I’m thinking about maritime know-how, metis, craft.

I’m thinking about maritime know-how, metis, craft.

My favorite of these words is Homer’s, metis, the particular kind of hand-knowledge and skill associated with Odysseus. It includes everything from sailing to boat- (and bed) building, not to mention fast talking. But it’s particularly associated with technical maritime skills and labor. It’s what Conrad calls “craft,” and what he thinks creates a bond among sailors. Some of the best writing I’ve seen on this topic comes in Margaret Cohen’s great recent book, The Novel and the Sea, which I e-reviewed on the Bookfish a little while ago, here. “Experience is better than knowledge” was the line I pulled out from the book, which Cohen took from Samuel Champlain’s manual on seamanship she does such great work with in her first chapter.

I’m wrestling with seamanlike metis, a set of tactics that improvisationally transform disorder into order, in a chapter of the book I’m writing on shipwreck from The Tempest through Robinson Crusoe. The metis chapter focuses on Jeremy Roch, a 17c mariner, amateur poet, and astrologer whose ms. journals are in the Caird Library at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich — a particularly wonderful place to do maritime research, by the way.

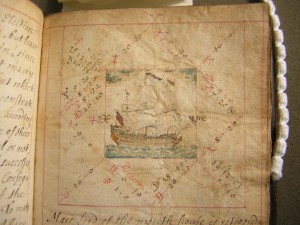

The picture above show’s an exploit Roch is espeically proud of: sailing in a open boat from Plymouth to London with only a boy and a dog, “one as good company as the other to me for any help I had need of,” as he notes.

Here’s a little snippet out of the current draft of the chapter —

Faced with disaster, sailors respond with work. Skilled, technical, hard to understand maritime labor becomes paramount in moments of crisis, which is why these episodes tend to fill with jargon. The Boatswain in The Tempest, whose lines provide the epigraphs for this chapter, provides a familiar example. His language interposes a host of sea-terms – yare, topsail, “room,” topmast, “bring her to try,” “main-course,” among others – alongside his resonant political and philosophic claims. While Shakespeare’s command of sea-terms was imperfect, he recognized the dramatic power of opaque, technical language in moments of crisis. The “cunning intelligence” and skill with technology that The Odyssey calls metis characterizes the core physical response of mariners to shipboard crisis. Metis is both a physical and an intellectual practice; it represents seamanlike labor and also an imaginatively-charged exploration of physical reality. As ships founder and rigging snaps, sailors struggle to maintain orderly forms of action and thought. The order-salvaging task of the sailor resembles the task of the shipwreck writer. Representing the jeitzteit crisis moment in poetic or descriptive language requires matching the physical labors of the mariner with the formal shaping of the writer. Performing metis requires hands, tools, and language.

Leave a Reply