The genius started with Virgilia. Virgilia!

She was lounging onstage before the start, as we all tried to figure out how it would work. The stage at the BAM opera house was deep, wide, and busy, full of modular furniture, couches, tables, and at least a dozen large TV monitors. The audience started out seated, looking up at a huge screen above the stage with a gnomic Dylan phrase on it. We also watched a digital crawl that provided translations from the Dutch and other useful facts — 297 minutes to the death of Cleopatra! — for anyone who could see it. Later, when we (the audience) took the stage we stood or sat or craned our necks looking at the action, or taking a break to order at the bars backstage right or left. I asked for a rum and tonic while Coriolanus was dismembered 20 feet away. The stage also contained make up tables for the actors on one side, and public email/twitter terminals on the other side. It got crowded, as the night wore on.

Virgilia started it, before I knew who she was. She sat on the couch as the play opened, staring up at the imposing face of Volumnia, praising her warlike son on the big screen. All the war scenes in Corioles were compressed into strobe lighting, so the first time we see the hero upon his return from the battlefield, he’s caught between mother and wife. His words give priority to his mighty mother over the wife he calls “my gracious silence,” but this performance punctuates Virgilia’s tears with lingering kisses. The deep physical pull between the lonely dragon and the upstaged wife — Virgilia cannot control her husband the way his mother can — activates the agon between sex and politics that finally explodes, almost five hours later, with Cleopatra. During the show I thought these two parts were played by the same actor, but now that I check the cast list, Janni Goslinga played Virgilia and Chris Nietvelt played Cleopatra. The two performances shared an explosive mix of eros and warplay that sits near the heart of director Ivo van Hove’s vision of politics.

Van Hove’s notes call the political vision of his production of these three Roman Tragedies “action in public,” and here the decision to open the stage to the audience — not really a new innovation, as the Village Voice notes — represents not just avant-garde dramatic play but an experiment in seeing what “free action” can mean in practice. Van Hove claims that Shakespeare “shows that politics is made by people.” His set designer and long-time collaborator Jan Versweyveld writes that the set for these plays “transforms the theater into a political conference.” Their show immersed all of us in political news, with the the digital crawl quoting headlines from Gaza and tweets from the audience, while a few of the on-stage monitors projected images of 21c century heroes during the show: Barack Obama during Coriolanus’s encounter with the people, Michael Phelps’s 200m freestyle triumph during the ascent of Julius Caesar, and John Edwards (!) when Antony heads back to Rome to marry his rival’s sister.

One of the best tweets on the #romantragedies thread, to which we were all encouraged to post tweets and pictures during the performance, noted, accurately, that the best part of van Hove’s high-concept theatrical flourishes was how well each one embodied the deeper metaphors of the plays. I read that sometime during the production and thought — exactly. That’s how the show worked I’ll try to explain a few of these moments.

Coriolanus’s melt-down press conference, in which he denounces the manipulative Tribunes in front of a TV audience, was a study in anger. “You speak as a punitive god,” protest the Tribunes, at which the general rages further. His denunciation of the corrupt “two-party system” drew applause from the high-minded Brooklyn crowd, but I kept recalling the opening kiss his mother had prevented him from enjoying with his wife after the battle at Corioles. The military hero raged against all distraction, against anything that moved away from his solitary warrior self — but on this stage there was no single center, only competing forces, mothers, wives, children, Tribunes and Senators and even the talking head of Barack Obama backstage. Plus lots of extras, including me.

The political world eats up this kind of solitude — this is what I take to be the meaning of the implied connection between Coriolanus and Obama, though our President seems to have managed the dissolution of his solitude better than the Roman general. Aufidius, who appeared twice on stage being interviewed by a Roman TV station, the second time when his armies were outside the gates of the city, was impassive and implacable, biding his time before consuming his ally-enemy at last. In a play about political failure and consumption, Virgilia’s almost-silent stage-plea for a more feeling world cannot stand before her mother in law’s dictum: “Anger’s my meat. I sup upon myself.”

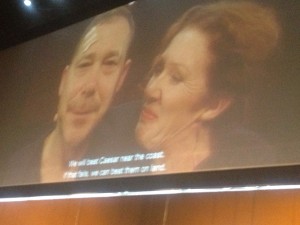

From the inchoate rage of Coriolanus the production moved seamlessly — no set change between the death of Coriolanus and start of Julius Caesar — to the high-stakes competition of Brutus, Cassius, and Caesar. Playing Cassius as a woman and then later playing Octavius Caesar as a woman in the final play suggested the slow integration of the Roman political world, from the violent masculine prehistory of Coriolanus’s Republic to the quasi-matriarchal empire of Octavius that follows the death of Cleopatra. The middle play, Julius Caesar, highlighted its female characters with a great stage coup, in which the tete-a-tete scenes of Caesar and Calpurnia and Brutus and Portia were played simultaneously across each other, such that each actor appeared to be answering both conversations at once. Calpurnia, played by Janni Goslinga, the actor whose Virgilia had failed to re-claim Coriolanus in the first play, was no more successful here in keeping her husband from being killed, but she and Portia provided a powerful template against which the Roman super-heroes measured themselves.

But the show-stopper in the middle play, perhaps predictably, was Mark Antony’s funeral oration. After a measured, polished, really quite beautiful speech by Roeland Fernhout’s Brutus — I was sitting about 5 feet behind him at center stage — Hans Kesting’s Antony swaggered to the podium, looked at the audience (I watched via video feed, since I was behind him), picked up his notes, and threw them away. Then he slouched around to the front of the podium, fell down, and sat still for almost two minutes.

We stared in near-silence at his stricken face, and I was thinking about media resources. In most plays, watching from seats, you can’t see close facial expressions unless you’re in the front row. But the video screens enabled this production to use the emotional resources of the close up as well as the shared emotional power that only crowded theaters can produce. Antony drew us to him by sitting exhausted and quiet, so that when he took up the microphone — “Friends, Romans…” (the words were in Dutch, of course, which meant I mostly couldn’t understand them, though a few old Germanic roots carried through) — we were all with him. And then he did with rage what Coriolanus hadn’t been able to do: he brought all of us all along with him.

I don’t think my description can do justice to the rippling force and mania of the speech: Antony ran through the theater screaming his lines (in Dutch), he carried the body of Caesar back on stage, he marked up a photo of the corpse with a red sharpie (which almost hit me when he discarded it behind him), he spat and dripped and cried. He waved around the paper with Caesar’s will. And we were all with him — because we were on stage, most of us, we were the plebeians. We were the ones who wanted the honorable Brutus to pay, the ones who, deep in our stomachs, felt that being reasonable makes a poor politics.

A six-hour production needs multiple high-lights, and Antony’s funeral oration wasn’t the only one. I’ll hit two from Antony and Cleopatra: the night before the battle of Actium, and the death of Enobarbus.

Before the battle, on Cleopatra’s birth-day, she and Antony perform “one other gaudy night” (3.13) as an elaborate kiss-and-dance that fulfills the erotic promise that Virgilia had offered some 270 minutes before with her husband Coriolanus. The “soldier’s kiss” and the reunion of the lovers — Antony has spent a fair amount of the play thus far making and breaking a political marriage with Octavia, Caesar’s sister — gestured toward a theatrics of personal connection, one that didn’t care much about world-shaping battles just a few hours away. As we looked at their happy faces explaining to a furious Enobarbus that they would fight by sea, not by land, no matter what “absolute soldiership” Antony had on land, it didn’t matter that they were throwing away the world. The soundtrack was lovely late Dylan: “It’s not dark yet, but it’s, gettin’ there…”

Even better, perhaps, was Enobarbus himself, played by Bart Siegers, who’d also been the inexorable Aufidius. Having betrayed Antony, returned to Caesar, and then had his treasure sent after him by his former master, Enobarbus runs mad. He also ran through the theater out onto Lafayette Ave. around 11:15 pm, howling and writhing his Dutch rage at the taxis and bike messengers. Again, it was both a great theatrical coup and a brilliant reading of the dramatic metaphor: the great Roman soldier, who knew to leave Antony because he knew Antony had ceased to be an effective leader, has found back in the Roman camp that the world of emotions and passion, of bodies and feelings, that he loved in Egypt has gone. So he ends up lying on cold pavement, with cars and pedestrians ignoring his madness, walking by him. So fares the feeling man in the cold Roman world. You taxis, you cyclists, you worse than senseless things!

I could go on about this show, talking about the brilliant bits of humor, as when Mark Antony almost forgets his new wife’s name, or the backstage hi-jinx, as when Octavia spilled a beer at the bar between scenes. But the full force of the production seems to me best captured by that image of Enobarbus on Lafayette Ave, crying out his pain to the uninterpreting streets. A brilliant metaphor for politics at an impasse.

If and when Toneelgroep does Shakespeare’s Histories, 8 plays in 12+ hours, I’m buying a ticket to Amsterdam.

[…] –A Production that Actually Made Me Miss New York (or Maybe Amsterdam) […]