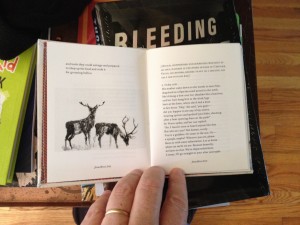

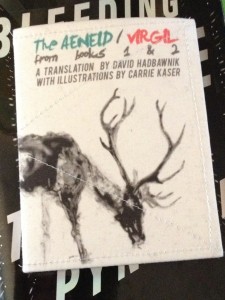

For the past week or two, I’ve been walking around with an imperial epic in my pocket. Gorgeous and hand-sewn, with an antlered stag leaning gracefully down on its linen cover, David Hadbawnik’s new translation of eight fragments from the first two books of Virgil’s Aeneid has been with me every day, walking the streets, teaching class, picking up the kids from school, even while I was attending and speaking at the fantastic Contact Ecologies symposium in DC. It fits nicely in my pocket. A little bigger than my iphone, but lighter and more flexible. More powerful, ultimately?

Is this the poem, Muse!, that launched a thousand empires?

I love Homer more, see more of Ovid in Shakespeare, and might well judge Dante the greater artist, but let’s not kid ourselves: Virgil’s the poet who made our world. Think about what’s hidden in my pocket right now: the poem of empire. All those imperial virtues and imperatives, piety, endurance, sacrifice, hard work and determination, the epic that turned the flames of Troy into the possibilities of Rome. In the slices translated here, our hero Aeneas wanders into Africa, fails to recognize his goddess-mother, shies away from heroic combat, eschews revenge on treacherous Helen, rescues his aging father but forgets his own wife. All for what? Italy! The future! Empire!

Reading Virgil always makes me feel split in half, divided between desire and duty, knowing that I should love Rome – think about everything that’s Rome’s done for me, for you, for all of us! – but not always managing to feel it. David Hadbawnik’s translation, and the fantastic chapbook-art object he’s co-made with the help of little red leaves textile series and the artist Carrie Kaser, brings that ambivalence home. Hadbawnik, a scholar of medieval literature, poet, and editor of two modern translations of Beowulf into experimental verse (by Thomas Meyer and Jack Spicer), engages the Aeneid with some of the time-shifting energy of Christopher Logue’s celebrated War Music, which slices up Homer’s Iliad with contemporary irreverence – Ares wears Nikes – and theological intensity – Logue calls Zeus “God,” as if his Homer were channeling Milton.

But in contrast with Logue’s raging semi-contemporary Homer, and perhaps also Meyer’s world-grappling Beowulf, Hadbawnik’s Virgil steps carefully, delicately, beginning by describing a precisely structured place of respite:

There’s a long inlet

where reefs strike out forming a harbor

waves break on either side of

huge crags that threaten the sky

but inside the sea, protected, lies still

so that

from high above it looks like the topmost

layer of trees gently waving in wind.

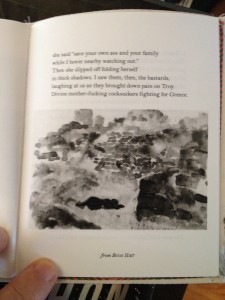

Lover of shipwreckful things that I am, I missed Virgil’s stormier opening, but I love the slow care of these lines of refuge, their on-high perspective, the “topmost” view that could only be that of Aeneas’s divine backers, and also perhaps of we happy readers. The tone is gentle like the tree-tops, “protected,” creating a safe space for Aeneas and for epic. Like the italicized Latin head-note quotations that preface each of the eight sections – “aequora tuta silent” opens the first one – these lines fashion a refuge for Virgil in modern verse. The language gets rougher – when Phyrrus finds Priam he “fucked him bent over the alter in front of / his wife and kids who ran slipping on the gore” – but my sense is that Hadbawnik’s crafting something like that poetic harbor for his modern Virgil. He’s not always throwing epic violence in our face in Logue’s manner but instead showing us how Virgil’s structures and values already live in our modern ways of looking at the world. Even when we want to resist them, these values are in our hearts, which is to say – in our pockets. Right there with this beautiful book.

The loss of Creusa, Aeneas’s Trojan wife, is one of the most painful moments in the poem. After turning away from heroic death in the ruins of Troy in order to save his family and household gods, Aeneas rushes back into the flames to seek his lost wife. He finds only her shade, who tells him – as all supernatural entities tell him – to get back to work, find Italy, found Rome. The future needs Rome! When I teach this moment, I talk about Aeneas’s slide into patriarchy, his choice of the male line of father and son over his wife. Hadbawnik’s translation, sitting here in my pocket right now, hits me with the tenderness of Creusa sending the widower back to work:

Sweet husband, why wait around grieving stupidly?

The gods made all this happen

Jupiter himself snatched me away in the bargain –

as for you, you’ll endure exile

plow the waves long and deep with your ships

till you reach Italy where rich fields

feed strong men and the Tiber flows through.

There you’ll find joy in a new realm and royal wife

So quit crying over Creusa, however much

You loved me….

RUN

and take care of our own little boy.

The burden of imperial destiny and the pain of exile, punctuated here by the all-caps line “RUN,” a fragment that shows up seven times in the five slices translated from Virgil’s Troy-burning Book 2, send Aeneas off toward Italy as a hollowed man, set upon a thankless task. The heartbreaking humility of Creusa’s “our own boy,” after she has just released him to faceless royal Lavinia, reaches for an emotional counter-space, a private human world for Aeneas the wanderer, who will go on to lose his fleet and need his mother to take care of him in Libya. “[Q]uit crying,” she tells our hero. Time for work.

The mother shows up briefly, Venus in hunting clothes, “O dea certe.” He doesn’t recognize her. We seldom recognize the goddess. “I’m one of the good guys,” Aeneas tells her, recounting his troubles. Venus doesn’t want to hear it: “Whoever you /are, the gods can’t hate you all that much. You’re / still breathing.” Is that divine petulance what Creusa burned for in Troy?

I love walking around with this epic fragment in my pocket. I like to read little bits of it when I’m on the train.

It’s the perfect holiday gift for all lovers of poetry and ambivalent creatures of empire.

Leave a Reply