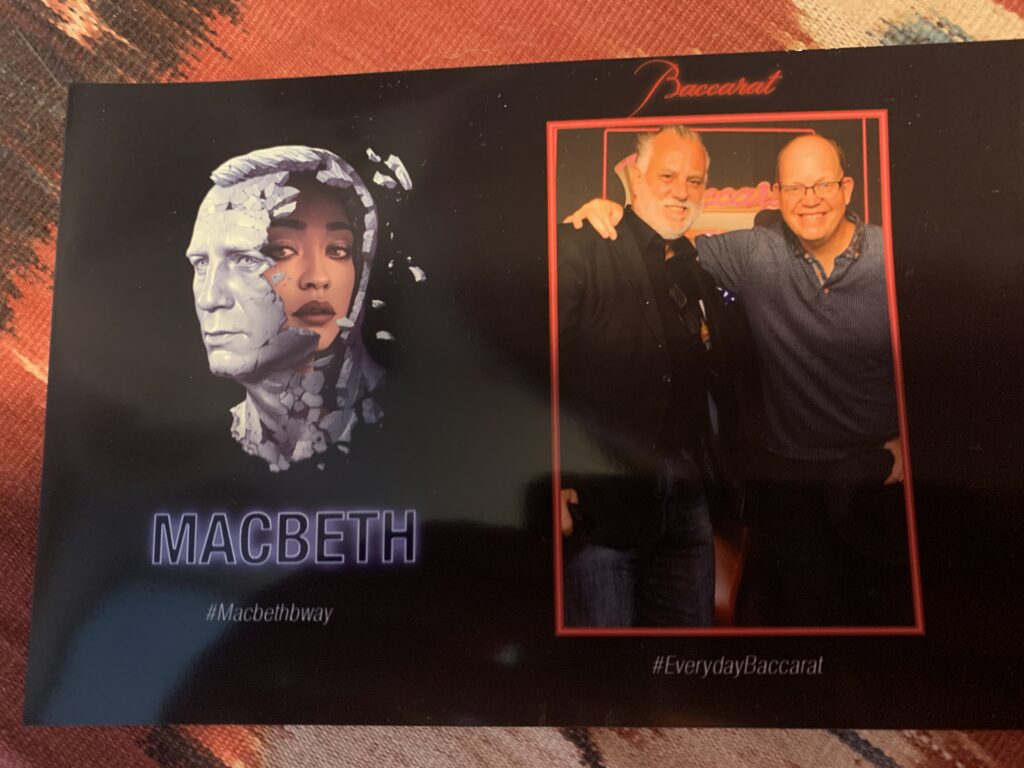

The main reason to get to the Longacre between now and the end of the play’s run in early July is Ruth Negga’s incandescence, especially in her solo scenes, when she unsexes herself in act 1 and sleepwalks in act 5. I also thought Daniel Craig’s performance had mellowed slightly from the preview I saw in April – he leaned into the intimacy that we who have spent years with his James Bond feel. Even in his moments of rage – “Full of scorpions is my mind, dear wife,” he shouted red-faced at his Lady in act 3 — Craig connected to the crowd, sometimes through a comic aside or gesture. At the end of the performance he slumped against the stage wall, visibly exhausted, happy, surrounded by his community.

Building that kind of community in the face of a violent world is not a bad way to think about what live theater does. I’m not sure this Macbeth is perfect, but I’m glad to have seen it twice.