A man’s body lies prone, face up with eyes closed. The image repeats itself, with different bodies, some living, some ghostly, some just playing dead. In the opening scene, a young man in black stares at the body of his father. By the last scene, we’re staring at the young man’s body.

The Public Theater’s current Hamlet features Star Wars: The Force Awakens leading man Oscar Isaac as the body everyone loves to watch, but it’s also notable for Sam Gold’s aggressive direction and some other great performances, especially Peter Friedman as Polonius and Ritchie Coster, double-cast as Claudius and the ghost of Old Hamlet — which meant the brother and his murderer were the same man. What Queen could leave “this fair mountain” to “batten on this moor” (3.4) expostulated Hamlet in the closet scene, holding up two pictures of the same face. No wonder Gertrude thought he’s mad!

Isaac’s was the face that brought me and my fourteen year-old daughter eagerly to a nearly four-hour show, and we both agree that he was worth every minute. I’ve not seen too many of the movie star Hamlets in recent circulation — no Cumberbatch, Fiennes, or Tennant for me — but it’s hard to imagine that any of them were as engaging, moving, or constantly entertaining as Isaac. From the intense gaze with which he stared at his father’s corpse in the opening through a wonderfully playful series of scenes in antic underwear — as many reviews have noted, this is a four-hour Hamlet that takes the comic undersong seriously — he simply dazzled. In a performance dedicated to his recently deceased mother, as movingly detailed in this Times article, Isaac surfaced an emotional availability and communicative force that captures the true “purpose of playing” (3.2). I know that as a card-carrying Shakespearean academic I’m not supposed to swoon for a Rebel Pilot, but he really was great. Olivia thought so too.

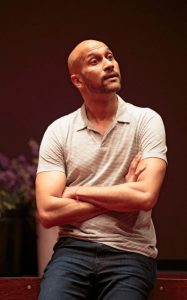

One of my favorite moments in Isaac’s performance was his intense delivery of the advice to the Players, in particular the admonition that the clowns not overplay their parts. He delivered those lines directly to the comedian Keegan-Michael Key, who was the Player King in the dumbshow and also an authoritative Horatio. As Player King, Key rejected Hamlet’s advice in a wonderfully excessive scenery chewing death. The dumbshow placed Key’s body in the “rest position” of the production, lying on his back, receiving poison in his ear, like a patient etherized on a table, as another poet says. In some ways the dumbshow, in which Key’s comic gyrations insisted that even the dead aren’t quite dead yet, seems to me the “heart’s core” (3.2) of this production: his body lay prone like the Ghost’s, Polonius’s, and eventually Hamlet’s, but his writhing antics showed motion under death’s silence.

There was lots more to like about Isaac’s Hamlet. He started the old chestnut of “To be or not to be” from rest position on the table, staring up at the ceiling, and in slow cadences engaging the overfamiliar lines. At this point we the audience wanted, and for a time could not have, his actorly attention: looking up and away from all three sides of the crowd, he played his death-seeking soliloquy as refusal to perform, to look at us, to play. For most of the performance he was a prince who loved playing and loved people, most of all Horatio but even — in some of my favorite exchanges of the performance — Polonius, whose old-man pseudo-wit projected the regal dignity that Coster’s violent Claudius eschewed. Was this the only Polonius I’ve seen that really showed, beneath his foolish pomposity and staleness of wit, the stature on which Claudius relies? “The head is not more native to the heart,” says the king about his advisor, perhaps aping Polonius’s own cadences, nor “The hand more instrumental to the mouth” (1.2).

Sometimes I think my increasing taste for Polonius might have to do with my having just entered my own 5th decade, at which point it seems pretty clear that I am not prince Hamlet nor was meant to be, though I still sometimes play insufferable Dad to a brilliant daughter. Polonius may be a poor father and indifferent wit, but he’s a lively genre-theorist and, at least in this production, a charismatic presence. Like many other reviewers, I was a bit perplexed by the scene in which he’s barking orders from the almost onstage toilet (2.1), but in general he was a highlight. He was much missed after his death in 3.4, which also marked the second interval. (Incidental & perhaps trivial aside: the between-intervals section of this production ran from “To be or not to be” [3.1] through the disposal of Polonius’s body [4.3] — is there a more relentless hour of theater in the language?) Even after being killed Polonius had one last comic turn, when antic Hamlet, seeking a place to stow the dead body, asked the audience member across the stairwell from me to move, propped Polonius up in her seat, put sunglasses on him and a Playbill in his hand. He sat there quietly, “most still, most secret, and most grave / Who in life was a foolish peating knave” (3.4).

A few scenes later, after his body was mock-buried by Ophelia with dirt she lugged in from planters in the lobby, Friedman started up from his prone rest to play the gravedigger. In this last role he brought comic life back to a stage that, after its second intermission, was missing its strongest actors, both the prince (for a few scenes) and Polonius. The skullplay that followed was as broad as by this point we expected — since the second gravedigger was cross-cast with Ophelia, we even get a skull-as-baby-being-born gag — but Isaac’s Hamlet had by this point cleaned himself up, put black pants over antic undies, washed his face, and chastened his gaze. He even, when the poor Yorick speech briefly shifted into iambic verse, broke into song:

Imperious Caesar, dead and turned to clay

Might stop a hole to keep the wind away.

O, that that earth which longer kept the world in awe

Should patch a wall t’expel the water’s flaw. (5.1.202-05)

I tend to think that Hamlet’s sparrow-philosophy in act 5 is pretty thin beer and unable to account for the play’s violence. Isaac’s soulful delivery almost convinced me otherwise.

Not every part was as brilliantly played as the trio of Hamlet-Claudius-Polonius. Some reviewers liked Gayle Rankin’s Ophelia; I enjoyed the manic energy she put into the role, from binge-eating a massive tray of lasagne in act 2 to singing her mad songs in a “Skip to m’Lou” beat. But her lament for Hamlet’s loss of his powers — “O, what a noble mind is here o’erthrown” (3.1) — felt tepid. Her performance was emotionally opaque, which meant that when Isaac gushed, “I loved Ophelia” (5.1) in the graveyard scene, even in retrospect the relationship did not move. I loved Charlayne Woddard in Red Bull’s Witch of Edmonton in 2011, but her Gertrude never quite figured itself out. Roberta Colindrez and Matthew Saldivar were uncharacteristically sympathetic and memorable as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, but Anatol Yusef’s Laertes seemed a bit by-the-numbers.

In the play’s final clinch, Hamlet squirted poison into his uncle’s ear from a syringe (lots of syringes in this production), and the two dying men held each other up in a staggering embrace. Ritchie Coster had just taken his shirt off, which costume change usually signaled the shift from Claudius to Old Hamlet. Playing both good father and bad uncle at the moment that he’s killed by our prince, Coster’s final moment wasn’t especially subtle — yes, all the men in the Danish royal line really are murderous Machiavels — but this last turn was, after nearly four hours, quite moving. The two men loved each other and killed each other.

The Fortinbras foreign-policy plot having been excised, Key’s charismatic Horatio closed the curtain by claiming that he could “truly deliver” all the story of Denmark’s tragedy. I often spend classroom time on that speech, treating its summary of “accidental judgments, casual slaughters” (5.2) as a misreading of the play’s ambivalence about action. But in that moment, staring at the finally-still body of Oscar Isaac prone in rest position on the table, I felt convinced by this Horatio. He could, and the show had, truly delivered.

It’s sold out of course, but if you can finagle tickets before Sept 3, it’s worth the whole afternoon or evening!

Mr. Gold continues his wildly inappropriate “antics” with William Shakespeare, just as he did with Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller. Fortunately, Shakespeare’s play can, and has, withstood many directorial violations and shenanigans over the centuries but still manages to come through unscathed, the text overcoming virtually anything imposed upon it.