I drafted a review-response to this movie Saturday morning, after driving home late Friday night with surf tunes and sand visions gritting up my imagination. Before I could post it over the weekend, my site got hacked, & it took all day Sunday for my Thoreauvian web-maestro to get me back on line. As all Pynchonistas know, there’s no such thing as coincidence.

I drafted a review-response to this movie Saturday morning, after driving home late Friday night with surf tunes and sand visions gritting up my imagination. Before I could post it over the weekend, my site got hacked, & it took all day Sunday for my Thoreauvian web-maestro to get me back on line. As all Pynchonistas know, there’s no such thing as coincidence.

Oh, that was no found crab, Ace, no random octopus or girl, uh-uh. Structure and detail come later, but the conniving around him now he feels instantly, in his heart. (Gravity’s Rainbow 188)

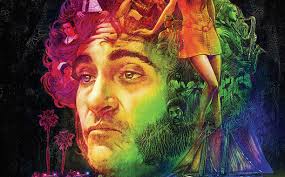

I spent the noontime hour Friday sneaking across town to catch Paul Thomas Anderson’s joyous & brilliant film of Thomas Pynchon’s last-novel-but-one, Inherent Vice, an homage to the stoner sixties via hard-boiled detective novels and a generous helping of conspiracy. The film opens and almost-closes with a narrow view of Pacific surf down a side-street, the view from the hippie bungalow where private eye Doc Sportello hangs his many hats, cleans beach tar off his feet, and occasionally faux-Afros his hair. The repeated view of the beach, one of the few repetitions in a busy and sometimes disorienting narrative, captures the film and novel’s imagined Gordita Beach, a loosely adapted version of the Manhattan Beach neighborhood where Pynchon lived in the 60s. It’s Utopia, and it keeps Doc happy with its surfers, seers, dope, travelers, and — since it’s the spring of 1970 in the film, and the long decline out of the sacred decade has just started — rich helpings of nostalgia.

The surf, only now and then visible, was hammering at his spirit, knocking things loose, some to fall into the dark and be lost forever, some to edge into the fitful light of his attention whether he wanted to see them or not. (Inherent Vice 314)

I have trouble writing critically about this film, especially now that the holiday cyber-nappers virus’d away the first draft of this post. (I kept a hard copy. Proverbs for Paranoids #6.) I loved watching it so much. I’m sure many old Pynchon hands will enjoy it too — the mid-day show at Lincoln Center was filled with grey hair, or little of it, as in my case — though I wonder a little about how friendly it might be to non-initiates. If you’ve not read the novel, you might want to start with this trailer first.

I can’t resist mentioning what we all knew going into the movie theater: the movie can’t dive all the way into the wild exhuberance of Pynchon’s imagination, any more than it can replicate his just-past-the-edge-of-control beautiful sentences. But it comes closer that I really dared to hope. It helps that Inherent Vice is Pynchon’s most linear novel, which isn’t to say it’s very linear, even in Anderson’s stripped-down version. The trimming was smart, though I missed some potentially distracting riffs: the road trip to Vegas that clarifies the real estate plot, and (as Anthony Lane also notes) the surf-saint with his piece of the True Board.

But the genius of the movie was that it got so much in, despite having to leave other things out. Joaquin Phoenix’s Doc played a perfect combo of confusion, generosity, and “paranoid skills” (318). Josh Bronlin’s Detective Bigfoot Bjornson was if anything better, eating up the screen with intensity, rage, and — particularly in a denouement that Anderson added to Pynchon’s ending-less novel — a sympathy for Doc to which he would never cop. Perhaps Anderson’s shrewdest narrative gambit was making Sortilege, Doc’s ex-receptionist turned full-time surf prophetess whose name refers to a Roman practice of divination, into a voice-over narrater who helped the film smuggle in lots of Tommy P’s prose:

…before she turned away, he could swear he saw light falling on her face, the orange light just after sunset that catches a face turned to the west, watching the ocean for someone to come in on the last wave of the day, to shore and safety. (Inherent Vice 5)

Anderson’s film does a good job jump-cutting Doc’s mostly-stoned “operational paranoia” into a fast-paced cinematic style. He briefly kicks into a higher gear during the action-movie semi-climax, when Doc, drugged on PCP by an Aryan Brotherhood baddie, fights a confusing three-way shoot out with Puck Beaverton the skinhead, Detective Bigfoot, and hit-man Adrian Prussia, who appears, in a partly-opaque backstory, to have killed Bigfoot’s partners some years ago. It’s a good scene, but I’m not sure that it’s the heart of the matter.

Some of my favorite bit-pieces in the novel, St. Flip of Lawndale who surfs a sacred & perhaps imaginary offshore break, Sortilege’s visions of the drowned Pacific continent of Lemuria, and especially the fog-frozen final tableau on the San Diego Freedway, couldn’t fit into Anderson’s crowded vision. That seems a pretty reasonable choice: he stuck instead with characters. He got great performances from Owen Wilson as semi-zombie surf sax player Coy Harlington, Martin Short as mad dentist Rudy Blatenoyd, Benecio del Toro as Doc’s (maritime) lawyer Sauncho Smilax, Reese Witherspoon as Assistant DA and Doc’s sometime girlfriend Penny Kimball, and many others. I missed the Lemurian riffs, but my favorite snatch of sentimental poetry from the novel got prominent voice-over treatment as Doc and Sauncho gazed out into the LA harbor:

…yet there is no avoiding time, the sea of time, the sea of memory and forgetfulness, the years of promise, gone and unrecoverable, of the land almost allowed to claim its better destiny, only to have that claim jumped by evildoers known all to well, and taken instead and held hostage to the future we must live in now forever. May we trust that this blessed ship is bound for some better shore, some undrowned Lemuria, risen and redeemed, where the American fate, mercifully, failed to transpire… (Inherent Vice 341)

(I wrote about that passage, plus Lemuria and the foggy ending, along with Bob Dylan, Shakespeare, James Cameron, in a recent essay in Jeffrey Cohen’s collection, Inhuman Nature. Read it all here, and support Punctum Books while you’re at it!)

But the true thing about this film, and this novel, is that more than any other one of Pynchon’s eight, it plays up the love story. You can feel the emotion in the opening sentences:

She came along the alley and up the back steps the way she always used to. Doc hadn’t seen her for over a year. Nobody had. Back then it was always sandals, bottom half of a flower-print bikini, faded Country Joe & the Fish T-shirt. Tonight she was all in flatland gear, hair a lot shorter than he remembered, looking just like she swore she’d never look. (Inherent Vice 1)

Shasta Fay Hepworth, Doc’s ex-old lady and from these opening sentences a hazy allegory of paradise lost, passes between both sides of the historical fence in film and novel, from Doc to real estate mogul Micky Wolfmann and (perhaps) back. Anderson sprinkles his film with flashbacks to the flower-bikini era, including a lovely sequence of Doc and Shasta dancing in the rain to Neil Young. Pynchon’s novel keeps that 60s Shasta just out of sight. She’s on Micky’s side when she comes to Doc’s place looking for help, entangled along with everyone else, even Doc, in rising tides of greed, ambition, and willingness to abandon the past.

Hollywood likes its women gorgeous and vulnerable, and to me Katherine Waterson’s Shasta — the Muse of the film — was the only actor who didn’t quite ace it. Pynchon’s heroines, from Oedipa Mass in The Crying of Lot 49 (1966) to New York-based PI Maxine Tarlow in Bleeding Edge (2013), aren’t immune to the charms of Bad Men like Micky, but they don’t feel quite as doe-eyed as Waterson’s Shasta, especially in the opening scene. Anderson is reasonably faithful to the novel’s strange reunion sex scene, which the irreplaceable maniacs over at the Pynchon wiki have calculated takes places during an extra non-calendared day between May 4 and May 5, 1970, within the otherwise-precisely datable narrative of Inherent Vice, which incidentally ends on Thomas Pynchon’s 33rd birthday. Doc and Shasta’s sexual reunion occupies that gap outside time, — and the implication, once we unravel the chronology, is that such a reunion is only possible outside of the fast-falling arc of history. Anderson doesn’t quite show it that way.

The film’s version of the scene is powerful and shocking, with a bit of erotic role-playing making the middle part of the encounter ambivalent, and Shasta’s “This doesn’t mean we’re back together” (307) making sure we don’t miss the point. The film is too knowing, and too committed to Pynchon’s tragic view of American history as a narrative of the Fall, to give much more than that.

What if it was a deliberate insurance hustle? Maybe Shasta could still get ashore in time, onto some island where maybe even now she’d be pulling small perfect fish out of the lagoon and cooking them with mangoes and hot peppers and shredded coconut. Maybe she was sleeping out on the beach and looking at stars nobody here under the smoglit L.A. sky even knew existed. (Inherent Vice 120)

Except that, in the movie’s end, it can’t resist giving just a bit more. After stopping back through the opening shot of the surf down Doc’s alley — at which point I was hoping that would be the last shot, thumbing its nose at narrative closure, what we want is the surf, man — Anderson added two short scenes about the two key relationships. Bigfoot bigfoots his way into Doc’s place by stomping through the glass door. They share a joint, the munchies, and — almost! — recognition. Then bright light shines down on Doc and Shasta snuggled together, him looking up behind dark shades and her looking slightly away and down. Together, more or less.

It’s hard to avoid closing with the love story, and Anderson probably resists it as much as he could. Though maybe I’m being over-picky: if there’s one thing the post-Gravity’s Rainbow run of “new” Pynchon novels, especially the most recent two, Inherent Vice and Bleeding Edge, has shown, it’s that the greatest American postmodern novelist has a soft heart. After crowing in Gravity’s Rainbow that “There’s nothing so loathsome as a sentimental surrealist,” (696), Pynchon since the 90s has seemed determined to embrace this self-caricature. Maybe Anderson’s semi-happy ending is almost true to that spirit? (Pynchon’s novels tend not to end in romantic clinches, but there’s plenty of sentiment among friends in Mason & Dixon and towards growing children in Bleeding Edge.) My sense is that Pynchon’s novels are less committed to choice in love than our pop culture wants to believe — sex in Pynchon is as much overwhelming force as life-defining alliance — but in stripping away so much of the centrifugal debris from the novel, has Anderson found, at its core, a simple love story?

I’m wondering now whether that final shot is Anderson’s attempt to capture Pynchon’s skeptically-redoubled version of human sentiment inside tragic history. Can we see in Shasta’s not-looking-at-us eyes “some heavy combination of face ingredients …that [Doc] couldn’t read at all” (3)? Or maybe also evidence of her claim that she was “never the sweetest girl in the business” (312)? In Doc’s confusion can we read both love and anticipated loss, a kind of postlapserian sense of History and human weakness, “back to his old wised-up self, short on optimism, ready to be played for a patsy again. Normal” (303). It’s a lot to get into one shot, and I’m not sure Anderson gets it all in.

I’m looking forward to watching the movie again (and again) to try to figure it out.

For those not in New York or LA, it opens nationwide January 9!

Leave a Reply