The most brilliant, painful, and astounding performance was the last — but I’ll take the kings in chronological order. Six of them , lined up in a long row.

, lined up in a long row.

Henry IV

The dying old man laid out prone on the white hospital bed dropped wisdom on the son who’d already begun playing with the English crown. There’s an easy way toavoid trouble at home, the old man advised: “Busy giddy minds with foreign quarrels.”

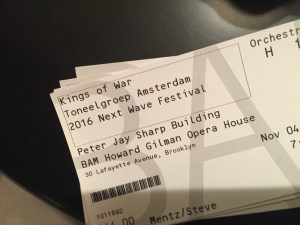

So started four-and-a-half hours of Toneelgroep Amsterdam’s brilliant and searing Kings of War, directed by Ivo van Hove, which is spending the pre-election weekend at the BAM opera house. A master class in domination, violence, and strategy, it was just the thing to redirect political jitters for a few hours on Friday night. Politics as bloodsport and play, not exactly as Shakespeare wrote it — the performance was in Dutch with supertitles, and stripping down five plays into one night required aggressive cuts — but certainly as Machiavelli understood it.

Henry V

The first crowned monarch — all the kings were crowned on the same red carpet, followed by the same single file line, stretching out to the edge of the stage — started quietly. Ramsey Nasr played Henry V with no visible traces of Prince Hal, and he invaded France without any leavening from Welsh or Scottish captains, fiery Pistol, or tears at Sir John’s death. Playing against the patriotic swellings we remember from Olivier’s and Branaugh’s films, this Henry V was frightening because he was just a little bit opaque, not quite accessible. Thinking back over the long arc of the full production, I see Henry V as a tactical serpent, exporting to fertile France the destructive forces that would bloody England during successive reigns. Watching his army’s march through Harfleur to Agincourt as a preface to Rose War rather than the culmination of Hal’s journey makes the wastrel-king harder to read. In the sort of outrageous theatrical coup that Toneelgroep has been specializing in for years — here’s my gushing review of their Roman Tragedies, which I saw at BAM in 2012 — the king spoke the Crispin’s day speech as voice-over on a bare stage. The band of brothers, with its fantasy of an organic (masculine) political body unified through royal rhetoric, was nowhere to be seen. Perhaps it doesn’t really exist?

The stage was set in the first half of the production (a touch of H4, H5 and the first two parts of H6) to resemble Churchill’s War Rooms, now a museum in London, with maps, desks, and a single bed (in which Henry VI would sleep after kneeling in prayer). The great innovation of the staging, however, was several backstage hallways, which were included in the action via stedicam footage that was projected on a massive central video screen. The screen showed some backstage murders, conspiracies, and even, during a memorable speech in which King Henry VI indulges in a pastoral metaphor, a flock of sheep (or goats, maybe?). With the exception of the livestock, most or all of the filmed action was live, but it was only visible to us via video feed. The result was as seamless an intermingling of live and filmed action as I’ve even seen, making even the Wooster Group‘s pyrotechnics appear a bit labored. Another patterned staging showed figures of authority — York and Richard III, especially — seated with their backs to the audience but with their faces shown in close up on the big screen. The combination of contempt for and intimacy with the masses was potent and disturbing.

This staging of Henry V moved without a pause from his securing the hand of Princess Katherine to the conquering monarch’s funeral, which opens Part 1 of Henry VI. This staging of wooing scene, often a semi-comic break from the relentless battles, showed the king’s emotional neediness more than his mastery. In a sharp inversion of common practice, the scene suggested that Katherine understood the king’s English but he cannot fully decipher her French. His sometimes comic lines about being a soldier who cannot speak love-verses built to his petulant fists pounding on the table in frustration. The princess, and the off-stage negotiators of the Anglo-French treaty, rescued Henry — but the sense of not-fully-visible violence, like the rapine and pillaging the king had threatened but not visited on Harfluer, lingered after the conqueror passed.

Henry VI

Eelco Smits’s boyish Henry VI looked out of place in his pajamas among the senior military men dressed in suits. Crowned at six months old and never quite growing into his father’s bloody shoes, this Henry brought the play’s action back to England and civil war. All Shakespeare’s French scenes, except Suffolk’s wooing of Margaret, were cut, and to the list of missing figures these plays added Joan of Arc, Jack Cade, and several others. The cabinet room now overflowed with rivalries: the Cardinal and York and Suffolk plotting against Henry’s uncle, Duke Humphrey of Gloucester, whose losing hand was played with brilliant frustration by Aus Greidanus, Jr., who would later play Buckingham in Richard III. But the blazing star of the Henry VI plays, and one of the two incandescent performances of the evening, was Janni Goslinga as Queen Margaret of Anjou.

Margaret, “the she-wolf of France,” dominated the Henry VI plays, especially in a production like this one that cuts Joan of Arc and Jack Cade and minimized Warwick the Kingmaker. Goslinga’s performance ratcheted up the human intensity of the political intrigue, which shifted from Henry V’s war-strategy to a complex multi-party civil war. King Henry VI’s famous piety saw him kneeling in pajamas at his cot while the senior administrators continued their business meeting, but this abdication frustrated Margaret’s ambition for herself and her husband. She burst into rage when Henry VI disinherited their son in order to prevent his rival, the Duke of York, from pushing him off the throne. While the production skipped most of the final stages of the civil war, including almost all of Henry VI, Part 3, which includes Margaret’s great despairing speech — “Say you can swim; alas, tis but a while” — but she dominated the middle section of the performance.

Edward IV

In a nod toward clarity, Kings of War crowned the Duke of York, rather than his son, who was also named Edward. The key scene featured York with seated at a conference table with his back to us, holding aloft a lit cigarette in his right hand. The video screen displayed his impassive face. We watched the smoke curl up as the Duke let his silence negotiate with an increasingly frantic King Henry VI. At the end, York was named heir, Margaret raged against an impotent Henry, and the Lancastran forces were routed. In Shakespeare’s dramatic cycle, completing project takes several more battles and campaigns — but York’s stillness and the implacable control of Bart Sleggers’s performance stood in nicely for all that violence. When the curtain at last came down after two and a half hours (only one interval!), the white rose of York was firmly in command, though the arrival of a certain son, Richard Duke of Gloucester, whose late self-atomizing speeches were almost all Toneelgroep kept of Henry VI, Part 3, promised futures troubles.

Richard III

Hans Kesting, who I’d previously seen play Antony in Toneelgroep’s Roman Tragedies, gave the part of Richard III a sinuous intensity that I don’t think I’ve ever seen equalled on stage before. Without any elaborate physical hijinks or props, except a wine-colored stain under one eye, he carried Richard’s dark ambition and restlessness through his body. He threatened just by standing still: I’m not sure that I’ve ever seen a more ominous stage moment than watching him stand on one side of the stage, staring at his reflection in a full-length mirror, while other characters pretended that they controlled the kingdom. I’ve seen Ian McKellen and Kevin Spacey give strong live performances of King Richard — but Kesting roared over all of them. As my buddy Erik said after the curtain, “I guess I don’t need to see Richard III ever again.”

It’s hard to describe the impact of seeing Kesting’s Richard on stage. I think it had something to do with the way he held his body, and also something to do with the way I’d been holding my body for the past 3 hours when he finally arrived on stage. Kesting walked gingerly, as if he were a coiled spring, with his hips slightly forward and arms back, enough to disturb but not enough to be a caricature. At one point his cascaded into full ridiculousness, wearing the crown he’d not yet claimed, draping a rug over his shoulders, and running around the stage in a parody of the humpbacked king. Most of the time he was just alien enough to disturb but not disrupt.

I also think the way the show made us wait for Richard made a difference. By the time he appeared, we’d been sitting still for over two and a half hours, and the late arrival of the man we knew would be the last titular king in the sequence focused our attention. If Henry V, conqueror of France, was understated and his play oddly calm, Richard III arrived to upstage him — though of course the final turn to Richmond, the future Henry VII, also returned Ramsey Nasr, who’d played Henry V, to center stage.

A few moments of Kesting’s Richard particularly linger. When he was sure he was about to be crowned, he sat at the war room table in front of three brightly colored hotline phones. He lifted the red phone, drawls into in in a fake American accent: “Hallo?…Barack?!” Guffawing, full of himself, he next grabbed the green phone and spoke in German to Angela Merkel. To the blue phone he barked at Putin in Russian, then mocked the Russian leader as a “pussy” after he hung up.

Especially after reading the harrowing reporting from Trump’s gold-plated plane in this morning’s Times, I’ve been mulling how Kesting’s Richard combined ruthless domination with near-absolute neediness. The seduction of Lady Anne, about which Richard crowed when she left the stage, played itself out through utter desperation and need. When he bared his breast and offered her the knife, his brutal control operated through his urgent need to be at the center, the most hated and the most loved, the only one who matters:

Lo here I lend thee this sharp-pointed sword,

Which if thou please to hide in this true breast,

And let the soul forth that adoreth thee,

I lay it naked to thy deadly stroke.

No wonder Anne couldn’t kill him. Who could strike in the face of so much need?

Richard’s successful wooing of Anne to be his wife gets inverse-mirrored late in the play by his failure to convince Elizabeth to woo her daughter to be his next bride (4.4). Chris Nietvelt, who had previously played the French herald Montjoy, staged Elizabeth as Richard’s match, in a way that Anne and even Margaret had not been. After she left the stage, having not agreed to his proposed match for her daughter, Richard gave the Brooklyn theater one last crowd-pleasing ad lib: “nasty woman.”

The night before the battle showed Richard seated in the position of power on a bare stage with his back to us, staring at his own massive image on the video screen. Slowly, the features blurred to reveal, superimposed, the faces of his victims: Edward, Henry VI, Clarence, the two young princes, Lady Anne. Their presences drove the king mad, and as the screen faded to blood red he galloped around the stage bellowing, “a horse, a horse, My kingdom for a horse!” The famous line reimagined itself as pure physical need, desire for a stronger and more durable body, a vehicle for Richard’s boundless ambition and drive. We never saw him die: as he galloped horseless around the red stage, the video curtain pulled up to reveal the entire cast, now dressed as supporters of Richmond’s invading army, with Richmond himself at the head. Richard snaked through the crowd and vanished into the backstage hallway, not to return until the ovation.

Henry VII

What did the new king mean? The cycle closed with another Henry and another coronation for Ramsey Nasr, who had started us off as Henry V. The circular turning and absence of the tyrant’s body suggested that not all evils have been firmly banished. “The dog is dead,” said Richmond, as he prepared to marry to white rose to the red. Would that all political divisions were so easily sutured.

Leave a Reply