Though I’ve been beaten to the punch by Jeffrey Cohen, I wanted to post about the Sustainability cluster in PMLA. And maybe a little bit about the eco-issue more generally.

What strikes me most about reading this issue is how wide a range of meanings sustainabilty has.

There are three main modes in these essays: institutional (Alaimo, LeMeneger and Foote), literary (Brayton, Keller, and me), and critical (Nixon and Zimmerer). There’s some overlap in a few of the pieces, esp. in Keller’s which covers both institutional and literary material, but less than you might think.

There are three theorists who many of us invoke: Latour, master of assemblages, Tim Morton, ecologist without nature, and Ursula Heise, theorist of localized globalism.

Here’s what I think we think:

Stacy Alaimo: Writing out of her experience as academic cochair of the Sustainability Committee at UTA as well as posthumanist theorists of trans-coporality, Alaimo sees sustainability as a “sanitized” corporate term, “frequently invoked in economic and other news stories that do not in any way question capitalist ideals of unfettered expansion” (559). She wants humanities scholars and scholarship to displace this “technocratic, anthropocentric perspective” (562) — and she wants the new materialism about which she, and others, write so well.

Dan Brayton: One of several of us who explore sustainability through literary “narratives of…catastrophe,” Dan turns to Peter Mathiessen’s experimental novel Far Tortuga, an old favorite of mine as well. It’s a compelling, tragic, artistic response to “an apocalypse that [has] already happened” (370).

Stephanie LeMenager and Stephanie Foote: Turning back like Alaimo to practical and administrative questions — the cluster as a whole see-saws between poetics and administration as thematic cores — these authors ask that humanities scholars contribute to the dialogue, perhaps via a new term, “the sustainable humanities.” “At the risk of sounding grandiose,” they write, “Earth needs the humanities” (575). They also write movingly about classroom practice, that secret heart of activist pedagogy: “literature models new wells of collectively understanding the possible” (577).

Lynn Keller: While noting that “sustainability is everywhere these days” (579) — even in PMLA! — but it’s often subsumed by capitalist models of expansion, she asks humanities scholars to help reclaim the term from the “blurry, feel-good realm of corporate advertising” (581). Like Brayton, to some extent, she sees value in tragic forms, in this case “environmental apocalyptic writing” (581) like Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, Tim Morton’s “ecology without nature,” and the contemporary poetry and art of Ed Roberson, Angela Rawlings, Evelyn Reilly, and Juliana Spahr, none of whom I’d known before reading this article.

Steve Mentz: [I may come back to my article at the end — basically, I ask that we stop being boxed in by fantasies of sustainability: “It seemed like a good idea while it lasted, but we should have known it could not last.” I mostly talk about literary questions; perhaps showing my early modernist roots, I think sustainability is another version of pastoral.]

Rob Nixon: Doing a job that’s long needed doing, this article exposes the influential “tragedy of the commons” model for the neoliberal polemic that it is. Suggesting that Hardin’s thesis relies on literary forms — tragedy and parable — for its political force, Nixon suggests that rejecting this model for a more nuanced notion of governance of the commons, via Nobel Prize-winning economist Elinor Ostrom, can reframe political notions of sustainability so that the villains are no longer old-fashioned collectivists but “unregulated, voracious emissaries who have no respect for limits and no sustainable, inclusive vision of what it means, long-term, to belong” (598).

Karl Zimmerer: Probably the most unusual article in the cluster, this article approaches sustainability through the untranslatable Native American term “kaway,” which might mean “established way of life” or “customary diversity” (601) or, perhaps, something better than what we now mean when we say “sustainability.” Arguing that Quechua philosophical frameworks lack the “separteness of nature and culture in classical traditions of modern Western thought” (603), Zimmerer suggests that kawsay can reeducate us, such that we see “an ideal of nature as humanized landscapes of indigenous food-producing environments and technologies” (604), rather than any full separation of nature from culture.

I’d add to the mix Tobias Menely’s great article on Cowper and “the Time of Climate Change,” because I think he comes at sustainability from the other end, by way of crisis. Like Brayton and Keller (and me), Menely juxtaposes catastrophe experience against fictions of sustainable stasis — and does not assume the latter must always win.

The question remains: what next? What happens “after sustainability,” to repurpose my own title? I certainly hope, like Alaimo and LeMeneger and Foote, that humanities scholars can reclaim eco-speak from capitalist and corporate lexicons — and I think that, esp. in our capacities as faculty, administrators, and organizers inside and outside academia, we can help move that needle, to some extent. I also think, like Brayton and Keller (and Menely), that tragedy speaks most richly to this project, though, like Nixon and Zimmerman, I agree that we should not accept existing economic/cultural models, and we should not be shy about promoting non-traditional alternatives.

But still: what do you do inside an ecological catastrophe? That’s the question I think we need to work out, the question I’ve been burrowing into at least since “Strange Weather in King Lear.” How do you live inside the storm?

I don’t have a terribly good answer in the institutional or critical modes, at least not yet — though I think para-academic pressures and non-Western critiques can help a lot. But I have been looking for a while for a “swimmer poetics” to help on the literary side. A couple paragraphs of this appear in the PMLA essay. More to follow —

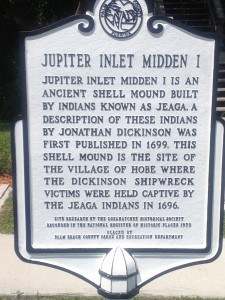

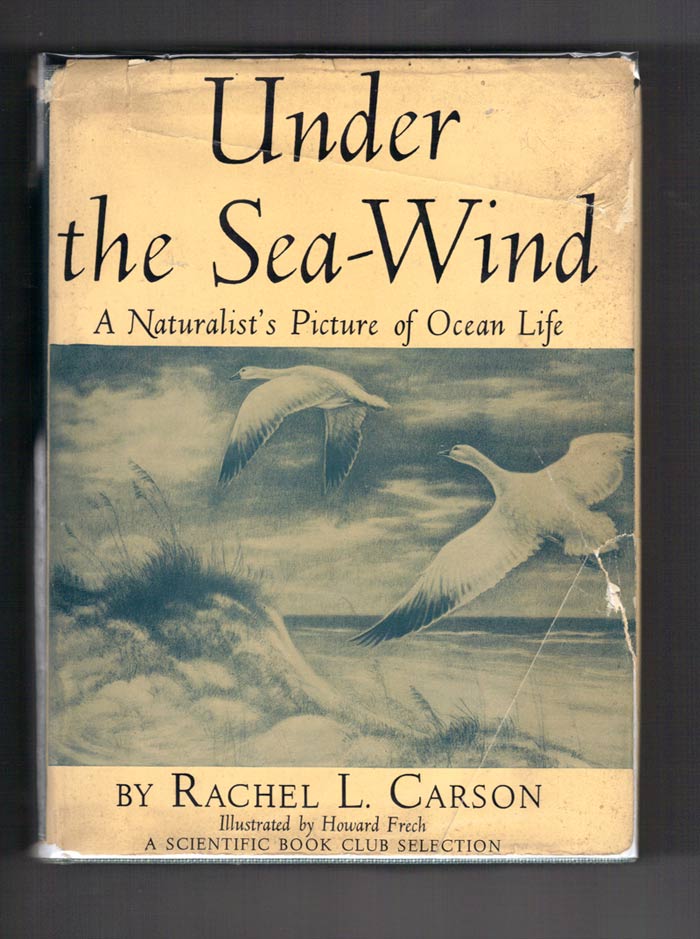

I have been listening to Rachel Carson’s narration of the coastal Atlantic ecosystem this afternoon while driving back to my parents’ house near Jacksonville from

I have been listening to Rachel Carson’s narration of the coastal Atlantic ecosystem this afternoon while driving back to my parents’ house near Jacksonville from

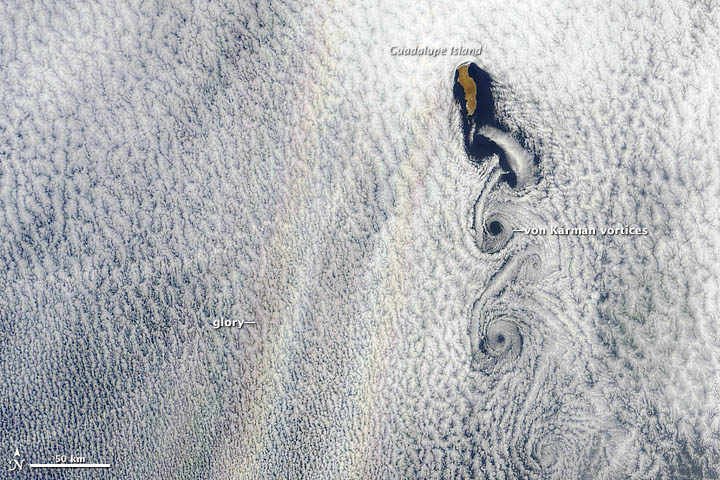

It may look like a cloud-rainbow, but it’s a “

It may look like a cloud-rainbow, but it’s a “