A bunch of academics talking in a windowless underground room don’t amount to anyone’s idea of a revolution. But as we Nashers gnashed at the Folger’s weekend symposium on the works and contexts of the Elizabethan writer Thomas Nashe, I kept thinking about sudden, violent, unexpected change. Maybe it was the hurricane roaring through Cuba on its way to Florida. Maybe it was Nashe’s incandescent, maddening, dizzying prose style. Maybe my own years-ago joke-and-fantasy that The Age of Thomas Nashe might displace those other proper names we assign to the late sixteenth century (Elizabeth, some guy named Will). Something was in the air this past weekend.

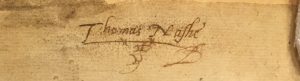

The #NasheBash represented a collaboration between the Folger and the Thomas Nashe Project, a mostly UK-based effort spear-headed by Jennifer Richards, Andrew Hadfield, Cathy Shrank, and (in Amherst, MA) Joe Black. It was a treat to have the four lead editors and other members of the Nsshe tem in DC this past weekend, so that the particular challenges of editing Nashe — in addition to reading him, writing about him, and teaching his works — structured our conversation. Jenny and Andrew’s opening talk oscillated between a desire to materialize or oralize this figure — I’m still mulling Jenny’s fascinating thoughts about how to conceptualize and make tangible “Nashe’s voice” — and also to respond adequately to Nashe’s breathtaking range of reference and allusion. In some ways these are opposite projects: to write good notes for Nashe means building an intellectual superstructure to support and contain his wayward prose, but to attend to Nashe’s voice might include feeling lost at sea.

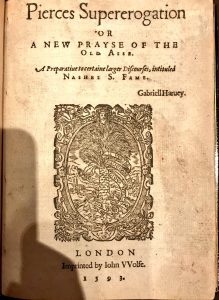

The two-voicedness of the opening talk that Jenny and Andrew gave us on Thursday night also set a great example of exchange and dialogue. We talked a lot this weekend about insults — Nashe was a brilliant writer of invective, and his pamphlet war with Gabriel Harvey generated some extraordinary invented works and bafflingly ornate sentences. All weekend I kept hearing Nashe in two voices — as in Kate De Rycker’s performance script for Terrors of the Night, which I sadly missed this past May at the Globe’s indoor theater — and sometimes those voices were Jenny’s and Andrew’s, though of course there were may others of us speaking, some thirty-odd in total.

I won’t try to re-cap the dozen short talks, each presented in groups of two, or David Scott Kasten’s eloquent closing remarks, including an intriguing turn to the “Englishing” ambitions of late sixteenth-century English authors. Instead I’ll reimagine the discussions through some keywords that percolated through our discussion. Apologies in advance for elements of our conversations that I won’t get to, not to mention failing to cite all the brilliant things said by so many people. I’m writing on the 6 am northbound Amtrak, bouncing through Maryland just now, and not every book of memory is perfectly clear.

Energy

Might energy — intensity, power, force — be a defining characteristic of Nashe’s prose? We gestured several times toward enargia as a classical rhetorical trope (though without citing Puttenham I don’t think), and many of us in different ways — Bob Hornback discussing Nashe’s debt to post-Tarlton extemporaneity in prose, Reid Barbour on a preacherly style, Joan Pong Linton on performance, Adam Zucker on pedantry as anti-model and, oddly, also ideal — responded to the coiled-spring quality of Nashe’s prose. Perhaps my favorite moments in the many talks, and the wonderfully capacious hour-plus of conversation that followed each pair of talks, happened when we let Nashe’s phrases and coinages and glorious insane sentences wash over us. It’s an old idea — C.S. Lewis’s idea, in fact — that Nashe is best understood as a “pure” stylist. I’d resist Lewis’s somewhat disembodied or abstract Nashe, but he’s not entirely wrong about style.

Referentiality

Poop jokes are the best jokes, and an early morning trip through Nashe’s scatological obsessiveness by way of Alan Stewart’s editing of the letter to William Cotton and its attacks on Gabriel Harvey showed everyone, with almost uncomfortable physicality, how deep into the shit Nashe dove. Alan’s notion, which Adam Zucker later suggested might plausibly represent a foundational claim in Nashe studies since McKerrow’s early 20c edition, that Nashe is somehow the heart or quintessence of “the Elizabethan” (or maybe the 1590s?) emerges from the breadth of reference in his short career. I learned about many new and utterly convincing Nashean intertexts, from patristic writings to London sermons, clown prose in print, almanacks, commonplace books, Aretino’s varied career (he’s not just a pornographer!) and even Apuleius’s Latin “Greek romance,” The Golden Ass. Nashe is a maze, a plurality, sometimes an editorial nightmare — the melancholy in Andrew’s voice describing the baffling nature of some sentences in Have With You to Saffron-Walden was palpable — but always a step or three ahead of conceptual pursuit.

Orality

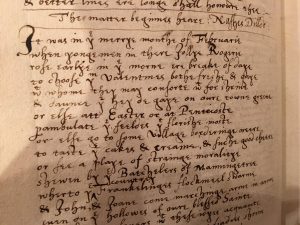

Jenny’s efforts to unpack the oral/aural nature of Nashe’s prose, and to connect his works to Elizabethan and later traditions of performance made a valuable through-line over the weekend. Joan Pong LInton and Adam explored Nashe’s connections to Elizabethan drama, Heidi Brayman guideed our attention to reading practices including oral reading, via a lovely manuscript compression of Greene’s Menaphon, in the paratextual margins of which Nashe first entered print. Andy Fleck’s survey of routes into Nashe, from EEBO to the old Penguin paperback edition to the in-progress OUP set and the Broadview teaching edition of The Unfortunate Travleler he’s currently editing also emphasized the variety of the ways into this career.

Velocity

I tried, in my talk on “Nashe’s geographies,” to build off Kristen Bennett’s great discussion of cosmological disorientation to get at Nashe’s peculiar charm.. I’m not sure I got all the way there, and at times over the weekend I worried just a little bit that our collective love for our guy Tom might slightly obscure his less attractive habits, including violent rhetorical excess and a studied misogyny that extends to quasi-feminine genres such as romance. But I do still like a formulation I uncovered early in my talk: Nahse chooses “velocity over identity.” That seems to me to start to account for both his attraction, for Nashers like us, and also his off-putting qualities, for readers from Gabriel Harvey to at least some of the students on whom we have foisted, and will continue to foist, our favorite Elizabethan proser.

Parody

Sam Fallon, one of many early-career scholars who I was delighted to meet this weekend, gave a smart talk on Nashe’s plural and unstable genre practices. He suggested that parody as a “characteristic mode” more than a generic kind might be a useful organizing principle. I very much agree, and I think the “para” in “parody” might be useful to think with in making sense of Nashe’s dense referentiality and also his violent energy. As with early texts such as the Anatomy of Absurdity and the prefaces to Sidney and Greene, Nashe performs a quasi-critical and partially parasitical engagement with 1590s literary culture. Maybe that’s why we lit crit types love him?

I especially value the sense in Sam’s talk of how parody, and other of our shared terms such as referentiality and even energy, flow from Nashe’s engaging with heterogeneity. I was struck by how many non-London landscapes got evoked in our conversation, from Great Yarmouth to the Isle of Wight to (in Kristen’s talk) the cosmological spheres. There’s an old tradition, that I suspect McKerrow’s early and bibliographically important edition helped motivate, of reading Nashe through terms such as “singularity” (as in Stephen Hilliard’s book) or “the scandal of authorship” (Jonathan Crewe’s term). There’s something to that reading, certainly,but I also like to think about Nashe in and through collectives — including the collective body of Nashe scholars, some of whom assembled in the Folger this weekend. “My people,” as quite a few people said over the course of the weekend.

Ephemerality and Extemporaneity

Jenny Anderson’s paper on the pamphlet as material format and discursive type dove-tailed wonderfully with Ian Moulton’s provocative talk on the “bad career move” of Nashe’s unremarked death and his failure to consolidate a laureate career like his sometime collaborator Ben Jonson. I think the ephemeral is a great term to think Nashe with, both because of its material connection to his printed output and also because the material fragility of the pamphlet echoes or resonates with his obsession with the extemporal. Bob’s quite stunning talk had already powerfully connected Nashe to extemporal post-Tarlton clowning in print, and also with Falstaff. I also think Nashe associates the “extemporal vein” with his sometime friend, mentor, and semi-rival, Robert Greene. I suspect more could be said about Nashe and Greene in the first few years of the 1590s: Greene’s prose romances had in the 1580s the popular success that Nashe never quite managed to achieve, but the final turns of Greene’s career before (and shortly after) his death in 1592 indicate a Nashean restlessness. Nashe’s genre experiments in the mid-90s respond to the genre-scatterplot of Greene’s his final turns to crime pamphlets, repentance tracts, and anti-Harvey invective – but given Greene’s penniless death, one wonders what Nashe thought he was following.

Partial Belonging

In trying to make sense of Nashe’s waywardness across several levels, including geographic ideas, generic variety, and syntactic complexity, I suggested the term “partial belonging” as a kind of analytical hedge: it signals Nashe’s double-facedness, his desire to be both “in” and “out,” plural and singular, knowing and unknowable. It’s also a term that for me speaks to the nature of early modern genre in theory and practice, which both operate as modes of categorization and appeal to hybrid contamination and the building of new kinds.

I’m left, after an “exhilarating” weekend (to repurpose one of David Scott Kasten’s closing descriptions of Nashe) thinking about the paradox of how a microscopic exploration of a single idiosyncratic figure can open up vistas. Alan’s notion that Nashe, if we could understand him (which we can’t), could explain all of Elizabethan culture points in one direction, and Ian’s provocative connections between Nashean invective and the vitriol of internet troll culture in another. I want to go both ways, and all the other ways too. Symposia such as this one are always about addition — I’ve come away with a long list of things I want to read, and projects I can’t wait to see emerge into print — and even more about engagement and entanglement. I’m not sure what I’ll next write about Nashe, but I’m so happy to see his works driving so many conversations.

Two last things, in a Nashean spirit of excess: first, one element of the joke of The Age of Thomas Nashe, which had its origins in a Shakespeare Association of America seminar co-run by Joan Pong Linton and Stephen Guy-Bray, was that we’d plan a hostile takeover and rebrand the SAA as the Nashe Association. Nashe might have chafed at being cooped up in the bottom floor of Shakespeare’s house, or even at sharing space at our wine-reception with a First Folio yesterday evening. But Nashe, who never found the patron he desperately wanted in his lifetime, was housed so well beneath the Folger’s capacious umbrella, under which premodern culture thrives and flourishes. We only talked a little Shakespeare this weekend, and didn’t really take up the question of how closely Moth in Love’s Labors Lost is meant to represent Nashe, but the old guy felt more beneficent than he sometimes can.

Lastly — the pleasures of the weekend were also made possible by all the other symposium participants whose names I’ve not mentioned and whose contributions came by way of after-talk discussion, not to mention hallway banter and around the bar extrapolation. There are some great projects-in-process that involve Nashe, and I look forward to seeing them move forward. It was a pleasure to meet new people and hear new voices.

After-lastly, in hasty postscript: thanks to the Folger itself, especially Kathleen, Owen, and Elyse. I didn’t have time to sneak into the Reading Room on this trip, but I’ll be back in DC in March or April. As always, I’m Amtrak-ing northward this morning with an eye on my next southbound train.

Happy travels to all Nashers and (to borrow one last phrase from our weekend) Nashe-adjacents!

[…] an enthusiast, and I enjoy all manner of academic events, from specialist conferences on Thomas Nashe to public round-tables for World Oceans Week. But it’s rare to be part of an event that draws […]