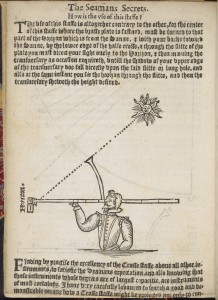

Odysseus the master-mariner was also a canny negotiator, clever talker, unscrupulous tactician, and hand-crafter of the Great Bed of marriage. His heroism captures a deeply hand-ed, not to say handy, way of working with things in the world, an embodied and physical knowing-how as opposed to knowing-what. The master of “cunning intelligence” and maritime know-how combines mental & physical practices, like John Davis, inventor of the Davis staff, navigator, and mathematician.

Odysseus the master-mariner was also a canny negotiator, clever talker, unscrupulous tactician, and hand-crafter of the Great Bed of marriage. His heroism captures a deeply hand-ed, not to say handy, way of working with things in the world, an embodied and physical knowing-how as opposed to knowing-what. The master of “cunning intelligence” and maritime know-how combines mental & physical practices, like John Davis, inventor of the Davis staff, navigator, and mathematician.

The Greek word for Odysseus’s kind of knowledge is metis, and one translation of this term in English maritime literature is “craft.” That’s Conrad’s favorite word for seamanship, as Margaret Cohen has explored nicely in her recent book.

Maritime literary studies can build on the basic homology between craft in the maritime context, a combination of knowledge, skill, performance, and social acumen, and craft in the context of poetic making and shaping. Recent studies of embodied cognition have been pushing back against hyper-intellectual and abstract culture of postmodern thought. Connecting “the way of a ship” — the complex mixing of social, physical, intellectual, cultural, natural forces into a constantly-errant voyaging body — to the way(s) of a poem seems a worthwhile task.

I’m working on a version of this overlap in two chapters of the Shipwreck book on professional mariners and amateur poets Jeremy Roch and Edward Barlow. It’ll also inform the lyric poetry chapter that begins with Donne’s “The Calm” and “The Storm.” The Bookfish itself is a physical and poetic object.

In Shakespeare’s Ocean I said I wanted a poetics of the sea, and I still want it. This will be one way to get there. First a poetics of craft, then a poetics of swimming, then…

Leave a Reply