What if everyone was always bringing in a wall? All together all the time!

It’s one of the meta-dramatic paradoxes of Midsummer, which I’m not sure I’ve seen this joyfully performed since the glorious early-00s Donkey Show days of disco Shakespeare at El Flamenco in Chelsea. If the play calls for “wall” but you have just actors and no set, how do you stage the wall? The answer, as told in two-voices by the double-bodied male-and-female Snug the Joiner in Eric Tucker’s stunning production, is for actors to play wall — to entwine and tangle and make walls from human bodies, which turn out to be able to fashion themselves into almost anything.

Five actors with essentially blank black and white costumes played all the play’s parts, often — as in the opening moments — passing the roles around, so that everyone got to play some version of Duke Theseus and his buskin’d bride. I heard someone complaining at intermission that the action was hard to follow, but the house last night was mostly students, from St. John’s and Baruch College and I think some Manhattan junior high school. The kids liked it, or at least I think they did. I liked it too.

What I mean about always bringing in a wall is that the cast played almost entirely as a collective, all five using their bodies together to provide each other with everything from scenery to props. Some of the bits were easy to interpret, the flapping hands behind the backside that signaled Puck’s fairy wings, the undulating arms of the Faerie Queen, the clopping pointed hands that were Bottom’s ass hoofs. Others were gorgeously random — the Jeopardy theme and Girl from Ipanema hummed as transitions, Demetrius speaking maybe a third of his lines in Spanish, the slow and painful not-in-unison movements of Snug the Joiner, whose two bodies got my vote as best performance of the night, despite the hard work and brilliance of Jason O’Connell as Bottom and Puck, and many other roles besides. His Brando-as-Stanley Kowalski Pyramus pleased the crowd, but I’ll especially remember the coup de theatre that ended the play: he buzzed into being the mosquito through which he’d previously indicated the invisible presence of Puck, grabbed the bug between his fingers, squeezed, popped it into his mouth, snapped his fingers, and just like that – play’s done!

To always bring in a wall the five players lumped themselves into one mass, shoulder to shoulder or smushed in a pile or sprawled out across Titania’s bower. They made themselves into everything that was not there. All the actors handled the language well, but the heart of the performance was physical. I’ve seen a lot of productions that play up Shakespeare’s obscene puns on the wall’s “chink” by having the lovers kiss through another actor’s legs, but I’d never before seen actors double-activate the puns by thrusting first a female then a male crotch forward. When Thisbe lamented to her lover, “I kiss the wall’s hole, not your lips at all,” the multibodied wall fell on top of her and — well, I think you get the idea.

I wondered during intermission if they could possibly keep up the pace. Each new scene redoubled the physical jokes and tricks, and it’s hard to keep pulling off such things for a full 2 and 1/2 hours. The second half turned more overtly sexual, including a five-way tryst in Titania’s bower that I suspect embarrassed the junior high kids. The flash-cuts between the players and the aristocrats during the closing on-stage performance of “Pyramus and Thisbe” — all five actors played in both groups, so the shifts were communicated just by posture and changes in accent — were fun, but perhaps a bit more obvious than some earlier moves.

My favorite moment in the play, and one of my favorite speeches in Shakespeare, is Bottom’s description of his dream of loving the Faerie Queen. O’Connell didn’t botch it at all, but I’m not sure he got all the way to the heights. It’s a speech about error that teems with errors, a lyric vision in prose, and a hymn to the power of art spoken artlessly. Like so much of this play, it’s forgiving in performance but also very hard to strike dead on:

Methought I was, — and methought I had, — but man is but a patched fool, if he will offer to say what methought I had. The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen, man’s hand is not able to taste, his tongue to conceive, nor his heart to report, what my dream was. I will get Peter Quince to write a ballad of this dream: it shall be called Bottom’s Dream, because it hath no bottom. (4.1)

Maybe the slight lack I felt at this moment opened up because it’s a solo, and this production’s best bits required all five players playing. Bottom played all the parts, Egeus, Puck, and the Weaver too, but what he relied on wasn’t unobtainable faith but super-charged flesh — Titania’s shout for joy at loving an ass, Hippolyta’s rage, lovers running through human woods.

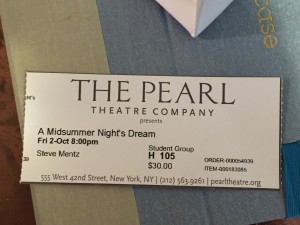

I wish I could go back tonight! Get to the Pearl before the run ends on Halloween!

Leave a Reply