I was feeling a bit nervous about this one.

I was feeling a bit nervous about this one.

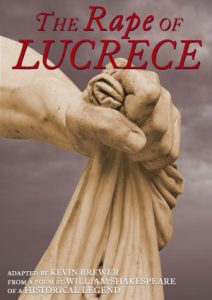

Every semester I bring my undergrad Shakespeare classes to live productions so that they can see how Shakespeare speaks to contemporary concerns. But this new play, based on Shakespeare’s narrative poem, “The Rape of Lucrece” (1594), seemed just a bit too on the nose in October 2016. The New York Shakespeare Exchange has been working for over eighteen months on the production, but they could not have guessed that its opening week would see repeated claims of sexual assault dominating the final turns of a Presidential election campaign. Sex, politics, assault, male domination: maybe a bit much, even for a class on Shakespeare and Political Rhetoric?

I was worried, at this painful and unsettled moment in American politics, about bringing a class of college English majors, mostly women, to a play about politicized sexual assault. In the end I trusted the collective wisdom of theater: the actors, the playwright, Shakespeare’s language, this ancient Roman story, the audience. I also trusted my amazing students, who both in class and at The Clemente on the Lower East Side last Thursday night, faced up to the long and living history of political misogyny that the story both represents and responds to.

The evening started about ninety minutes before curtain with a pre-show conversation between a half-dozen brave students and a trio from the company: Cristina Lundy, the director; Jessica Cauttero, the dramaturg; and Kevin Brewer, the playwright. The students volunteered their thoughts about the poem’s oblique and painful nature, the insufficiency of the rapist’s banishment as punishment, and the imaginative consequences of following Tarquin into Lucrece’s bedchamber. I didn’t know it at the time, but the conversation helped set up the split that NYSX emphasized in their rendition of Shakespeare’s narrative. We talked about the politics of ancient Rome, and the way the eternal city’s mythic history builds itself atop stories of sexual violation: the mysterious pregnancy that leads to the birth of Romulus and Remus, which Jessica suggested may have been a way of concealing a rape story; the rape of the Sabine women; the story of Lucrece. As in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the story that must be repeated, survived, and out-lived, begins with male sexual aggression.

We talked about Trump. How could we not? Cristina noted the play would feature armed camp talk, the Roman equivalent of locker room talk. We also talked about the Mockingjay, and the dehumanizing consequences, for Lucrece in Roman history and Katniss in the third book of the Hunger Games trilogy, of having a woman’s wounded body become a political symbol.

I’m thinking about that question now, in the wake of Michelle Obama’s deeply moving speech in New Hampshire. Might that brilliant speech have discovered a new language to respond to the ancient and brutal story of powerful men and victimized women? Might the examples of so many women coming forward over the past week to tell once-hidden stories suggest that Lucrece’s ancient example of shame and self-harm is no longer the most powerful response to these crimes? I hope so.

In addition to its implicit commentary on national politics, this play of “Lucrece” also managed to include almost everything we’ve discussed in the first two months of the semester. A new character added to the play was the young Caius Martius, who when he grows up will become the Roman hero Coriolanus, in a play our class finished last week. The production also added material about Lucius Junius Brutus, a friend of Lucrece’s husband Collatine who would use the occasion of Lucrece’s rape to banish the Tarquin family and, according to legend, found the Roman Republic. In a gambit that my students recognized from Hamlet, this Brutus pretended during the first half of the play to be a drunken fool, only to spring the trap and lead the forces assembled against Tarquin at the play’s end.

Aaliyah Habeeb’s Lucrece and Leighton Samuels’s Tarquin occupied the play’s center with charisma and aplomb. They were particularly strong in a long added-in section in which Lucrece showed the visiting Tarquin a set of statues from Greek epic. When she answered Northrop Frye’s which-Homer-are-you question by telling Tarquin that she loves the Iliad more than the Odyssey, I admired the deftness of playwright Kevin Brewer’s construction: Lucrece’s high-minded aspiration to tragic epic would preclude any subtle strategies for survival like the slight of hand with which Odysseus’s wife Penelope kept her suitors at bay, unweaving by night what she wove by day.

But among a series of excellent performances, including the versatile Brandon Garegnani as Brutus and Shawn Williams as Collatinus, the stand-out for me was Gabby Beans as Mirabelle, Lucrece’s servant and another addition to the story. Moving back and forth between the army’s camp at Ardea and Lucrece’s house at Rome, she served as an emotional register, suspecting Tarquin before anyone else, concerned about Lucrece, aware that after the assault, when Lucrece’s male allies including her father and husband, start talking politics they are likely to forget about her.

The private-v-public split, which oscillated between considering Lucrece as an individual and treating her rape as a political symbol, became particularly stark in the final sections of the play. Lucrece’s suicide came when Mirabelle was briefly offstage and Lucrece’s male allies were distracted by political strategy. Once Lucrece has become the symbol of their Republic — their Mockingjay — she ceased to be present for them as a person. It was shocking to watch her stab herself while half the stage was filled up by men who love her not watching.

I don’t want to give away the surprise addition to the story in a scene that appears neither in Shakespeare nor Livy — go see the play before Oct 22 to learn what happens at the end! — except to note that it extends the divergence between Lucrece as symbol, who enables Brutus and his allies to expel Tarquin and found the Republic, and Lucrece as woman, whose cruel fate must be mourned and also requited.

On our way out, one of my male students, told me, “This was much better than Shakespeare’s version.” It makes me happy to think that, even as current events show us that male sexual assault still brutally punctuates our political debates, young men and women are recognizing that these cruel old stories need better and more just endings.

Leave a Reply