Being in prison means the loss of many precious things, but Pericles encourages us to believe that all losses are not final… — Taconic Correctional Facility in Westchester

Along with students, colleagues, and friends, I braved the pre-Thanksgiving press and the crowds protesting Mike Brown’s killing last night to see Rob Melrose’s fast, brilliant, emotionally powerful production of Pericles at the Public Theater. Inside of two hours we had it all: riddles, incest, shipwrecks (two!), starvation, cannibalism, pirates, brothels, music, magic. The actors played multiple parts and navigated exotic geographies, transitioning from Antioch to Tarsus to Pentapolis to Ephesus to Mytilene with the spin of a table. The traveling show had just completed a tour of the five boroughs with a minimal set: a table, a book, a pillow, a few three-legged stools (useful in the jousting scene), eight actors. Out of these things grew an emotional urgency and force that stayed with me as I waited on my way home, watching a “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” protest march surge around my stationary car on E. 14th Street, wishing I had spoken to my students as clearly about this week’s injustice as Karl Steel did to his.

By the end of the night I was right there with Pericles, needing help to feel what I was feeling. How can a story I’ve read and taught dozens of times still choke me up?

Give me a gash, put me to present pain,

Lest this great sea of joys rushing upon me

O’erbear the shores of my mortality.

The play opened with Flor de Liz Perez, who would go on to play Marina in the second half, singing Gower’s opening lines. The song was a great way to enliven the four-beat couplets that pound out the play’s narrative interludes. The show’s a-cappella music was one of the particular joys of the evening; actors not currently onstage provided beats, and several scenes, in particular the jousting and dancing at Pentapolis, were wonderfully festive. Often many voices collaborated on Gower’s long speeches, adding speed and variety to the dizzying geographical movement of the play.

The double casting choices were intriguing. I’ve often seen Marina cross-cast with Antiochus’s daughter, so that the virtuous savior of the play’s second half trumps the incestuous temptress of the first scene. Melrose’s cast, by contrast, cast the charismatic Tiffany Rachelle Stewart as Antiochus’s daughter and as Thaisa, eager suitor to Pericles at her father’s court in Pentapolis. Bringing these two parts together allowed Stewart to play two different visions of female sexuality: enticing and dangerous as the incestuous daughter, forthright but still powerful as Thaisa. The lingering echo of Antiochus’s daughter clung faintly to rediscovered Thaisa in the play’s final scene in Ephesus, so that her play-closing lines to husband and daughter — she calls them “mine” and “mine own” — reunite the family while also granting dramatic power to the sexuality she has presented in multiple guises.

Instead of cross-casting Marina with the evil daughter, the play’s second-half heroine matched up with ancient Gower, the medieval poet-ghost who narrates the complex comings and goings of the play in the eastern Mediterranean. I love this choice, which renovates the ghostly narrator and also gently reminds us that it’s the young girl, not any of the kings, queens, or priests in the play, who controls the plot after its mid-way break. Marina confronts a murderer, pirates, customers and overseers of a brothel, a sexually eager governor, and finally her own melancholic and silent father. “Virginal fencing” is the phrase that lord Lysimachus, played with stately grace by Christopher Kelly, uses to describe her dialogue, and I was struck last night by the connection between her rhetorical combat and the chivalric jousting and dancing at which her father excelled earlier in the play. Marina is one of my favorite figures in Shakespeare because of her oceanic connections — I’ve called her Shakespeare’s Aquawoman — but in thinking about her crossed with Gower last night, it seemed to me that more could be said about how she bears the power of a literary tradition — the virtuous saint who cannot be corrupted — and also about how her varied and strategic rhetorical modes structure the second half of the play.

There were some other interesting cross-casting choices, including David Ryan Smith as Antiochus and Simonides, and also great comic work by Ben Mehl as the criminal trio of Boult, Leonine, and Thalliard. Raffi Barsoumian’s Pericles was wonderfully naive in the early scenes, and I was pleased to see him, after he has married Thaisa and reasserted his aristocratic idenity, find the fishermen who rescued him to give them their due reward.

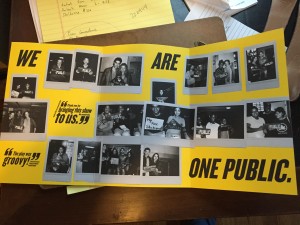

Redemptive theater makes a nice pre-holiday treat, though the contrast with bitter realities was stark when I encountered the protest march after the show. The juxtaposition between Shakespeare and 21c politics reminds me that the Mobile Shakespeare Unit represents the furthest out-reaching effort of the Public Theater’s democratic vision, taking free Shakespeare to prisons and mental institutions and the outmost fringes of boroughs that don’t always feed at Manhattan’s cultural buffet. The poster from last night’s program shows pictures of the cast and audience members during the Mobile part of the run. “We are One Public,” proclaims the headline, and the page is filled with smiling faces and testimonials from places like the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility and the Park Ave Armory Women’s Mental Health Shelter. Whenever I’m tempted to think that Shakespeare is too canonical, or too white-male, or too whatever, I’m reminded by outreach like this of the positive value of literary culture. One thing we as teachers and Shakespeareans like to show show is how our rage for justice and love and redemption share space inside a cultural heritage that is also, then and now, encrusted with violence and injustice. (Rick Godden and David Perry have written eloquently about this subject today.) There is plenty of violence legible in that inheritance — last night the comic bluster of Marina’s near-rape had me thinking uncomfortably about the recent news from college campuses — but Shakespeare and literary culture remain places to teach awareness and to imagine responses. I was struck last night by the joy and awareness of this production.

I’d feel sentimental if I said this in my professorial persona, so I’ll let another New Yorker who saw this great Mobile Pericles this month have the last word:

You brought light to a dark place. — Riker’s Island Women’s Facility

Leave a Reply