What is theater if it’s not a con, a gull, a way of looking at things and people and seeing something other than what they are?

What is theater if it’s not a con, a gull, a way of looking at things and people and seeing something other than what they are?

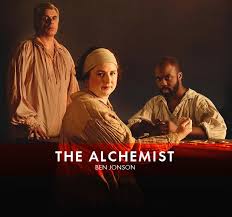

The Alchemist was Olivia’s and my favorite of this year’s Stratford plays. With a large, uniformly excellent cast headlined by Ken Nwosu as Face, Mark Lockyer at Subtle, and Siobhan McSweeny as Doll — the trio of reprobates who play while Master Lovewit is away — it’s the purest fun we’ve seen on stage so far. Olivia was especially taken by Joshua McCord’s Dapper, the lawyer’s clerk who at one point in the second half of the play was forgotten in a back room of the house until he chewed through his gag to remind Face that he was supposed to have an interview with the Faerie Queene. Doll’s cynical and magical turn did not disappoint. My favorite was probably Ian Bedford’s Sir Epicure Mammon, whose visions of global plenty — dolphin’s milk, rivers of gold, silver only for giving to beggars — distracted him even from his assignation with Doll. The half-dozen or so subplots crossed and converged in the fast-paced second act, with the return of formerly absent Lovewit eventually leading Face to resume his servant’s name, Jeremy, while Doll and Subtle hot-footed it over the back gate.

Face wasn’t quite done with us — he introduced the epilogue by flashing some RSC tickets, and counting up the total take in the house was that night. “Thirty-five quid each for the ground level,” he grinned. It came to quite a sum, though he didn’t reveal the full accounting, and he didn’t push the point too hard. We the audience were happy gulls, perhaps open-eyed gulls — but each time the curtain rises the money flows only one way, out of our wallets. It didn’t really darken a joyful production, but it left us thinking.

What is theater if it’s not a dream of power, a vision of unearthly beauty, a gamble that might be worth its price?

Maria Aberg’s direction of Faustus was the most conceptually ambitious of the four Stratford plays. Part dance, part fantasia, and occasionally a penetrating dive into ambition as an impossible dream, the play began with two actors facing each other, striking matches, and waiting to see whose will go out first. As I understand it, based partly on the wisdom of the pub, whoever’s match burns down first plays Faustus, and the other Mephistophilis. I don’t know if the actors can tip the scales or take turns somehow. We saw Sandry Grierson as Faustus and Oliver Ryan as Mephistophilis, though I kept imagining what it would have been like the other way round. Striking moments included the pageant of Seven Deadly Sins and, perhaps most of all, Faustus’s slow painting of the magical star-in-circle design onto the center of the stage floor, his labors standing in for the conversion of the scholarly books he tossed aside at the play’s opening into necromantic visions of power.

The other shocking bit was the appearance of perhaps 12-year old Jade Croot as Helen of Troy, the final gift Faustus asks Mephistophilis to bring him. (UPDATE: I’ve been assured she is at least 16, as required by UK child labor laws, since she performs every night.) Croot is a young theatrical pro, with stage productions of Oliver, Grease, Les Mis, and TV’s Doctor Who to her credit already — but the staging n of a young girl as the greatest temptress in literary history was hard to watch, especially since I was sitting next to my own 13-year old daughter in the theater! The Helen-Faustus pas de deux was very carefully staged: she had lots of agency and stage power, and the dance ended up not eroticizing their relationship, and perhaps emphasizing that Faustus could not access anything like real love. At the end I wasn’t quite sure why Helen was a child, despite the power of the scene.

I did think that this Faustus, like last night’s Hamlet, was a play about deep & unquenchable loneliness. No one could touch either the Danish Prince or the German magus onstage. What did Faustus really want from Mephistophilis, as his hour neared and he grew more and more frantic? Human connection was the thing he could not even name, from the start of the play when he rejected all forms of non-magical learning to the drama’s end when his demon-servant came to claim Lucifer’s reward. Non-human Mephistophilis was all that remained to the doomed Doctor, and the kiss that fallen angel gave to the dying man came just after midnight, too late, too inhuman. That perhaps unfelt kiss made a powerful ending to the play, partly because the chance for real emotional fulfillment seems to have been just missed.

Heading for London today, where Shrew and Macbeth wait at the Globe!

Leave a Reply