Before I scatter the still-smoldering fragments of the co-created Lexicon of #CreatingNature, I want to make a stab at what I’m taking away with me. The hours since the conference community dispersed from DC have been wonderfully intense. The maelstrom of my son’s high school graduation produced overflowing cross-currents of family, friends, and worlds in the process of changing. What are the things that last, as everything changes and ripens? What do we get to keep?

So, quickly and incompletely assimilated: this weekend’s events have created in me a phrase I hope never to forget: Everybody’s infrastructure all the time. The mash-up buzzed into my mind’s ear sometime after Ian received his diploma on Sunday morning. It’s been rattling through my imagination ever since.

Conference-goers and twitteristi may recognize the terms I’m combining. Lindy Elkins-Tanton, the scientist who took some time out from her project of sending a spaceship to the metal asteroid Psyche and building the Interplanetary Initiative at ASU to co-deliver our keynote, gave us the core: “Everybody is invited all the time.” To build things, and to rise to planet-sized challenges, she reasons, we need everybody together. It’s an audacious, inspiring, wonderfully plural vision.

The added word infrastructure comes from another of the conference’s distinguished guests, Michael Dove from Yale’s School of Forestry and Environmental Sciences. He talked about cultural infrastructure: the protocols, practices, stories, and conceptions of order through which human societies manage proximity to environmental danger. His example unspooled the cultural logic of small Javanese villages high on the slopes of the very active Merapi volcano, but the larger implications for a hotter and more violent global climate resonated powerfully, especially when we saw young climate protesters stretch out their bodies on hot concrete in front of the Supreme Court. We need new cultural infrastructure to live in the Anthropocene. Volcanos, Michael said, are “world making.” I wonder what cultural worlds are being made and destroyed today.

The last bit, all the time, also comes from Lindy. The words speak to collective action in the face of the multiply moving and disjunctive time scales of the Anthropocene. Can we imagine “all the time”? What sorts of futures and pasts and abrasive presents get collectivized in that phrase? Lindy also spoke about a 30-year project, like her mission to Psyche: what’s the thing you want to do in and for the world, especially if it takes you the rest of your professional life? I don’t yet have a good answer to that one yet. But I’m looking!

Everybody’s infrastructure all the time. I keep circling around the idea. We want infrastructure for everybody, and also everybody is and must be that infrastructure.

But first, before the fire cools, some more on/from/with #CreatingNature.

Creating

Academic symposia generate crossings and crossroads, and we pass through them to discover ideas that spring up like the Spontaneous Urban Plants Nancy Nowacek described caring for in post-industrial Brooklyn. Riding the train north on Saturday morning, sleepy and disoriented from after midnight Dark ‘n Stormies with Jeffrey, Lowell, and Erin, I felt the overflow. So many flickerings dancing through my head!

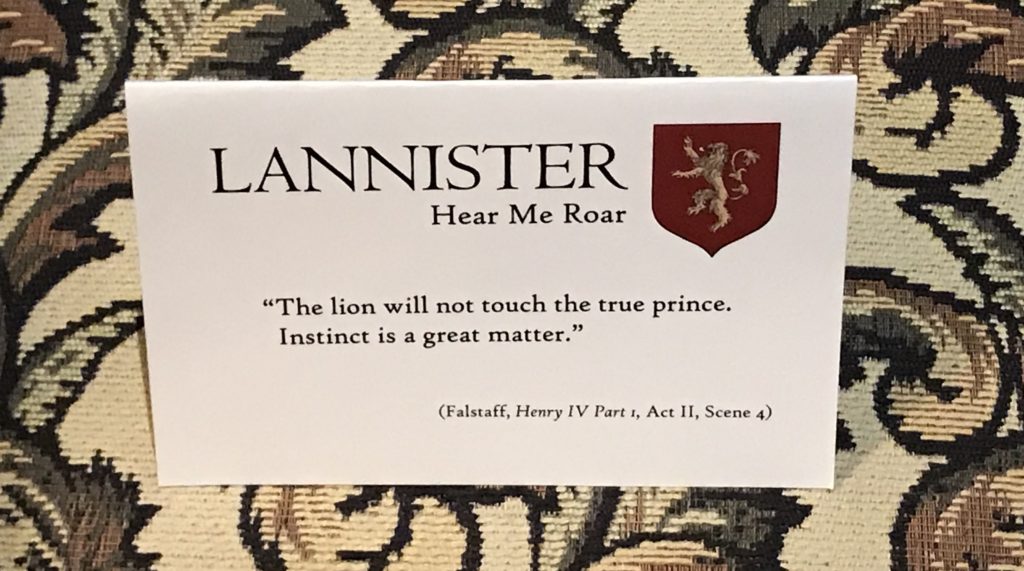

Some of the lexicon has already been e-immortalized via the twitter hashtag #creatingnature, but I also want to frame these words and thoughts in dialogue with our Shakespearean title and the Nature that’s creating us as we are creating and re-creating Nature.

The great goddess Natura and English word Nature conceal powerful tensions and fantasies, from natural philosophy to human nature to the interlocking structures of influence that gave rise to the word “ecology” in the nineteenth century. Nature is an imagined unity with which (some say) we must dispense, since Nature should not be separate from culture or Art or other human-generated phenomena. Thinking Nature points us into physical space, toward objects in spaces, spread out across and around our physical worlds. Nature produces the frictions and feelings that we worked so hard to represent last week.

But as I tried to catch in words during the Closing Roundtable, the Shakespearean modifier “creating” also hurls Nature into time. It’s the disorienting meeting of place and time, Nature and creation, that generates shared and shareable narratives. “Creating” as agentive principle asks us to recognize that the things we love will change, that they will graduate high school and leave our shared homes. Things we fear or hate or struggle against will also change. Change underlies and unsettles and makes uncertain. Creating cultivates the feeling that the ground under our feet may open up or is always opening up, so that falling into novelty is more norm than exception. “Creating” as first principle of errancy, in this sense, connects to a post-sustainability or dynamic ecology, something that I first wrestled my way into thinking about by writing almost a decade ago on this conference’s favorite literary touch stone, Lear in the storm.

Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks!

Creating Nature, says the mad old homeless king, hurts and confuses and wets us “to the skin.” He responds with a lyric howl. In response to that inhuman abrasion, we (academics and teachers and word-people more broadly) need lexical tools.

Here are some of the tools we gathered at the Folger last week, and some thoughts about how we might use them. Apologies for taking a bloggy and sloppy attitude toward citations in what follows!

Being a list of lexical tools for/from Creating Nature, including some fantasies about their future Uses

Session 1: Sustenance

Karen Raber opened us up with the proper ambivalence toward food for the body and narratives to sustain imagination. What sustains? At what cost? Who’s listening? Who’s eating what?

Counter-pedagogy: Right from the start I had the sense that the things we were seeking wouldn’t move in only one direction. Julian Yates described Lear’s response to the Noah story as counter-pedagogy of dislocation and alienation, which turned the idea of narrative as sustenance toward less comforting places. “Survival is insufficient,” he quoted from Station Eleven, suggesting that we worry ourselves beyond simple preservation toward things slippery and monumental. To create an Ark entails preservation through radical isolation — just so many pairs of creatures and no more. Julian and Jeffrey’s refuge-focused re-reading of Noah pushes us into the rain, where counter-stories flourish and, at least for a time, swim.

Parasitic opportunism We were a bit nervous as nine o’clock struck and we were still one speaker short, but Dagomar Degroot successfully navigated both cross-town traffic and the volatile sleeping habits of his newborn baby to offer a brilliant tool-word via his reading of the Dutch Republic’s Frigid Golden Age, which leveraged the Little Ice Age to the small nation’s advantage. During his fantastic talk, I had the queasy sense that the geopolitical advantages of today’s climate crisis may also support Arctic nations, through increased access to fossil fuels, trade routes, and agriculture — which may somewhat explain Russia’s recent resurgence, though in fairness the community of Arctic exploiters also includes Canada and the USA. To seize the opportunities of parasitism sounds both enticing and likely corrupting.

Aquaculture Maritime environmental lawyer Robin Craig’s great overview of how fishing has created (or re-created) the modern ocean gave rich context to the “shifting baselines” problem in environmental history, in which each generation’s scarcity gets reimagined as a new normal. Thinking about her gestures toward a global history of aquaculture, I was struck by “culture” as both physical and conceptual substrate, a medium in which things and ideas grow. Might the vertical oyster cultivation that thrives on a local scale on the other side of my little Connecticut town presage aqua-cultural changes yet to come?

“To ark the ocean” Building (I think) on Jeremy Jackson’s keynote at the Oceans Conference she had co-hosted in Utah this past February, Robin performed the interdisciplinary move the conference was designed to facilitate when she spliced her thinking about fishery management into Julian’s ark-visions. I loved this moment because the great hope I had (and have) for #creatingnature is precisely this sort of crossing, in which a marine environmental lawyer jumps on board with a literary project and thinks together about (to borrow one of Lindy’s phrases) the biggest things we can do. Why shouldn’t the ocean be our Ark?

Session 2: Storms

Joe Campana offered three poetic storm-aphorisms on which I’m finding much post-storm sustenance:

Storms endure.

Storms create ( or”write”).

Storms expose (systems).

Storm Time Kellie Robertson may not have known it but the clock was ticking and the storm heading our way as she outlined a series of “geostories” regarding a fatal lightning strike on an English church in 1652. Each successive account opened up new gaps from first-hand experience and titled toward new ideological warnings and calls to action. “All things come by Nature,” wrote one post-storm recap, including perhaps the Anglo-Dutch Wars and perhaps even the English Civil War. Storm Time and narrative time represent, in Kellie’s intriguing metaphor, a setting which frames, displays, and perhaps (mis-)interprets the jewel of experience. Storms are story-makers, writers, exposers, witnesses, Joe had already reminded us.

“Shipwreck years” Valerie Trouet’s triple archive of trees rings from the Florida keys, meteorological data from the eighteenth century, and the records of shipwrecks from the Spanish flota enabled a deeply persuasive story about shipwreck years punctuating the variable climates of the Little Ice Age in the early modern North Atlantic. I’ve loved this project ever since it was described to me by my cousin-in-law Noah Diffenbaugh, a paleoclimatologist at Stanford who knew about my literary work on shipwreck and wondered how it might interface with Valerie’s analysis. It’s not a simple fit. She uses the collected records of Spanish shipwrecks as a proxy for water temperatures in the Caribbean, while I explore individual tales as narrative responses to environmental hostility. There’s a numbers problem: I explore a lot of fictional and real shipwrecks in my book, but not nearly enough to draw statistical conclusions. But in some ways even more intriguing to me were Valerie’s reading practices, not of texts but of trees. Her tree-ring lab in Arizona comprises a practice of technical close reading, an engagement with natural codes and patterns legible in the trees that she does not harm in her practice, as she was careful to remind us. Like many humanists, I sometimes feel swamped under all the books I don’t have time to read. But what about texts that aren’t obviously books? How much remains to be read in what was once called the Book of Nature? I want to open my whale’s throat to learn all the languages of all the creating creatures.

Experience Henry Turner was one of several English professors who noted his own critical identity on the margins of a rising tide of self-professed eco-profs — and then Henry, like Debapriya and Liza later, contributed some of the most potent ideas and terms of the event. Henry came to experience via John Dewey’s pragmatism, and also via a line I quoted some years ago from the early modern French mariner Samuel de Champlain: “Experience is better than knowledge.” The original French is better:

L’experience passe science.

I ventured my semi-coherent French vowels to Valerie during one of the many breaks, suggesting that the mariner’s language values the claims of experience’s practiced hands over science’s rational head. “I don’t know about that,” Valerie said, in a very reasonable defense of science.

Of course we want and need and use both experience and science, the rational claims of thought and the instinctive feel of a skilled hand on the tiller. But I take Champlain’s point, and I think also Henry’s, to indicate a mystery at the heart of experience that hyper-rationalism, including the rationalism of all academic practices, occludes. It’s very hard to (in another of Henry’s phrases that I hope I’m not garbling) “feel what it feels like to be thinking.” Thinking about experience asks us to feel that thinking.

INTERRUPTION: TORNADO WARNING! Melville’s Ahab insists on being, in the middle of the personified impersonal, a personality. We experienced, in the middle of the session on storms and time and experience, a storm. Huddling in the basement and the room where they store theatrical costumes jerked us out of the formal conference. It suddenly re-assembled us into unplanned conversations, responses to proximity and anxiety and not-knowing what the storm was doing outside, except via the glowing proxies of our phone-radars. I always want to run out into storms, Lear-like, and encounter their vastness with my body. I’m glad I’ve learned to listen to wiser voices at such times.

Distraction In Henry’s reading of Dewey, experience struggles against distraction. Thee disjunctive side-step of the tornado was both distraction and jump-start. “Did we just experience climate change,” Henry asked as we filed back into our seats. Single events are only weather, not climate, several people noted — but what if climate change was not the tornado but the warning, not the storm but its over-writing and infiltration of our professional event? Does what we know about a post-Natural climate or “no analogue state” provide an interpretive tool with which to read the tree-ring accumulations of weather into a new human/inhuman language?

Co-Plenary: Climate / Weather / Feeling

Aspirational humanism We eco-humanists have been worrying about the human for some time, and ideas of the post-human and even post-humanities have staked out meaningful claims in our discussions. That’s all the more reason to value Lindy and Jeffrey’s co-plenary declaration of hope and aspiration for human accomplishments. I suppose if you’re leading a multi-year space mission to the asteroid Psyche it pays to thing expansively — Psyche is something like 200 million miles away — but I also appreciated the invitation inside my favorite library. What is the big thing we want? I love conferences and books and phrases and brilliant lectures in the Paster Reading Room. But maybe there are bigger things?

“Everyone is invited all the time” Lindy’s marching orders about inclusion emerge from her Interplanetary project, and I suspect also from her collaborations with Dean-Gandalf interlocutor Jeffrey Cohen. I love the audacity. Everyone! All the time! In a world of universities with scarce resources and academic cultures that value selectivity, aggressive access has the flavor of myth. What if we can build a spaceship Ark Ocean big enough to invite everyone? What do you call an Ark without an outside? Can we think insides without outsides?

Session 3: Shelter

Jen Munroe and Rebecca Laroche re-started us on day 2 with an OED-fueled exploration of shelter as military technology and, surprisingly, tool for conflict. They also pointed us toward the International Climate march that was happening that morning in front of the Supreme Court and elsewhere around the globe.

Cultural infrastructure Michael Dove, who was heroically struggling with a cold, presented his research on the cultural life of Javanese villages high up on the slope of the violent Merapi volcano. In his telling, the imagined “spirit village” that lives inside the crater and mirrors the human village on the slope represents a fictional stability, a way of living close to destructive forces. Volcanos, which are among the most consequential forcing agents in pre-industrial climate change, also generate fertile soil and, perhaps because of their danger, a partial respite from the “hydraulic state” that controlled the labor and lives of lowland Javanese peasants. To domesticate the volcano and transform it from threat to “world-making agent” and “interlocutor” represents a cultural gambit, a making-legible of a fiery violence that makes even trees and the ocean seem relatively tame.

Surrender Debapriya Sarkar’s moving evocation of shore as partial shelter in early modern literary romance balanced Michael’s reading of the volcano. Sea against mountain, water against fire: both hostile elements that lure, destroy, and stimulate the imaginations of those who live alongside them. Like many, I was especially struck by the last word of her talk, “surrender,” which upon discussion spoke to many our own memories of the experience of coastal storms, as well as to Debapriya’s personal response to the recent elections in India. Both talks in this session worked to “culturize” climate (to adapt a phrase of Michael’s) in the sense of recognizing the interstitial work that cultural forms, mythic and narrative, do whenever humans live near hostile environments they know to be violent but yet remain deeply desired.

EXCURSION: CLIMATE PROTEST

The young protesters lay on the hot sidewalk in front of the Supreme Court:

“You will die of old age / We will die of climate change.”

“The seas will rise, and so will we!”

I was glad to be there to see them.

Session 4: Spirits & Science

Anne Harris introduced our final session on “Spirits & Science” with a nod toward plurality and a celebration of the possibilities of slippery surfaces and encounters.

Slippage We all held our breath as Lowell Duckert told the tale of Balmol (sp?), a 17c Dutch explorer whose glissade launched him off the glacier into the Arctic Sea — though he seems in the end to have surfaced and returned to his ship. Nancy Nowacek elaborated the slippery path of her Citizen Bridge project, about which she wrote from Oceanic New York back in 2015. So many slippery surfaces! So many fortunate and frightening encounters!

Habitat compensation Nancy’s depiction of Habitat Compensation Island, built outside the industrial port of Dubai, got us thinking about what “compensation” means in cultural terms. Robin reminded us that compensation describes a legal remedy, and also that marine environments tend to repair themselves more efficiently than terrestrial ones.

“Nature has no end” Liza Blake’s reading of dramatic stoicism in George Chapman’s plays sounded out a bass note of inhuman affinity: what if the ecologically just thing to want is to become soil, to feed the grasses that feed the cows? Much of the two-day event strained us beyond the literary context that brings many of us to the Folger Shakespeare Library. Liza’s wonderfully suggestive reading of Chapman’s stoic poetics and physics suggested ways that the literary speaks to the sciences, social sciences, and more public and political discourses.

Slimy Agitation Chris Pastore’s bottom-up history of the ocean and its “thousand thousand slimy things” provided the perfect ending to our gathering because its vision of a material, foamy, slimy experience-filled ocean allowed us to see, or perhaps better to feel, the world into which we were heading. I’ve been thinking about jellyfish for a long time, and what it will be like as an ocean swimmer to learn to live with their slimy sting. Chris didn’t make that prospect seem more comfortable — but he did suggest that slime is less the exception than the rule in ocean history.

Closing Roundtable: Interlopers and invitations

I had probably too much to say at the closing roundtable, as perhaps this too-long blog post shows that I still have too much to say. But the thing I want to remember now was about interlopers and invitations.

Several people, mostly humanists who don’t identify as ecocritics, but I think also the scientists and non-Folger natives, spoke about the challenge of feeling like an interloper among Shakespeareans. I understand that feeling, and I often feel it too. But since I was the one who issued the #creatingnature invitations, I want to re-emphasize Lindy’s wisdom: “Everybody is invited all the time.” If you think about that phrase, it’s a challenge both to the invited and the hosts. All the time!

We feel like interlopers. We can, in fact, interlope, moving into conversations in which we’re not expected.

But to build a new infrastructure adequate to the Nature our culture has created needs all of us. Everybody’s infrastructure all the time. That’s what we need, and we need it now.

Looking forward to the next gatherings, wherever they will be!