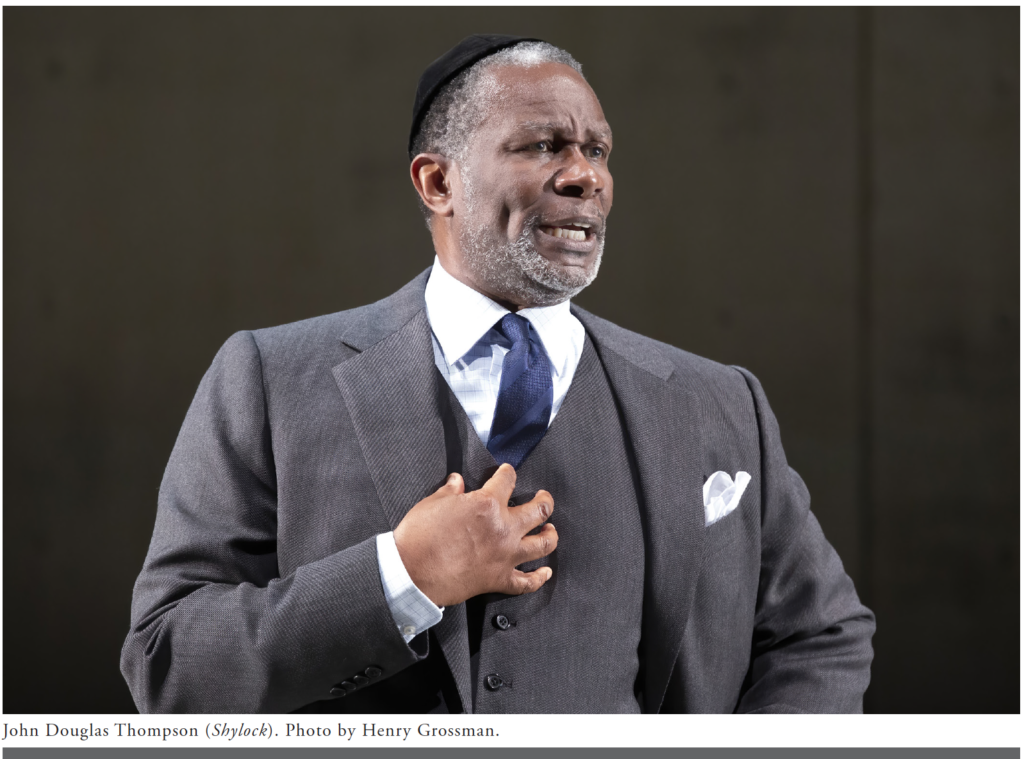

Sitting in the almost-full confines of the Polonsky Shakespeare Center in Brooklyn, watching John Douglas Thompson’s towering performance of Shylock, I felt the thrill of being back in the theatrical moment, feeling actors’ words and director’s vision radiating out across seated bodies. Like Alexis Soloski, who gushed in the New York Times that Thompson is “perhaps the greatest Shakespeare interpreter in contemporary American theater,” I’ve been a fan for years, from his Satchmo at the Waldorf in New Haven to a recent Broadway turn as Kent in King Lear. Maybe his Tamburlaine, which I also saw at Theatre for a New Audience back in 2014, was the high point for me, as I sat in the front row and got stage blood-splattered.

The innovation of director Arin Arbus’s 2022 Merchant casts the play’s Jews with Black actors. As Ishmael Reed notes in the Tfana 360 program, this casting isn’t simply playful or cynical, but rather explores meaningful “parallels between the experiences of Jews in Europe and Blacks in the United States.” Thompson’s Shylock rages and cries and insists on his own centrality in the manner of a tragic hero, and Arbus’s dark and incisive production continues the tradition of playing this supposed comedy through its tragic notes. (Recent productions in this mode include Karin Coonrod’s extraordinary experimental version, first played for the 500th anniversary of the Jewish Ghetto in Venice, which I saw at Yale Law School in 2018, and a shocking production by the all-male troupe Propellor that came to Brooklyn in 2009 and featured Shylock attacking Salarino before the “Hath not a Jew eyes” speech.) It’s hard for the other actors, or the Portia-Bassanio marriage subplot, to compete with the high drama of the fall of Shylock as father, moneylender, Jew, and center of our attention.

For me, the most searing moment in Thompson’s performance came shortly after his famous speech insisting on his humanity, his eyes, his “hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions” (3.1). Eagerly seeking news about his lost daughter from his fellow Jew Tubal, played by Maurice Jones (who also has a wonderful comic turn as the Prince of Morocco), Shylock learns Jessica had given a turquoise ring she stole from his house to a merchant “for a monkey” (3.1). Thompson’s delivery of the story of that ring — “I had it of Leah when I was a bachelor. I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys!” — opens up the vast human history behind Shylock’s pride and devotion. I especially loved his emphasis on the word “wilderness,” exposing the brutality of one of Shakespeare’s most insistently urban plays.

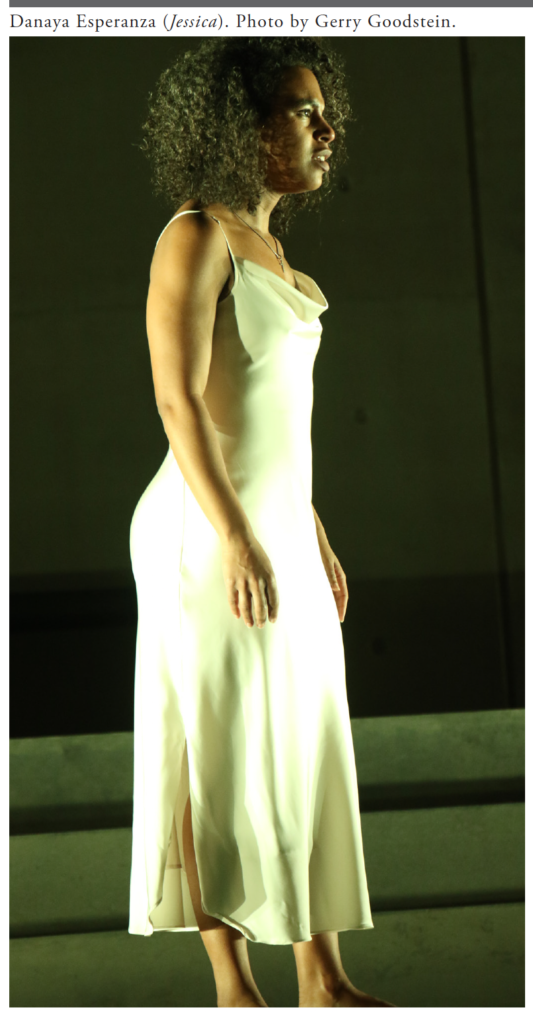

Beyond Thompson’s Shylock, the unexpected second star of the production was Danaya Esperanza as Jessica, the Jewish daughter who abandons her father’s house and religion, carrying off his ducats, his ring, and his (symbolic) jewels. Matched to a loutish if good-humored Lorenzo (David Lee Huynh) but more closely connected to the wonderfully goofy and mobile servant Lancelet Gobbo (Nate Miller), Jessica ends up painfully isolated, stuck as all the other married couples are stuck at the play’s end. Her line readings were excellent, but the role came through most strongly in some carefully crafted silences — embracing her father one last time before she elopes from his house (2.5), laughing cozily with Gobbo as they share a pipe in Belmont (3.5), standing pointedly far from Lorenzo during the long final scene (5.1). Her motivations for leaving her father are seldom clear, and Huynh’s Lorenzo seems more party boy than true lover. To make her way in Venice may require her to steal out of Shylock’s isolation, but despite her marriage and incorporation into the party in Belmont, she remains conspicuous, the lone Black body on stage for almost all of 5.1.

The cast of the love plot was lively if unable to match the high drama of Shylock and Jessica. In fact, Jessica’s decision to move from her father’s world to her husband’s might be thought of in generic terms, as an attempt to leave tragic isolation for comic solidarity. If so, the play reminds us that integration has been a culturally fraught process for Jews as for African-Americans. But one other figure who sits astride the two plots, Lancelet Gobbo, might make an interesting bridge. Played with verve and goofy humanity by Nate Miller, Gobbo as Clown moves, like Jessica, between Venice’s Jewish and Christian worlds. This production does not take up the text’s few hints that Gobbo might be Muslim – Shylock calls him one of “Hagar’s offspring” (2.5), and he later gets berated by Lorenzo for impregnating an offstage “Moor” (3.5), who may be Muslim as well as African. But the servant Gobbo clearly connects to Jessica more closely and intimately than does her upper class Christian husband. Gobbo carries letters between her and Lorenzo, and in a slightly strange interpolation he shares a vape with her after she has run away from home (3.5). Lorenzo, whose aggression spills out both in this scene and every more uncomfortably in an interrupted sexual clinch with Jessica in 5.1, recognizes Gobbo as a kind of rival for Jessica’s affections, or at least for her understanding.

Years ago, I wrote about Gobbo as a figure for the economic middle-man, who parodies and challenges the economic theories of exchange, hazard, and abundance that dominate the main plots. I remember writing the first draft of that essay in January 2001, right after my first child was born; my exploration of Gobbo’s critique of Antonio’s mercantile world, Portia’s fantasy of wealth, and Shylock’s financialization came into being amid a noisy and exhausting period of sleeplessness and colic. The essay, which eventually was published in Linda Woodbridge’s collection Money and the Age of Shakespeare in 2003, was one of my first publications on Shakespeare. I still think more could be said about Gobbo, and I was pleased to see Arbus’s production cultivate his peculiar position between and across the social, religious, and racial boundaries of Venice.

For modern productions that emphasize Shylock’s fall, the final scene (5.1) can feel pretty bleak. All three married couples are back in Portia’s opulent Belmont, but the husbands Bassanio and Gratiano have given away their wedding rings, Jessica and Lorenzo can’t stop talking about errant classical lovers, and in this production they pointedly don’t stand near each other for the whole long scene. Portia’s sleight of hand fixes the problems, as her courtroom hyper-literalism saved Antonio from Shylock’s knife, but it’s hard not to see in the solitary progress of the characters offstage a future that’s at least as constrained as the life Jessica had led in Venice.

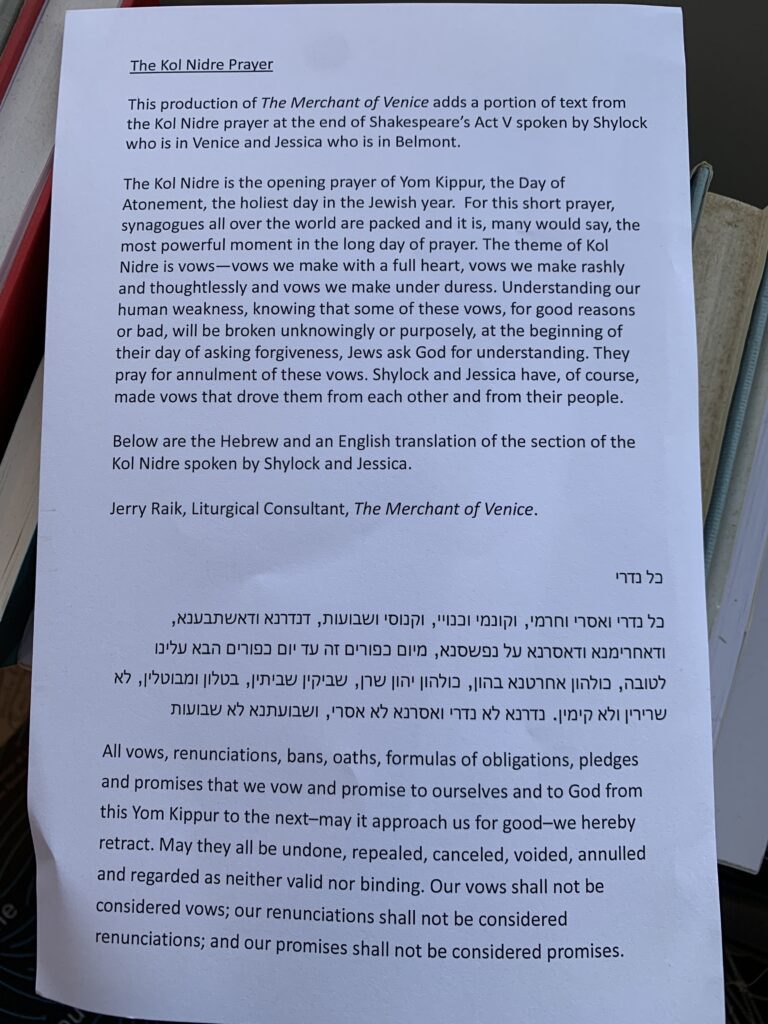

Except Jessica doesn’t go off stage. She stays, alone, until – in a wonderfully overt intrusion onto Shakespeare’s script — John Douglas Thompson’s Shylock returns. He does not embrace his daughter, and in fact they appear not to see each other. The production does great work throughout with characters refusing to look each other in the face; Antonio avoids Shylock’s gaze and refuses his handshake when they first make their bargain (1.3), and all the Christians avert their eyes as the broken Jew agonizingly packs up his bag and exits the trial scene (4.1). In this final extra-textual moment, Jessica and her father may not see each other but instead they share a Hebrew prayer, the Kol Nidre, which opens Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. The final curtain comes not on Gratiano’s last dirty joke about his wife Nerissa’s ring, or even on the uncertain future of the marriages. Instead, Arbus draws our attention to the separation but perhaps also the lingering connections of father and daughter, he forcibly converted in Venice and she voluntarily in Belmont.

I love modern productions that take risks in order to make visible things that are only hints in Shakespeare’s copious language. In some ways I’m still puzzling this final choice, and thinking also about the difficulty that modern productions have in creating anything like comic closure in the play’s final scene. Does the imagined reunion of Shylock and Jessica serve to re-animate a different kind of comic redemption? Or does it more simply return to a grateful audience the central star who has otherwise been painfully absent during the last long scene?

Things to think about! Go see it in Fort Greene before it closes on March 6!