“What did you like about the piece?” reverse-interviewed Liz LeCompte after the screening of her film Rumstick Road, which she and Ken Kobland back-formed out of archival audio and video footage from the celebrated 1977 stage production she co-wrote with Spalding Gray, in the Wooster Group‘s originary performance. “It’s kinda morbid, now.”

The play and the film build themselves around audio interviews of Gray’s family that discuss his mother’s suicide in 1967, when Gray was in his mid-twenties. The film shows images of Gray and three other members of the Wooster Group on stage in 1977, screened along with crackling audio feauturing the voices of Gray’s father, two grandmothers, and the doctor who treated his mother in the 60s. The combined effect is powerful and eerie. Gray’s probable suicide in 2004, as well as the subsequent artistic histories of the Woosters and Gray himself, create a disorienting multi-temporality, inside and outside of the 1960s, 1970s, and 2010s. As Ben Brantley wrote in the Times, there were ghosts on the screen.

“It was like a scientific inquiry,” LeCompte said in her post-screening discussion with Richard Maxwell of New York City Players. The film showed “Rumstick Road” to have been intensely fractured, with moments of almost unbearable power. Libby Howes, playing the part of “Woman” and perhaps thinking of Gray’s mother, dominated one long scene by bowing her body forward furiously for perhaps ten full minutes. In a display of physical abandon she flung her torso forward recklessly, repeatedly, with full extension and flowing hair, as the voices of the family discussed Gray’s mother’s depression, her Christian Science beliefs, her devotion to Mary Baker Eddy.

My favorite moment, perhaps, was the lone speech by Gray’s maternal grandmother, “Gramma Horton,” who quoted Mary Baker Eddy’s teachings on the absolute superiority of spirit to flesh. Gray’s preface to this recording revealed that Gramma Horton had not wanted him to share her words on stage.

The emotional charge of the show flows from its compulsive open-ness, Gray’s defiant exposure of Gramma Horton’s urge to keep something private, of his father’s New England reserve, of Gram Gray’s being “not in sympathy” with her daughter-in-law’s religious intensity.

Everything, on stage and now on film, gets laid bare.

My working theory about the Wooster Group’s more recent plays — I’m writing a piece on “Cry, Trojans,” for the International Shakespeare Conference this summer — is that they build alienating structures in order to overcome them, at least partly, with emotion. Theatrical pleasure operates on both sides of coherence, sympathy, and identification.

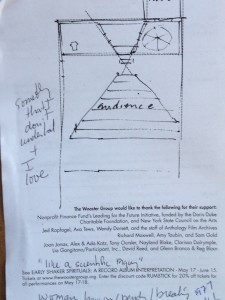

In the film’s final moment the eternally thirty-six year old celluloid ghost-Gray looks up at the audience and thanks them for coming. At that point the camera pans back, revealing in front of the stage the arrow-point of the fifty-person audience upstairs at the Performing Garage in 1977. A sketch by LeCompte in the program shows that the stage and audience together formed an X, the vertex of which was right in front of Gray’s face. Marking the spot.

LeCompte also said something about how she chooses work for the Wooster Group. “I try to find something that I don’t understand,” she said, “and something I love.”

Leave a Reply