Sometimes you get lucky and see a major theatrical star play a canonical role in a transformative way. The contours of the role remain familiar, but the actor inhabits them more fiercely than you expect. He surprises you, even though you’ve seen the play lots of times and don’t expect to be surprised. He fixes your attention whenever he’s onstage. At times he slightly distorts the way you see the play, bending it just a bit in his direction. You start to imagine a slightly different play, tilting slowly out of its usual orbit into a different perspective.

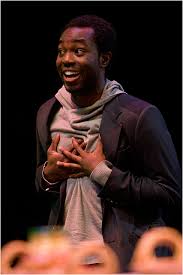

I drove home from Brooklyn last night with my imagination inflamed by Paapa Essiedu’s brilliant performance of Edmund, the Bastard of Gloucester and sub-plot’s villain in King Lear.

It’s true that I was supposed to be afire with a different performance. Anthony Sher’s mad King was strong and lucid. As he devolved from inacessible tyrant carried in atop a litter in the opening scene to doting Dad who doesn’t mind prison as long as he can sing with Cordelia “like birds i’the cage,” he became somewhat more engaging — but he never captured my attention the way Essiedu’s Edmund did. Sher was stately, plump, a bit formal in his clarity. Essiedu was the thing itself.

Anthony Sher as Lear and Graham Turner as the Fool

I’ve got a pet theory about the relationship of the plot and subplot in the final scene. While Edmund’s minions are killing Cordelia off-stage, the action presents a long interlude in which disguised Edgar challenges and defeats his till-then-triumphant evil brother Edmund. The combat set-piece runs for 145 lines in the Arden 3 edition (lines 90-235), or 35% of the stage time before Lear enters howling with his daughter’s corpse. (Actually, since the silent stage combat takes some time, the Gloucester brothers subplot occupies more of the scene than that percentage indicates.) In an unstageable gambit that seems meaningful to me, I imagine a split-screen for those 145 lines, showing the audience that while we enjoy the chivalric episode of the battling brothers, Edmund’s murderers hang Cordelia. If only we didn’t like sword-play so much perhaps we’d pay attention in time to rescue her! “Great thing of us forgot!”

Paapa Essiedu as Edmund

The relationship between plot and subplot in King Lear is a bit strange. The play is the only major tragedy to have a substantial independent sub-plot — such plots are more common in comedies — and the two stories come from very different sources. The main narrative of the King and his daughters is a medieval tale from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s twelfth-century History of the Kings of Britain by way of Holinshed, the Mirror for Magistrates, and the anonymous play the True Chronicle History of King Leir. The sub-plot of rival brothers and their blinded father comes via Sir Philip Sidney’s New Arcadia, published around the same time as the Leir play in 1590, but Sidney’s source in turn was the classical prose romance The Aethiopian History of Heliodorus — a book that’s my personal pick for the greatest mostly unread text in Western literary history. The sinuous way in which Shakespeare’s King Lear entangles and disengages the medieval chronicle history and the Byzantine Greek romance comprises a thorough study in the legacies of these major genres and story-patterns in early modern English literary history.

Last night, I was on the side of Heliodorus, Sidney, Edmund, and Essiedu, even though I know the production wanted me to be with Geoffrey, the Mirror, Lear, and Sher. I’m probably susceptible because my first book on Elizabethan romance narrative had a Heliodoran heart. But Essiedu’s intensity carried me along. He’s a rising star, as I already guessed when I saw his Hamlet in Stratford in 2016. I thought his Edmund was even a tick better. He’s one to keep an eye on!

There were some other good performances in the RSC Lear, including David Troughten as an imposing Earl of Gloucester, Mimi Ndiweni as a compelling Cordelia, and Nia Gwynne as a charismatic and beautiful Goneril, whose face-off with her father while he cursed her “organs of increase” was especially powerful. The understudy Patrick Elue did a great job playing Kent last night, and the appreciative cast gave him his own curtain call at the long play’s end. It took me a little while to warm to Oliver Johnstone’s Edgar, who was strongest when naked and mad, perhaps a bit less compelling when sane and compassionate.

There’s still time to get to the Harvey Theater to see this one before April 29!

Anthony Sher as Lear with Mimi Ndiweni as Cordelia