Here’s a preview of the soon-to-be announced St. John’s English Deptartment Blog, for which most of the real work will be done by Tara Bradway and Danielle Lee.

Blackfriars Conference, Oct 2011

Here’s a link to a great Shakespeare and Performance conference, to be held next fall at the rebuilt Blackfriars indoor theater in Staunton, VA. It’s a replica of the indoor theater in which The Tempest was staged, and the conference includes lots of performances as well.

There will be performances of The Tempest, Tamburlaine, Hamlet, Henry V, and The Importance of Being Earnest during the conference.

Further sandy thoughts…

Jeffrey Cohen takes time out from his pending trip to Catalonia to respond to my repsonse to his beach thoughts, and say some nice things about my book.

I especially like the two-prongedness of his emphasis on beaches as spurs to physical activity (though he does not mention swimming), and also reminders of the relative weakness of the human bodies performing those activities —

If I say I find the sea calming in its agitation, that’s not because I sit at its edge with sun lotion and an alcoholic drink. For me the sea’s edge is for beachcombing, hiking, exploring. It’s a place of constant realization, of possible danger, of frequent reminders of death (empty shells, broken crabs, sea life suffocated in sand). The immensity of the sea reminds me of the small place of humans alongside its flow. Vastness gives perspective. That’s what I find calming: my own small agitations dissipate under those relentless waves, those sudden vistas and unexpected glimpses of life, all that noise so saturated with meaning it is chaos itself. Beautiful chaos, chaos as art.

I also like his thoughts on the “insinuating” quality of the ocean in shared human histories.

Calm, with agitation

Today’s bloggy text comes from that medievalist exemplar of academic blogging, Jeffrey Cohen (inthemedievalmiddle.com ). He was posting while on family vacation in Bethany Beach last weekend —

And is there anything more beautiful than the noise of the water upon sand? I was reading Michel Serres’s short book Genesis just before I left, and I keep thinking about his obsession with the creative spur that marinal disorder yields. I believe it. There is nothing so calming as the ceaseless agitation of the sea.

It may seem churlish to pounce on such musings, & I certainly love a trip to the beach as much as anyone, but I’m struck by the closeness of “calming” to agitation and to Serres’s “creative spur.” Do academics go to the beach to work, or to forget? I sometimes joke that I’ve structured my whole recent academic focus so that every time I go to the beach — and I live at the beach, albeit not a surf beach — it’s a work trip for me. But is that b/c I try not to be too calm when I hear oceanic noises?

Three things seems possible. Maybe all three at once.

First, our 21c experience of beachy calm is historically contingent, a function of our culture’s loss of the sea’s full terror and danger, partly b/c of the marginalization of sea travel & also, perhaps, because so many more of us are taught to swim reasonably well than was historically the case. I certainly think the “meditation” that Ishmael claims 19c New Yorkers connect with the sea in Moby-Dick is a more fraught thing than today’s calm recreation.

Second, writerly types like to conceal disorderly thinking under a calm facade, so that the agitation of the surf covers up the ceaseless churn of (imagined? inchoate? real?) intellectual productivity. Perhaps this is a happy fiction?

Third, maybe it’s our separation from the natural world, not any potential union with it, that “spurs” human creative work. The distance between us & the sea motivates.

Is it a different love than we feel for tall mountains or wildflowers or Tintern Abbey? I think it is.

A Question from the Woods

I used this image in my talk at Farleigh Dickinson today to talk about the purportedly living forest of Birnam Wood in Macbeth and, by extension, the dream of a green pastoral ecology — a place of natural stability and sustainability that can serve as a kind of model for human practices.

I used this image in my talk at Farleigh Dickinson today to talk about the purportedly living forest of Birnam Wood in Macbeth and, by extension, the dream of a green pastoral ecology — a place of natural stability and sustainability that can serve as a kind of model for human practices.

I then went on to talk about a “blue” or oceanic ecology based on change & disorder, using this image

As I was talking about these two visions of nature in the play, I admitted that they are caricatures or cartoons, but I also got a great question, after the talk, from a grizzly old guy who, apparently, hadn’t wanted to raise his hand in the full Q&A.

“I live in the woods,” he said. “It looks nothing like that picture. The woods are messy, chaotic, with things falling & breaking & dying everywhere you look. That picture isn’t a real woods. It’s something somebody planted.”

Sounds right to me. The green world, the green pastoral utopia that will heal all our ills, is a fantasy projection.

I suppose that implies that the blue world is too.

The Green and the Blue in Macbeth

As a quasi-reply to my first batch of student papers, here’s an offering of my own, a few paragraphs out of an oceanic reading of Macbeth that I’ve just finished. This version will be published in a Forum on “Shakespeare and Ecology” next year in *Shakespeare Studies*. I’ll be giving a slightly different oral version atthe Annual Shakespeare Colloquium at Farleigh Dickinson University in Madison, NJ, this Saturday at 1 pm. Come by if you’re in the area! It’s free & open to the public.

The ecological humanities have been drawn to Shakespeare in part because he’s the biggest fish in the Anglophone literary sea, but also because his long and living stage history provides tangible evidence of canonical texts engaging contemporary dilemmas. The current surge of ecocritical Shakespeare, however, risks seeing only the happier side of nature, a beach where the weather is always good. Sustained attention to the Shakespeare’s “green” should not occlude his dramatization of a harsher “blue ecology” that locates itself not in cultured pastures or even marginal forests but in the deep sea. Shakespeare’s literary works can’t get us all the way into this massive blue body – the most basic feature of the world ocean is that humans don’t live there – but they can serve as a fictive beach house, providing us with a beguiling window onto an inhuman space. The view from Shakespeare’s beach house shows the void next to which we perch our fragile bodies. It locates us right at the boundary which we can only temporarily cross. Like other beach houses, it’s vulnerable to coastal storms, and probably built on sand. It’s a place to which we return because of (not in spite of) the disorder in front of it.

Shakespeare’s dramatization of this inhuman, oceanic ecology appears in two intertwined tropes in Macbeth. The play’s “green” ecology imagines Scotland as a troubled agricultural land, husbanded by King Duncan, violated by the Macbeths, and eventually renewed by Malcolm. Against this now almost-traditional eco-reading, a “blue” ecological countercurrent exposes the play’s fascination with the inhospitable ocean. References to the sea teem in this land-locked drama. The bloody Captain analogizes battle to “shipwracking storms” (1.2.26); the Weird Sisters assail the merchant ship Tiger (1.3.7-26); and Macbeth himself rejects the “sure and firm-set earth” (2.1.57) for “multitudinous seas” (2.2.66). Even Lady Macbeth’s fantasy that water can wash away murder represents a fervent plea that the liquid element might serve human purposes. The play’s blue ecology combines the Weird Sisters’ inhuman perspective with the topos of the mind-stretching sea, which, as Auden observes, “misuses nothing because it values nothing.” The green and blue in Macbeth represent different visions of how humans live in the natural world, with green sustainability first displaced by Macbeth’s oceanic ambitions and then finally re-asserting itself after the tyrant’s death. For twenty-first century Shakespeareans living in an increasingly oceanic and disorderly world – the summer of this essay was the summer of oil gushing into the Gulf of Mexico – supplementing green narratives with blue incursions feels urgent.

What we’re looking for

I wrote, with a little help from Shakespeare & Melville, about the sunken treasure that’s at the bottom of all of our literary excursions in Shakespeare’s Ocean —

They wink up at us from the depths, skulls with be-gemmed eye-sockets, wedges of gold, encrusted anchors, heaps of pearl. Fish-gnawed men and what’s become of a thousand fearful wracks. Treasures of the slimy bottom. Captives of the envious flood. What we’re looking for.

I’ve been thinking about those slimy treasures while reading my students’ essays this week.

The hardest thing about literary & literary-critical writing in any form — and I’m pleased to see a very wide formal range in these papers, from pedagogical plans to theatrical outlines, intertextual readings, and archival historicism — is trying to make sure you get down to some real and meaningful bottom, even while knowing you’re not likely to reach firm ground. Often in reading these papers, which are of course just early drafts or hints of what’s to come, I wanted you to dive deeper, to press harder, & to make a lunge at the analytical or pedagogical or creative pay-off that seemed just out of reach. There’s a certain recklessness and risk in literary writing — there’s no real way to be sure of what Shakespeare meant, at this historical remove, just as there’s no real way to be “sure” of any literary text. I’d like to see more risk-taking, and more self-aware speculation about risks & rewards, in the final versions of these papers.

I’m looking for papers & projects that get us a little bit closer to that ungraspable bottom & its glittering treasures. But I should remember, as I also wrote

It’s to the bottom of Shakespeare’s ocean that this book takes you, except for one thing: we never get to the bottom.

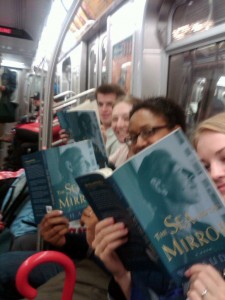

Auden on the Subway

Julie Taymor’s Tempest

The trailer for Taymor’s forthcoming sound-and-lights extravaganza Tempest is now on YouTube:

It’s supposed to open Dec 10. Maybe the class should all go together on our last night, 12/14?

Thanks to Tara for the link.

Update: Watched it again today & it looks fun, if perhaps a bit over-the-top. Sorcery. Passion. Stupidity. Treachery. Revenge — so go the subtitles. An interesting summary, I suppose?

We certainly should go on 12/14. Anybody know a movie theater close to campus?

All is need and change

Caliban’s long speech in Chapter III of The Sea and the Mirror (channeling Henry James, as Ashbery’s blurb has it) is a bizarrely counter-intuitive performance of the “natural” in Tempest-ville. It’s also deeply, subtly, a meditation on the dramatic Muse, explicitly so in the italicized part at the start. There’s also some hard-to-follow movement of the pronoun “He,” which seems to stand for Ariel, Caliban, and Prospero at different time. Perhaps our friends at Cutting Ball, currently rehearsing a Tempest w/o either Ariel or Caliban, want to weight in on that slippage?

My favorite passage isn’t the “restored relation” at the end, but the passing hymn to radical difference & change that comes on p47: “the wish for freedom to transcend any condition,” which may be a kind of “nightmare” or also “a state of perpetual emergency and everlasting improvisation where all is need and change.”

Recent times, and political theorists from Schmitt to Agamben, have suggested a political reading of that state of emergency as well.